Machinery Milestones: UK tractor-building revolution failure

Agricultural and General Engineers (AGE) was formed in 1919 to help Britain’s tractor and machinery industry compete against the big American manufacturers, but it ended up putting some of its members out of business.

AGE was formed when Britain’s agricultural engineering industry was facing major challenges. Britain had been the world leader in the agricultural steam power success story that began in the 1840s, with British companies introducing most of the technical advances and dominating export markets worldwide.

However, by the end of the 1914-18 war tractors with combustion engines were getting more popular and demand for steam power was fading rapidly.

Petrol tractors arrived on US farms in 1889 and in Britain from 1896, but they attracted little interest at first because of reliability problems caused by the early fuel and ignition systems.

Tractor popularity increased gradually during the early 1900s, but it was the war that brought a big surge in tractor sales and saw to the demise of agricultural steam power.

See also: Machinery Milestones: Electric tractor power

The challenges of war

One of the reasons for the wartime increase in tractor numbers, particularly in the US, Canada and the UK, was the need to boost farming efficiency to compensate for large numbers of men and horses leaving for the battlefields of Europe.

Saunderson, based near Bedford, was Britain’s only large-scale tractor maker at the time of the First World War

An additional factor in Britain was the success of German U-Boat attacks on ships bringing in food supplies, and the government responded with an emergency campaign to increase home-grown food production.

The campaign required thousands of additional tractors, but the Bedfordshire-based Saunderson company was Britain’s only established tractor manufacturer with the capacity to supply significant numbers.

As a result, the bulk of new tractors came from fast-expanding American production lines, plus a small number from Canada.

While imported tractors were helping to produce Britain’s food during the war, most of the British farm equipment manufacturers were busy with contracts to make military equipment.

They made a significant contribution to the war effort, but the contracts dried up when the fighting stopped in 1918, leaving many of the companies with a challenging future.

The steam equipment specialists faced the biggest problems as UK and export demand faded, but there was increasing competition for general machinery.

Assembling AGE

AGE was formed in 1919 by five previously independent companies. More joined the following year to bring the total to 14.

Five of them were steam engine makers, including Garrett and Burrell – two of the leading agricultural steam power specialists – and Aveling & Porter, the biggest steamroller manufacturer.

Other member companies covered a wide range of mainly agricultural products and included barn machinery specialist Bentalls; leading cultivation machinery builder J&F Howard; LR Knapp, which made seed drills; and Blackstone, a petrol engine specialist that also made farm machinery.

The 1919 Blackstone was the first AGE tractor

Most of the companies were family-controlled, and to join the new organisation the owners exchanged their own company shares for the equivalent value in AGE shares.

This left AGE owning 100% of 13 member businesses. The exception was Peter Brotherhood, a general engineering company in which the AGE shareholding was 70%. Membership qualified each company to a seat on the AGE board and a share in any AGE profits.

A potential benefit of being part of AGE was increased bargaining power through bulk buying of components and raw materials, and establishing a purchasing department was one of the new company’s first priorities.

It offered the possibility of substantial cost savings, but the results are said to have been disappointing because some member companies preferred to continue buying from their previous suppliers.

This was one of several examples of AGE directors, who had previously run their own independent companies, finding it difficult to work as members of a team.

There were reports of angry board meetings when past rivalries came to the surface. There were also suggestions that some applications to join AGE were rejected for personal reasons rather than commercial logic.

An important decision for AGE was selecting a headquarters location, and the final choice was a large and prestigious office building near the Strand in central London.

It was an impressive home for an organisation with ambitious plans for the future, but instead it became a financial millstone as the expansion plans failed to materialise.

Post-war challenges

One of the post-war problems for AGE – and for Britain’s agricultural equipment manufacturers generally – was lack of success in the tractor market while demand for agricultural steam power continued to shrink.

Tractors were a potential growth opportunity that attracted a number of UK companies to move into the market for the first time, but none achieved long-term success.

Saunderson, Britain’s only large-scale tractor manufacturer during the war, was one of many that failed to survive and production ended in about 1925.

