Why heat detection collars save time in an autumn-block herd

© MAG/Shirley Macmillan

© MAG/Shirley Macmillan Tail paint, once the foundation of block-calving fertility, has been replaced by heat detection collars in one 260-cow herd in Somerset.

The old go-to for identifying cows on heat proved to be less effective when the herd, at Volis Farm, near Taunton, changed its calving pattern from spring to autumn.

See also: Are fertility monitors worthwhile in block calving herds?

Herd manager Jack Pettitt explains: “As a spring-calving herd, we always used tail paint: cows were out in the field and the paint rubbed off completely.

“When we tried it on the autumn herd [in 2022], we found the cows were riding less intensely, for a shorter duration, and although the paint would be dirty, it wasn’t rubbed off.

“This was because they were housed full-time on 1 November ready to start serving on 10 November, and concrete is hard and slippery compared with grass.”

The spring herd was established in 2002 as a system to cut costs and make life simpler. However, it became obvious to business owner Caroline Spencer that her grazing farm dried up in summer.

Buying feed to plug grazing gaps meant she was not achieving the goal of cheap milk production off grazed grass.

Switching to autumn sees cows dried off when grass growth declines, and they can go straight onto standing hay.

After four years of transition, this year will be the first with no spring calving cows.

Farm facts: Volis Farm, Taunton

- 260 cross-bred cows

- 100 youngstock

- Autumn block calving

- 100ha (247-acre) grazing platform

- 27ha (66 acres) silage land

- 27ha (66-acre) heifer support block

- Average yield 6,000 litres – target 6,500 litres a cow

- Milk sold for Somerset Brie

Low-cost autumn

The herd of 260 cross-breds will start calving on 10 August this year, finishing on 10 October. The target yield is 6,500 litres.

“This year we’ll do 6,000 litres from 1.2t of cake,” says Jack.

“It is still a low-input system with a focus on rotational grazing, but whereas before we produced 5,000 litres, now we’ve got the extra cost of silage making and housing, plus one extra labour unit in winter.”

Spring calving was designed as a one-man system. Now Jack works alongside assistant herdswoman Makenzie King, every day from 10 August to 1 February.

Then the workload drops to 1.5 labour units, releasing Jack for jobs such as fencing.

Having spent £400 a year on tail paint for 20 years, Caroline took some convincing to invest in collars, with starting prices from £98-£130 a collar plus hardware installation.

She also had to upgrade the farm’s wi-fi to get them to work.

Jack, however, is confident that payback will be within the collar battery’s six-year lifespan, through time saved observing cows, lower vet costs and improvements in fertility performance.

“We are no longer checking tail paint at every milking,” he says.

“We used to do four bulling checks a day for 20 minutes, with the last one at 8-9pm. On a dark, cold November evening, you wouldn’t want to do it.

“We have just one person in the parlour now who can concentrate on milking and can draft automatically.

“The time saved at peak service period is 45-60 minutes each milking [every day] in the first three weeks of mating. It’s a nicer experience.”

Collars v tags

As well as changing calving pattern, the farm stopped using a combination of four weeks of artificial insemination (AI) followed by sweeper bulls and shifted to 100% AI.

This was another reason for automating heat detection.

Replacement heifers are bred from cows calving in the first four weeks of the block; sexed semen is used on first-, second- or third-lactation animals, then beef semen is used for the rest of the herd.

Jack ruled out ear-tag systems as he thought they would be easily lost, yet a setup based on collars needed to “speak” to the automatic shedding gate, he says.

“Every morning, whoever is milking has to pull out bullers without needing to punch numbers in. The Allflex Sensehub did this for us.

“We now have a collar on every cow with a ‘rumination facility’, and there are 60 collars for bulling heifers, without rumination.”

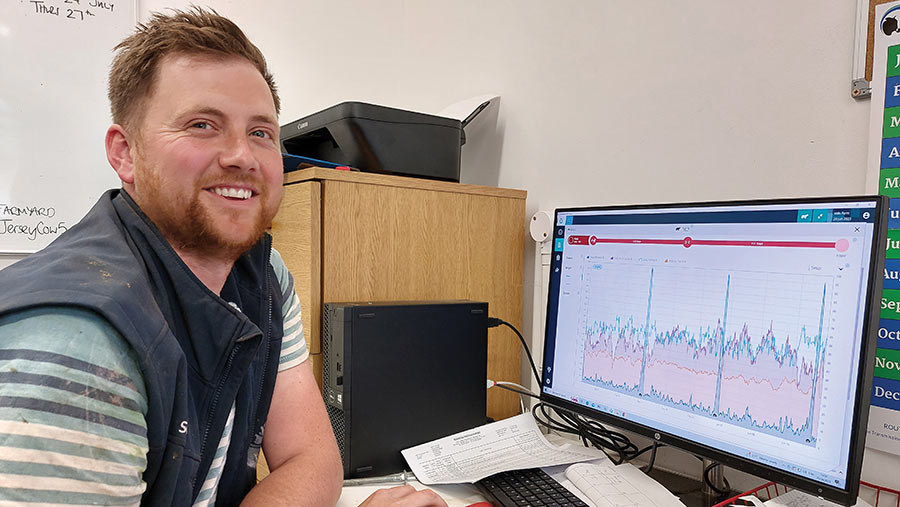

Jack Pettitt © MAG/Shirley Macmillan

Jack can now programme the software to select cows in heat and automatically draft them on exiting the parlour. He does this on the first day of serving and switches it off at the end of mating.

So far, he has found shedding accuracy to be around 98%. The software is on the office computer, as well as a phone app.

“I trusted this from day one. It’s important to get it up and running two months before you start serving and learn to read it, not a week before,” he says.

“It also worked well on our bulling heifers because it flagged up some that were not cycling.

“They were a bit immature, and we needed to weigh them to ensure they were on target, or [feed some] supplement. Now the collar picks up heats. It’s very useful and takes away guesswork.”

Bulling cows are served only once a day, in the mornings, for simplicity, and Jack will serve a cow if she is on the list.

He has found no difference in conception rate whether she was inseminated at the start, middle or end of standing heat.

Any cow not seen cycling one week before mating will get a vet check. With tail paint, they knew whether a cow was cycling, but the collars can say how regularly this occurs and identify irregular heats. “It can sort out cows for drying off too,” he adds.

Further benefits include using rumination and movement to flag up cows that may be sick, or suspected abortions. With winter rations based on block silage plus cake flat-rate fed in the parlour, the collars are not used to tap into any nutritional plans, although Jack says he is “still playing with all of the functions”.

© MAG/Shirley Macmillan

Pregnancy function

Next year, Jack plans to use the “pregnancy probability” data supplied by the collar.

“Thirty days after service it will flag up as ‘probably in-calf’ because she hasn’t come bulling at 21 days.

‘Low probability’ cows would be about 10% of the herd and will be checked by the vet to see if they are empty,” he says.

His view is that the £600 saved on a vet pregnancy diagnosis visit can be better spent on prevention, making sure that cows get back in-calf in the first place.

His aim is to get more cows back in-calf, sooner, by using the collar system. And results for the 2022 breeding season have now set a baseline for improvement.

“We had a 10% empty rate for the spring herd, and the only fertility key performance indicator we used to use was 50% calved in the first two weeks. Now we will have targets as we can measure.

“This is this the first year we have a six-week in-calf rate and we have had an overall conception rate of 53% for first lactation heifers, with 1.4 services/conception.”