Machinery Milestones: Electric tractor power

Electric tractors may have achieved little commercial success during the past 120 years, but plenty of companies and academic institutions have tried to end diesel’s domination, and things look set to finally change as environmental pressures increase.

Probably the first attempt to use electricity to power field equipment was in 1894, when the Zimmermann company in Germany demonstrated its self-propelled electric ploughs.

There were two versions, one with a 10hp motor turning two furrows and a four-furrow version that used a 16hp motor.

The 16hp plough received its electricity through an overhead cable from a mains supply, but the 10hp version was linked to a steam-powered generator on the headland.

The electric motor on both ploughs powered spur gears that pulled the plough by meshing with the links in a chain stretched across the field and anchored at both ends.

After crossing the field, the plough plus the chain and the anchor points had to be moved the correct distance, ready for the return journey, and another frequent task was moving the supports that carried the power supply cable above the soil surface and out of contact with the plough bodies.

Apart from reducing the workload for the farm horses, the Zimmermann ploughing system seems to have offered few benefits and it is unlikely any were sold. But the publicity may have prompted a French farmer named Felix Prat to use electric power for ploughing in 1895.

A water mill on his farm was converted to produce electricity to operate a home-made tractor and, as well as powering the tractor wheels, the electric motor drove a winding drum pulling a rope attached to a plough or cultivator to and fro across the field while the tractor remained on the headland.

See also: Machinery milestones: driverless tractors

Commercial success

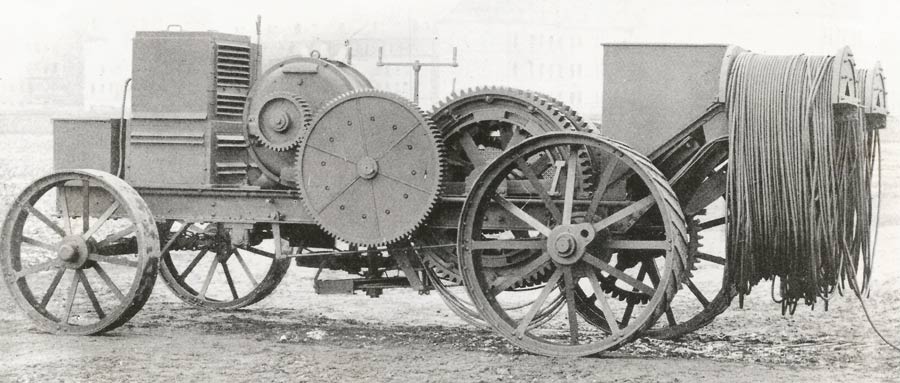

Small-scale commercial success came in about 1900 when Brutschke electric tractors were used for ploughing in Germany.

The tractors were used on farms near a sugar beet processing factory that had installed a generator to supply electricity for handling and processing the beet, but for much of the year there was surplus electricity available that could be supplied through overhead power lines to farms close to the factory.

In the early 1900s Brutschke tractors used surplus electric power from a sugar beet processing factory in Germany

A report published in 1902 stated that several of the larger farms were using the factory’s “off-peak” electricity to power the 220V motor on Brutschke tractors.

Like the French example, the tractor stayed on the headland while a winding drum operated a rope or cable system pulling an implement across the field.

Farmers using the electric tractors claimed the ploughing cost was cheaper than using a steam-powered cable system.

Scotland’s contribution to electric tractor history began in 1925, when Major Andrew McDowall, an East Lothian landowner, built an experimental tractor powered by a 12.5hp motor.

The tractor was based on a three-wheeled chassis, with ploughs attached to the front and rear working alternately as the tractor travelled backwards and forwards.

Power was supplied through a cable plugged into a power point that could be repositioned as the ploughing progressed, allowing the tractor to travel about 400m in each direction.

Scotland’s first electric tractor pictured without its front and rear plough attachments

Ploughing with electric power was half the cost of using an ordinary tractor, Major McDowall claimed, but his request for government finance to enable him to carry out further research met a polite, but firm, refusal.