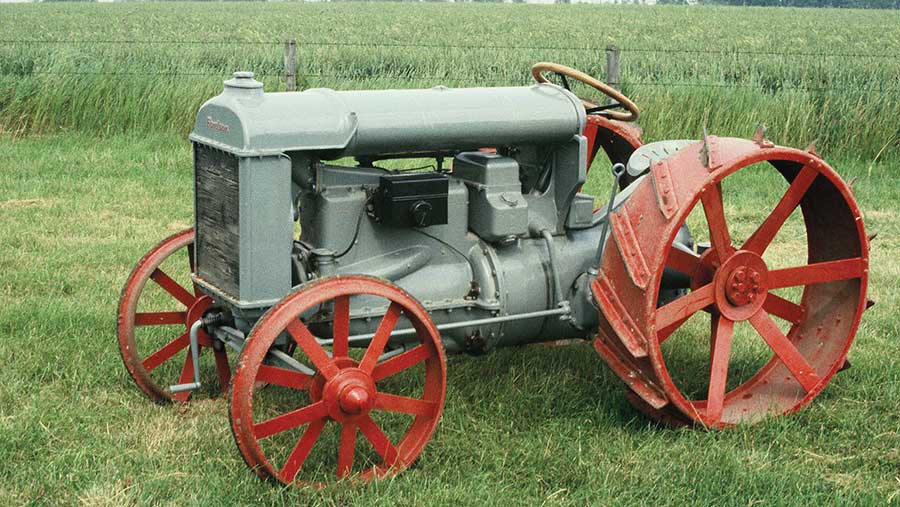

The Fordson, designed for mass production, had an unbeatable price advantage at £120 in 1922

Meanwhile the government’s food production campaign provided valuable publicity for the imported tractors, as many of them travelled from farm to farm providing a contracting service for jobs such as ploughing.

This helped to establish leading US makes such as Allis-Chalmers, Case, Fordson and International Harvester, as well as Massey-Harris from Canada.

The American arrivals also included a large number of Waterloo Boy tractors – the name was changed to Overtime in the UK – which were the forerunners of the John Deere tractor range after Deere and Co bought the Waterloo company in 1918.

One of the biggest challenges for AGE and other British manufacturers was price competition, particularly from Ford, which had designed the Fordson for mass production.

In 1922, the UK list price for a 20hp Fordson with a three-speed gearbox was £120, while the 25hp Austin tractor with two forward speeds had recently been reduced from £360 to £300, and a 25hp tracklayer made by the AGE-owned Blackstone was listed at £420.

Price comparison is always a factor in the farm machinery market, but its importance increased during the 1920s as the farming industry shared the serious financial downturn affecting developed countries worldwide.

The economic situation was a significant factor in the problems faced by AGE.

AGE tractors

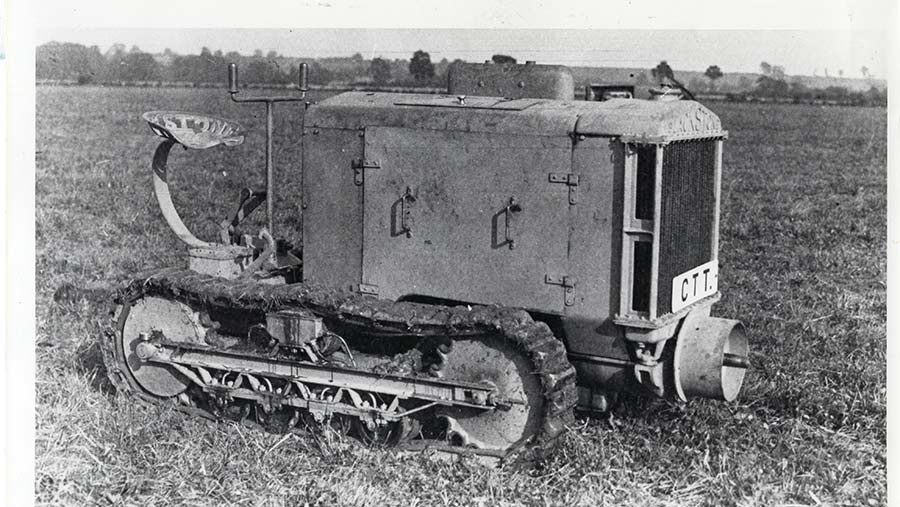

AGE tractor production started with the Blackstone tracklayer announced in 1919. An unusual design feature was the three-cylinder engine using paraffin for starting and running, with a compressed air starting system.

There were few sales, partly because of the high price, and its prospects were not helped by the official report from 1922 tractor trials in Scotland.

The Blackstone was described as not suitable for Scottish farming conditions, but the report failed to explain why.

