Counting the cost of bovine TB in Wales

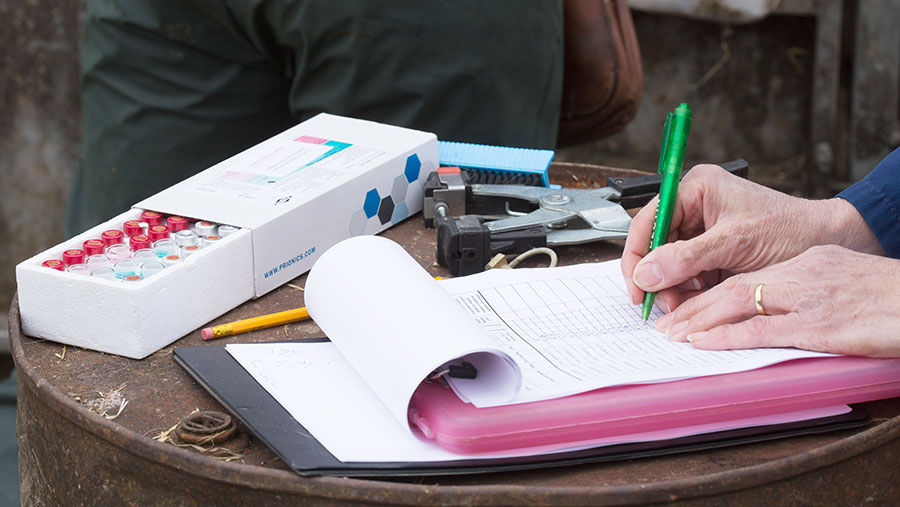

© Tim Scrivener

© Tim Scrivener Seen as a well-informed strategy by some, a misguided experiment by others; more than two years after the Welsh government rolled out its new policy for eradicating TB, it continues to divide opinion.

Recent figures show that its approach has resulted in a record 12,799 cattle being slaughtered in Wales in the 12 months to August 2019.

See also: Brian May’s Gatcombe Farm project secures TB-free status

A reason for this high number is that, since new enhanced control measures were introduced in October 2017 when the refreshed Bovine TB Eradication Programme was launched, Inconclusive Reactors (IRs) in herds with persistent breakdowns have been removed and culled.

Those running the programme suggest that 40% of those animals are likely to be harbouring the disease and would be an infection risk to healthy animals if they remained in herds.

Killing badgers – a potential solution?

In Wales, when a herd has been under TB restriction for 18 months a plan of action is put in place and the potential causes of continuing TB cases are considered.

Any actions required by the farmer and APHA Wales are agreed in areas such as herd biosecurity, environmental exposure – and wildlife.

An assessment is made of the likely risk of new infection from wildlife, and a priority score given based on wildlife activity on a farm and on TB findings in local badger carcasses submitted to the Badger Found Dead survey.

The government knows there is a reservoir of infection in badgers because the Badger Found Dead survey shows this to be the case.

But a promise to trap, test and cull infected badgers on farms with chronic breakdowns has only been delivered on very few of them.

In 2017, 37 badgers were trapped and five tested positive and were removed. In 2018, 120 were tested and 26 infected animals removed.

Trapping and testing is expensive, but so too is the cost of compensating farmers for their cattle.

In contrast, tens of thousands of badgers have been destroyed since culling was authorised as a TB control method in England.

In Wales the Labour-led administration has steadfastly ruled out an England-style cull, although rural affairs minister Lesley Griffiths recently told farmers she was reviewing the science behind culls and the subsequent reduction in TB levels.

If the government is averse to culling badgers, farmers are questioning why other available methods to detect the disease in badgers, such as testing badger faeces for TB infection, known as a PCR test, are not used.

The reason seems to be that they produce a high level of false positive results, where TB-free setts are incorrectly identified as infected with TB.

But the government is understood to be working with Prof Liz Wellington, who developed a PCR test at Warwick University, to improve that test with a view to applying that technology in Wales.

In published studies, IRs have been identified as a risk; in an unpublished analysis of long-term persistent herd breakdowns in Wales, IRs at severe or standard interpretation were found to be three to three-and-a-half times more likely than clear testing animals to become reactors at subsequent testing.

Persistence

Alan Huxtable, veterinary lead Wales at the Animal and Plant Health Agency (APHA) Wales, has suggested that leaving infected animals in a herd may lead to the disease persisting “for years”.