Russian progress

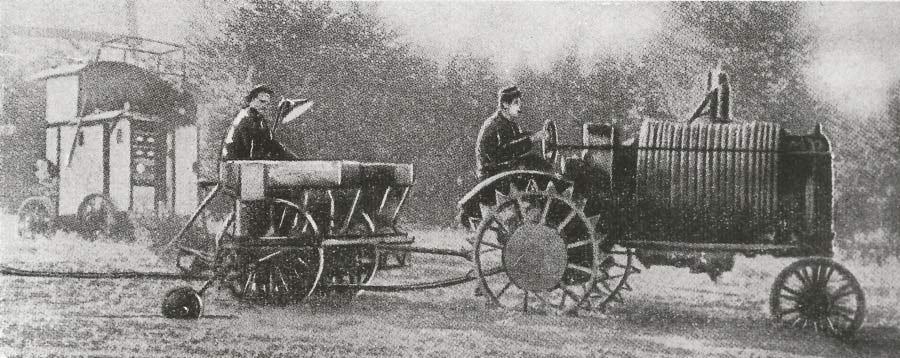

Electric tractor development moved to Russia during the 1930s and 1940s, but few details are available.

In 1950 the Russian government department providing overseas publicity for the country’s achievements announced that electric tractors had become a big success.

From 1945 to 1949, the number of electric tractors on Russian farms increased by 300%, said the report, and they worked so well that a further large-scale increase had been approved.

Photographs in the report showed tracklayer and wheeled versions at work, both linked by cable to an electricity supply.

Russia’s electric tractors included this wheeled model with a trailing power supply cable

Russia’s electric tractor programme may have been less ambitious than the publicity suggested and, more recently, a senior agricultural official from Russia said the programme had been abandoned in the early 1950s due to technical problems.

Only a small number of tractors had been made, and they were just a brief episode in the history of Russian power farming, he explained.

One of the big problems faced by the electric tractor pioneers was dealing with the power supply cable, and this may have been one of the reasons for the failure of the Russian programme.

There are obvious risks of wear and tear if the cable is dragged across the soil surface, and it could become tangled with the tractor wheels or the implement during a headland turn.

Electric tractors like these tracklayers are said to have been a major success story in the 1940s and early 1950s.

British efforts

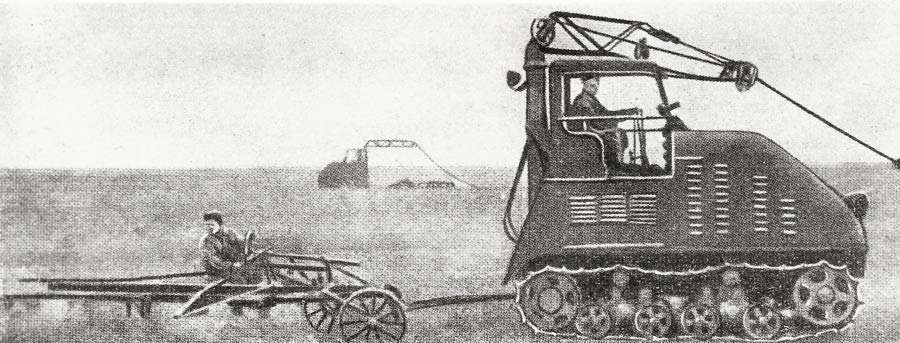

A British attempt to overcome some of these problems was shown in 1949 when the Electrical Research Association, based near Reading, Berkshire, demonstrated a Ransomes MG tracklayer that had been modified by fitting a 9hp electric motor instead of the usual petrol engine.

The electricity supply came through a cable connecting the tractor to a power point at the top of a 35ft-high pylon in the middle of the field.

The connector could turn through 360deg, allowing the tractor to work in ever-decreasing circles, and as it progressed closer to the pylon, counterweights took up the slack to keep the cable under tension.

The cable used for the demonstration allowed the tractor to work in a circle with 110ft maximum radius, which could presumably be increased by using a longer cable, but the rotary work pattern might be a problem on farms that do not have circular fields.

This Ransomes MG tracklayer with an electric power conversion was designed to work in circles around a central power point.

Cable-free tractors

A self-contained tractor that generated or carried its own electricity supply would avoid the need for a supply cable, and this was the approach used by American research teams.

Agricultural engineers at South Dakota State University started work on their Choremaster tractor project in 1983, using two 32-cell battery blocks to produce a 43.5kWh electricity supply powering two motors.

One motor operated the hydraulic systems, including the power steering plus the pto, and the other powered a three-range hydrostatic transmission with four-wheel drive.

Because of the limitations of battery power in the 1980s, the Choremaster was designed mainly as a yard tractor working within easy reach of a power point for battery charging.

