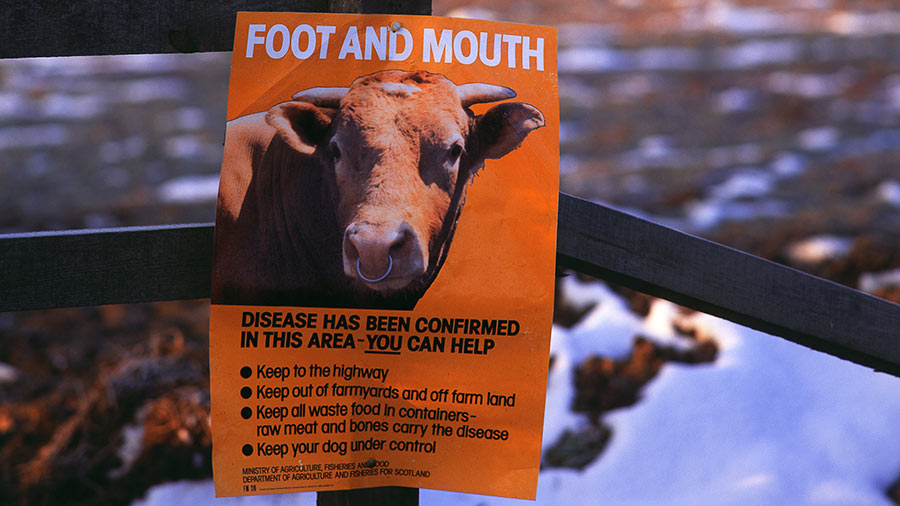

Analysis: How good are foot-and-mouth controls 20 years on?

© Science Library

© Science Library It is 20 years since foot-and-mouth caused a crisis in British farming as it swept through the countryside. Millions of livestock were slaughtered, leaving farms devastated. We ask, two decades on, could it happen again?

Dr Craig Kirby, who works as a veterinary adviser to the Association of Independent Meat Suppliers (Aims), says the outbreak exposed several risk areas in the control of animal disease, including waste feeding of pigs, and enforcement of the system in place for recording livestock movements.

He was the vet on duty at the Cheale Meats abattoir in Essex when a lairage worker called him over to inspect a pig with blisters on its feet.

Dr Kirby’s subsequent phone call to the then Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food marked the beginning of a chain of events that led to worldwide sanctions on all pig, sheep and cattle exports, a national livestock movement ban and massive financial losses for agriculture and rural tourism.

See also: Farming rises from the ashes

At the time, the modelling work for transmission was based on the assumption that all movements were conducted legally, which was “plainly naïve” according to Norman Bagley, head of policy at Aims.

Movement controls

Even though there are now new systems in place to control movements, Mr Bagley suggests many are still unrecorded. “It only takes a relatively small amount of illegal movements to screw everything up,” he points out.

So, is Defra in a significantly better place to control an outbreak 20 years on?

“It is questionable,” says Mr Bagley. “Surveillance is still poor, very few farmers are caught and prosecuted for illegal movements.”

But Defra insists otherwise. It monitors the international disease situation closely and in November 2011 published its foot and mouth disease control strategy.

Prior to this, it says its processes were shown to work well during the 2007 foot-and-mouth outbreak, limiting infection to 81 premises compared to more than 2,000 in 2001.

“This outbreak was also managed at the same time as outbreaks of avian influenza and bluetongue,’’ says a Defra spokesperson.

Steps are also being taken to improve recording of livestock movements – a new single, multispecies livestock movement service, which will replace outdated existing services, is due to go live next year.

The Livestock Information Service will completely replace the three legacy services that trace cattle, pigs and sheep, goats and deer.

This, Defra says, will enable more-effective livestock disease management and control nationally, regionally and within herds and flocks. And it will incorporate accurate disease forecasting and data modelling, together with “proportionate, targeted enforcement and inspections”.

Mr Bagley sees this as a step in the right direction. “Since BSE and foot-and-mouth, there have been various attempts to make the controls we have in place better, but there have been huge holes in the system.”

Import threats

Yet the UK is under constant threat of a disease incursion from overseas.

The disease exists in many other countries. Foot-and-mouth is estimated to circulate in livestock in Africa, the Middle East and Asia, and in some parts of South America.

The EU Food and Veterinary Office (FVO) conducts regular and rigorous inspections in countries that the EU trades with.

But the Farmers’ Union of Wales (FUW) had raised concerns about the slow actions taken by the EU Commission when failings were identified by the FVO’s thorough investigations.