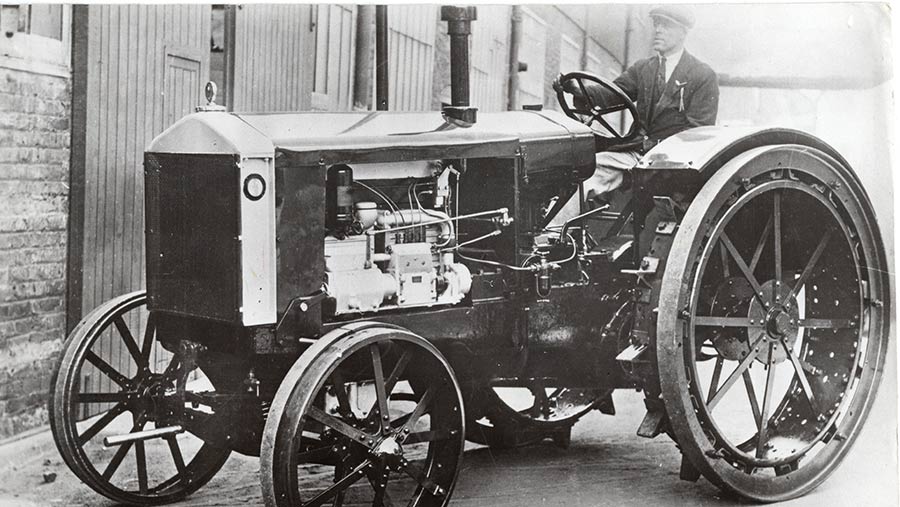

The next AGE tractor was the Peterbro, which arrived in 1920 from the Peterborough-based Peter Brotherhood company.

This was another up-market model, with 30hp available from a petrol/paraffin engine provided by the leading designer Harry Ricardo. Again there were few sales, and the addition of a tracklaying version in 1928 failed to boost demand.

The Peterbro, with a relatively powerful 30hp engine, failed to attract significant sales

The third and final tractor from AGE was made by the Suffolk-based Garrett, which was adjusting to the loss of its immensely successful steam engine business. The tractor was announced in 1929 with two high-speed, four-cylinder diesel engine options.

The Blackstone engine produced 26hp and the Aveling & Porter engine 38hp. Multi-cylinder diesel power is standard equipment on today’s tractors, but was almost unknown in the 1920s, and the decision to use this type of engine in the Garrett tractor was far-sighted.

Both versions competed in the 1930 World Tractor Trials in Oxfordshire, where they won official praise for low fuel costs, and the Blackstone engine also attracted favourable comments for its smooth running.

The Aveling & Porter-powered Garrett won a silver medal at the 1931 Royal Show, where the judges’ official report said it was a “remarkably fine piece of English engineering workmanship” and “a pleasure to an engineer to look at”.

The Garrett was probably the most advanced diesel tractor in the world at that time, but only about 15 were sold, including two of the later tracklayer versions.

Price remained a key barrier to sales – in 1930 the 26hp Blackstone-powered version was listed at £500, compared with £248 for the 27hp Case Model C and £156 for a Fordson.

In spite of advanced engine technology and official praise, the Garrett’s price premium was too great at a time when farmers were facing shrinking profit margins and the general economic situation seemed bleak.

The end of AGE

Although the Garrett tractor was not a commercial success, it achieved at least one positive outcome. The AGE company ceased trading in 1932, but two Aveling & Porter executives were so convinced about the advantages of diesel power that they decided to form their own company.

The Garrett, with its choice of four-cylinder diesels, was cutting edge in its day

One was Frank Perkins, who gave his name to the Peterborough-based company that later helped establish Britain as a world leader in agricultural, industrial and marine engines.

Probably the biggest problem for the Garrett tractor was AGE’s shaky financial situation. After many loss-making years, the company was reaching crisis point and, in 1932, the receiver took over.

By this stage the company had already lost some of its members, including Charles Burrell, which had ceased trading in 1928 because of the collapse in steam engine sales, and in 1930 AGE had sold its 70% shareholding in Peter Brotherhood.

The remaining AGE members were sold by the receiver in 1932, generally at low prices because agricultural engineering in the 1930s was not a popular investment choice.

Some of the former AGE member companies returned to their previous family ownership, but generally it was a difficult time for Britain’s agricultural engineering industry and continuing competitive and economic pressures brought more casualties.

When the Second World War started in 1939, more imported tractors were needed to help boost Britain’s food production, but the biggest supplier was Fordson, by then being produced at its factory in Dagenham, Essex.