The two batteries weighed about 2t and it took eight hours to recharge them fully to provide about six hours of work time.

The Choremaster was used for several years on the university farm, and the engineers also developed a battery-powered skid-steer loader.

Fuel cells

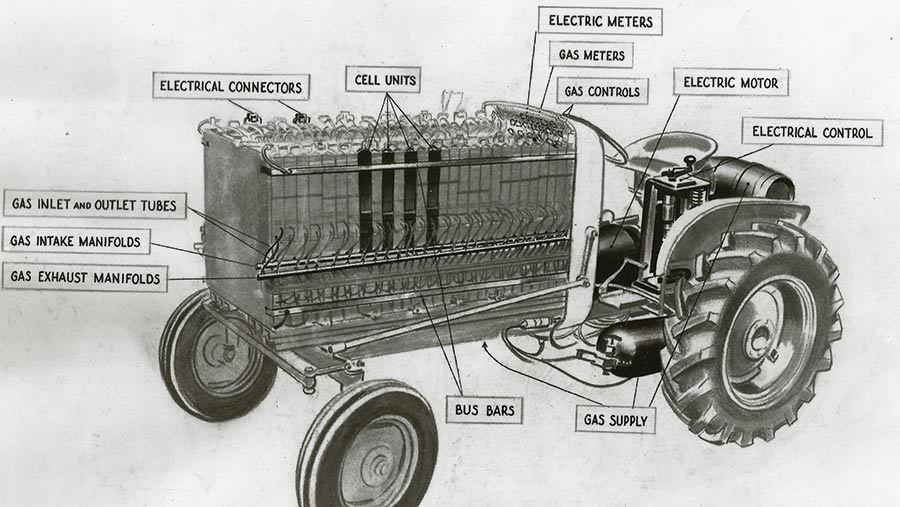

The first vehicle powered by electricity from a fuel cell was an experimental tractor developed by the Allis-Chalmers company during the 1950s.

Fuel cells were first developed by a British scientist in the 1830s, but they were not used commercially for more than 100 years.

A fuel cell works like a battery, using a chemical reaction to produce electricity, but, unlike a torch battery, the cell does not contain its own chemicals or “fuel” and does not have storage capacity.

Allis-Chalmers demonstrated this experimental fuel cell tractor in 1959

Fuel cells produce electricity, while the chemical supply is maintained, but stop when the supply is switched off.

They can work with a wide range of fuels, including liquids and gases, and Allis-Chalmers chose a mix of gases, including methane and propane.

Research into this area was a logical development for Allis-Chalmers.

As well as making tractors and farm machinery, it was also a major manufacturer of electrical equipment, including electric motors, and success with the fuel cell tractor project could have benefited both sides of the company.

The programme began in 1958 with fuel cells and an electric motor replacing the 31hp engine in one of its production tractors.

It was followed in 1959 by a specially designed tractor with 1,008 fuel cells filling the space normally occupied by the engine and supplying electricity to a 20hp motor.

Allis-Chalmers continued its fuel cell tractor research for several years, but the market was not ready for this type of technology. The benefits included low vibration and noise levels long before driver comfort had become an important sales feature.

Fuel cells also offer environmental advantages such as cleaner exhaust emissions and using renewable fuels, but the connection between vehicle design and protecting the environment had not become a major issue.

A cutaway diagram of the Allis-Chalmers fuel cell tractor

Modern-day development

In commercial terms, the Allis-Chalmers fuel cell tractor project was a failure, but, more recently, electricity has been emerging as the preferred option for a more environmentally friendly alternative to petrol and diesel engines for powering vehicles.

Fuel cells feature among recent projects, with New Holland demonstrating its NH2 experimental tractor in 2009, powered by fuel cells producing electricity from a reaction between hydrogen and oxygen.

Power output was 106hp and pure water was the only by-product, with no pollutants.

A potential attraction of using electric tractors is that on many farms they could operate on a home-produced electricity supply using methods such as biodigestion or wind generation, offering financial savings to help offset the probable additional capital cost of an electric tractor.

Small-scale commercial production of tractors using rechargeable batteries has recently started from Fendt and the Escorts company in India, with other firms currently involved in a range of research projects.

These include John Deere’s futuristic GridCON experimental driverless tractor producing up to 400hp using electricity delivered through a cable link.

Ideas for the future on John Deere’s GridCON experimental electric tractor include driverless operation and up to 400hp available