For example, when it found many anomalies in Brazil in the first decade of the 2000s, the commission took no action until the FUW, the Irish Creamery Milk Suppliers Association (ICMSA) and others complained in a joint submission to the EU Ombudsman.

The commission then took action and restricted the number of Brazilian farms permitted to export to the EU to a small handful of compliant businesses.

Post-Brexit worries

Now that the UK has left the EU, the FUW’s concern has shifted to a UK-specific policy – or rather the perceived absence of one.

“What inspectors and systems will the UK have to ensure foreign compliance with trade agreement rules aimed at protecting us?” asks an FUW spokesman.

The union suggests that nothing anywhere near as substantial, rigorous or robust is being proposed within trade deals.

In recent months, it has repeatedly raised this with the UK government. “There is all this spin about trade deals with different non-EU countries, but a deafening silence about how we will inspect other countries’ systems of traceability to make sure they comply with our standards,” says the FUW.

“It’s even suggested that we should rely on something like self-certification by countries with which we strike deals.”

That, says the FUW, should be a major concern around the threat from exotic diseases that could devastate the UK’s livestock industry.

Case study: Baden and Netty Rees, Coed Owen Farm, Brecon

In the panic that swept the country back in February 2001, millions of healthy animals were killed, including Baden and Netty Rees’ entire hefted hill flock of 2,800 sheep.

The pain of their loss was felt keenly because it was unlikely that any of the animals had the disease.

“When the ministry vets inspected our flock they told us they found a few ewes with lesions, but the results came back inconclusive,” says Mrs Rees. “We understood the cull of our flock was contiguous to stop the disease spreading further down the valley.”

The Rees’ had been farming at Coed Owen Farm near Brecon for six years. At the time their three children, Molly, Jack and George were all under nine.

“We had a lot of farming friends, especially on the hill adjoining us, whose families had been there for generations,” says Mrs Rees.

“We witnessed old farmers cry at the loss of their livestock. The older generation of Beacons farmers who were born and bred here, and had hefted generations of sheep, were angry and very sad.”

Rebuilding

The Rees’ ploughed the compensation they received into restocking, but it took them 12 months to make the decision to continue farming.

“We didn’t know whether to jack it all in and walk away, but we decided to give it another go,” says Mrs Rees. “We were sufficiently compensated, which helped us to secure our future at Coed Owen and restock the hill flock on the Brecon Beacons.”

Did the crisis bring the rural community together? “Yes it did. We knew many farmers who didn’t lose their livestock to foot-and-mouth, but struggled financially as it was near impossible to trade normally,” says Mrs Rees.

The family rebuilt their flock and today run 2,200 breeding ewes and a herd of suckler cows. Molly and Jack are now farming with their parents.

Mrs Rees says there are no guarantees that history won’t repeat itself, but believes that governments would respond differently if foot and mouth did reappear, by only culling on positive results.

“It seemed such a waste of life, to destroy so many healthy animals. Was there any need to do that?”

Case study: Gareth Davies, Cwmgwilym, Brecon

The memory is one that haunts Gareth Davies and his family to this day. Lorries lined up in the farmyard at Cwmgwilym, Brecon, as marksmen shot their livestock.

“The marksmen were very considerate. The animals stood quietly, chewing their cud and they just fell as they were shot,” Mr Davies recalls.

“It was a very difficult and upsetting time emotionally, but it must have been even harder for the dairymen who knew each and every cow more closely.”

The Davies family lost 25% of their sheep and cattle, including an entire flock of pedigree Rouge sheep, which they had established over a period of 15 years.

There was no evidence of foot-and-mouth in the livestock, but they fell victim to contiguous culling – some animals on off-lying land had to be slaughtered on welfare grounds.

The business steadily recovered and rebuilt livestock numbers, emerging from the epidemic stronger and more efficient.

“The government compensation payments were fair, enabling us to restock. We had the money to go out and buy replacements,” Mr Davies recalls.

New challenge

But a disease of a different kind has since brought further pain.

A bovine TB inconclusive reactor (IR) halted the farm’s suckler herd dispersal sale in August 2020 and delayed plans to restructure the business to make it more viable as the Basic Payment Scheme is phased out.

“We had built up our suckler herd over a lifetime and to be told two weeks before the sale that we had an IR was devastating,” says Mr Davies.

The herd has since gone clear and he has sold some of those cattle, but it was a worrying reminder of how disease can wreak havoc on farming operations and future plans.

“I question whether the Welsh government fully understands the emotional and financial impact that TB movement restrictions have on the individual farming businesses,” Mr Davies adds.