The TB skin test at standard interpretation remains a good herd surveillance test, he believes, but it may not be detecting 20% or more of the infected animals in herds.

But farmers whose herds have been decimated by this policy point out that, by the government’s own admission, 60% of the IRs culled would not have contracted TB in their lifetime.

So is the government removing more animals than it should?

If there is a risk of those animals being infected, government vets would reason that it is surely better to remove them at the earliest possible stage. Put that way, it is difficult for farmers to argue the contrary.

But it really comes down to the accuracy of the testing and an additional tool will be added to disease surveillance in Wales next year.

Additional tool

The World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) has validated Enferplex, an antibody test that picks up infected animals missed by cell mediated tests.

It is understood that it will be used in persistent breakdown situations in Wales next year.

Prof Glyn Hewinson, a world-renowned bovine TB expert who is leading a new Centre of Excellence for Bovine TB at Aberystwyth University, said the test is capable of identifying around 90% of all animals that have lesions.

“On their own, antibody tests are not very sensitive, but if used 10-30 days after the skin test, there is a good antibody response,” he explained.

“If you are trying to remove infection from known infected herds, a combination of two tests is better than one for detecting infected animals.

“In persistently infected herds there will be some infected animals missed by the skin test and gamma testing. Antibody testing can be used to identify those animals.

“An IR is a high-risk animal and three tests might help give a better picture of the disease status of that animal than two.”

But Enferplex can’t be used to negate a positive skin test, Prof Hewinson cautioned; if an animal has a positive skin test, but is antibody negative, it cannot be left in the herd.

Case study: Keith Pugh, Gwndwn, Llandysul, Ceredigion

Keith and Bethan Pugh

A powerful example of how the enhanced control measures policy can wreck a business can be found at Gwndwn, a dairy farm run by Keith Pugh.

The farm, near Llandysul, Ceredigion, has experienced sporadic herd breakdowns since 2004; it would lose three or four cattle at each test failure before the herd tested clear again.

That changed this year, once the herd had been under TB restrictions for 18 months and enhanced control measures were applied.

Since May 2019, Mr Pugh has lost 51 cattle in two tests, 60 days apart. The herd will be tested again this month.

“It has been devastating, it is absolutely crippling us,” admits Mr Pugh, who farms with his father, Graham. “I make no apologies for admitting that I cried when the vet was tagging those animals.”

Under a standard test, Mr Pugh says he would only have lost one of the 21 animals culled in May.

“The government suggests that 40% of the others would in future have been reactors, so by its own admission 60% wouldn’t have, so 12 of the cows I lost in that test would not have gone on to contract TB,” says Mr Pugh.

“Our herd isn’t pedigree, but my father began breeding over 50 years ago and it upsets me greatly that I cannot protect the herd from this flawed Welsh government policy.”

Cattle controls

Mr Pugh doesn’t want TB in his herd. “No farmer does,” he says. But he disputes the government’s approach to eradication, which is heavily weighted towards cattle controls.

He has a very large population of badgers on his farm but, despite a pledge by the government to roll out wildlife controls on farms with chronic herd breakdowns, that has not happened at Gwndwn.

“We are convinced that TB infection in wildlife is having an impact on our herd, but we are not considered a priority,” says Mr Pugh.

He insists he has done all he possibly can to remove bovine TB from the farm – running a closed herd by using sexed semen to breed replacements and having double fencing between him and neighbouring farms.

“We have showed people from the Welsh government all our badger setts, there is plenty of evidence of badger activity, and we have been promised that we will be pushed up the priority list. But as far as I am aware they have only trapped and tested badgers on a handful of farms.”

Mr Pugh’s all-year-round calving Friesian herd is run in a housed robotic milking system.

Two milking robots were installed in 2012, when Mr Pugh was milking 120 cows. He now has 78 milkers.

“We are milking 65 at the moment, we could potentially shut down one of the robots because it is costing us money to keep it running, but I would be concerned about the problems we might get when we needed to start it up again,” he says.

“I don’t call the money we get for the cows we lose ‘compensation’; the government is compulsorily purchasing animals that it considers a TB risk, but this is destroying our business.

“It removes our ability to produce milk from those animals and there is no financial acknowledgement of that.”