Foot-and-mouth 10 years on: Farming rises from the ashes

A harrowing crisis that wrought despair and devastation. Ten years ago Cumbria farmers found themselves in the midst of the maelstrom of the foot-and-mouth epidemic as mass livestock burials and plumes of putrid black smoke from smouldering pyres began dismembering the industry of which they were so intensely proud.

Cattle, sheep and pigs on almost 3000 Cumbria farms were slaughtered during the F&M outbreak of 2001.

But fortitude and resilience lie deep within the Cumbria psyche. Despite the trauma wreaked by the impact of the disease and the emotional body blow that left the county’s farming community bereft of its stock and its livelihood, Cumbria’s agriculture has recovered. Today it is even more vibrant than it was a decade ago – despite having to cope with the pressures of an increasingly volatile livestock sector.

About £90m of F&M compensation was paid to Cumbria’s farmers, but no amount of financial recompense could ever replace the generations of prized stock breeding and hallowed genetics that were obliterated during the outbreak – particularly among flocks of Swaledale sheep and pedigree cattle.

Cynics may have their own opinion, but when the cheques came in few farmers in Cumbria decided to take the money and run. Compensation was re-invested in farms across the county to strengthen and expand their infrastructure, but a lasting recovery from a crisis of this magnitude had to come from a vigorous and radical re-think – and it did.

THRIVING MARTS

Talk to any of the county’s livestock auctioneers, many of whom were in the front-line of pre-slaughter stock valuations, and they will admit they feared the disease would trigger the end of live selling and lead to the closure of all livestock auction marts. Thankfully that knee-jerk reaction to the new buzzword “biosecurity” never happened. Cumbria still supports a thriving network of livestock markets.

But even though many marts remain at the heart of stock selling in the deeply traditional hill farming regions of the county, the momentous events of 2001 were set to change the unchangeable.

No other man understands the traditions of Swaledale sheep breeding and selling more than auctioneer Stuart Bell of Harrison and Hetherington’s mart at Kirkby Stephen. Mr Bell, who was involved in more than 400 flock and herd valuations during the outbreak, said the Cumbria sheep industry has changed “dramatically” over the past decade.

“Before F&M 80% of the prime sheep we sold were hill breeds – predominantly Swaledales and Rough Fells. Now almost 60% will be sired by Texel and Beltex. Environmental schemes played a part through their destocking of the fells, but F&M sparked a much wider change in attitudes.

“Instead of breeding Mules out of Swaledales, more hill farms started keeping Mules to produce top quality prime lambs. It’s been a significant about turn,” said Mr Bell.

Of those who used the opportunity to instigate an era of improvement were brothers Mark and Andrew Brown of Asby Hall, Great Asby, near Appleby.

The Brown family’s 800 Swaledale ewes and 100 suckler cows were slaughtered during the outbreak: “We did nothing for a while because it was such a shock to lose everything. But we were determined to try and come back stronger and better and look at how we could improve,” said Mark.

The family stayed true to their hill farming traditions but set new targets. It has certainly paid off and has seen them achieve a wide reputation for their stock. Last autumn they took the coveted championships at two of the main sales held by the North of England Mule Association selling one of their wining pens of 10 lambs at £500 each.

Many of the UK’s 62 pig producers who fed swill were based in the north at the time of the outbreak but by May 2001 all had been shut down. None received any compensation.

Lynda Davies, co-ordinator of the Swill Feeders Group, has continued to press the government to recognise the massive financial losses these pig producers suffered.

“Their businesses were wiped out overnight despite the fact there was never any solid evidence that swill feeding was implicated in the outbreak. It is very unfair that these producers were singled out and left without any compensation to re-invest in a new business,” said Ms Davies.

But in the after-shock of F&M many farming families found themselves with time to re-evaluate their lives and to re-consider their futures. It was a rare, albeit enforced, opportunity for reflection. What had always been was no more. Now there was an opportunity to re-align businesses and even to re-invest.

Cumbria is now the UK’s largest milk-producing county and many dairy farms used their compensation to finance herd expansion. It is ironic that while the current pressures of the dairy sector are being felt no more strongly than in Cumbria, the post F&M period of re-investment has at least given the county’s milk sector a stronger on-farm infrastructure to help it cope.

Andrew Humphries is now retired from his post as assistant director of the county’s Newton Rigg College at Penrith. But he was a member of the F&M enquiry panel and one of many volunteers who manned the county’s telephone helpline during the darkest days of the outbreak.

FIGHT BACK

“I took about 3000 calls during that time. It was a desperately sad period for everyone who lived and worked in the county – and not just those directly involved in farming. But despite the distress the disease inflicted, Cumbria fought back. Everyone wanted to get farming back on its feet as quickly as possible.”

Travel around the county today and it is hard to imagine what happened here a decade ago. Dig deeper and there have undoubtedly been subtle social changes.

While there was certainly no exodus from farming per se, the crisis spawned an independence among many farmers’ sons who have since created a county better served than most with a proliferation of contracting businesses.

Cumbria certainly did not want to achieve notoriety on the back of the most serious disease outbreak in the history of UK farming. But with a plethora of support and advisory schemes put in place to aid its financial recovery, the huge variety of regional food produced in the county has now achieved nationwide acclaim.

The promotion of the generic “Cumbria” brand has enabled many successful food producers to develop their markets over the past decade. The turmoil of foot-and-mouth is now very much dead and buried.

A lasting legacy – a decade after foot-and-mouth

Ten years ago, the only farmers at Hatherleigh livestock market in Devon would soon be the statue of three shepherds minding their sheep at the market entrance.

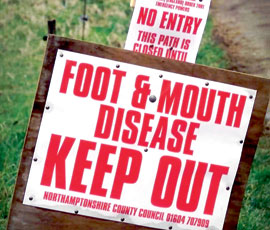

Like the rest of the country, this small market town was on the brink of Britain’s worst ever foot-and-mouth outbreak. The countryside would be closed, livelihoods lost and more than 10m livestock slaughtered.

Today, life in Hatherleigh has long since returned to normal. But the legacy of F&M lingers. Almost everyone in this close-knit community was affected. Many are understandably reluctant to talk about it.