Video: Brian May’s Gatcombe Farm project secures TB-free status

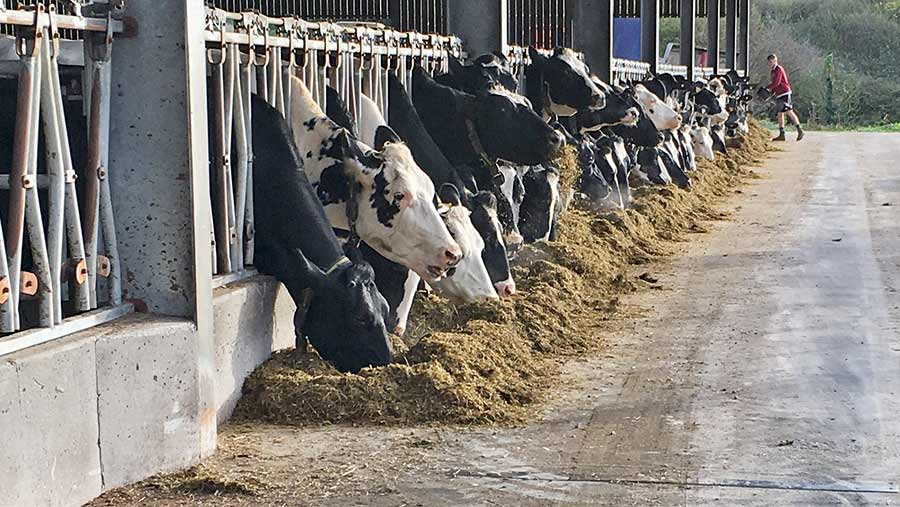

A new approach to disease control on a dairy farm in Devon – taking out infective cows and minimising exposure to slurry – has seen the herd attain TB-free status after six years of persistent breakdowns.

The farm in question is Gatcombe Farm, run by Robert and Thomas Reed.

They have been involved in a five-year project overseen by Dick Sibley of West Ridge Veterinary Practice, Tiverton, in partnership with Queen guitarist and animal rights supporter Brian May.

See also: What a new bovine TB test trial in Devon means for farmers

Mr Sibley was already working on the holding when he found undisclosed, infected cows which the skin test had failed to identify. Subsequent tests of their faeces had also found Mycobacterium bovis, suggesting this might be a significant transmission route.

This chimed with observations made by Dr May and his team from the Save Me Trust following visits they had made to other farms in TB hotspot areas.

“We noticed a gathering number of clues,” Dr May told Farmers Weekly.

“We noticed on one farm that the cows were paddling around in a lot of their own excrement. We asked, naively, how come this is not important, when you are worrying about a tiny amount of excrement from a badger? They said, ‘Well, it’s just not important. It’s the badgers that are doing it’.”

“We also witnessed the skin test and saw how hit-and-miss it was, and we noticed the amount of stress that was involved.

”The farmer is obviously massively stressed, because his whole livelihood is threatened.

“This stress transmits to the animals, which were defecating the whole way through and looking panicked. So, by the end of the skin test they were literally paddling around ankle deep in cow poo. This gave us a bad feeling and made us ask questions.”

Transmission pathways

These concerns were shared with Mr Sibley, who was already starting his own investigation at Gatcombe Farm.

“We looked at every conceivable transmission pathway,” Mr Sibley explained. This included testing the badger population, with some 273 faecal samples collected and analysed, a third of which were found to be contaminated with M bovis.

“But one thing we noticed was that the only cows going down with TB were the milkers that were housed 365 days a year and never had any contact with badgers,” he told Farmers Weekly. “The livestock that had access to the pastures never appeared as reactors.”

So attention shifted to the cows and the slurry pit.

“As part of our investigations, we found some cows which were shedding large quantities of organisms in their faeces, despite testing negative in the statutory testing programme,” Mr Sibley said.

The conclusion was that there were three types of animals in the herd of over 300 cows:

- Non-infected, but susceptible to TB

- Infected and latent (not actually shedding the disease)

- Infected and shedding TB bacteria

But were badgers still partly to blame? Dr May is adamant they were not, maintaining it is far easier for badgers to contract the disease from cattle than the other way around.

“It’s quite easy to figure it out, because the cow excretes a lot of stuff,” he said. “In the open, there are cow pats everywhere, they attract slugs and worms – nice food for the badgers. It’s very easy for the badgers to pick up the infection.

“But the transmission from badger to cow is not so easy. Number one, cows and badgers are not normally in close proximity, so sniffing is not the main vector. So the cow would have to ingest excrement from badgers.

“Now, badgers will roam around the pastures at night, but they do not defecate there. They only wee and poo in their designated latrines – away from where the cows are grazing. They are very fastidious.”

Given this “presumption of innocence”, the focus at Gatcombe has been on selective culling and rigorous hygiene, as well as vaccinating the badger population to try to reduce any potential environmental contamination (see panel).

The Gatcombe method

The Gatcombe Farm project is a two-part process – removing cows that are thought to be shedding TB and cutting off all routes to possible infection through faeces.

- Culling out. The first part of the programme was to test the cows and identify those that could be classed as “shedders”. This involved using the new Actiphage test, developed by Nottingham University, which detects the presence of the TB bacterium in cows. A second test – a quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) test developed by Warwick University – was used to find the bacteria in the dung. Animals found to be positive to both were culled or isolated.

- Routes to infection. A whole series of measures have been taken to minimise the risk of cows ingesting faeces which might be contaminated with TB bacteria, including:

- Automatic scraping of all passageways in the buildings

- Installing a rubber matted calving area, which is disinfected regularly

- Use of a dedicated tractor for distributing feed

- Raised water troughs, reducing the chance of faeces contamination

- All slurry from the lagoon taken off farm and incorporated into arable land only

- All bought-in cattle sourced from low-risk herds.

The results

The programme introduced by Mr Sibley and his team appears to have been successful, as the herd of more than 300 cows was declared TB-free in March this year.

Mr Sibley attributes this to the elimination of contaminated faeces in the cows’ environment.

“The biggest improvement to human health over the centuries came from the development of sewers,” he said. “Maybe we should start doing that for cows. Living in your own muck is not good for you.”

But Mr Sibley is also aware that the disease could return. “We know there are probably shedders still in the herd which we have not found yet.”

According to Dr May, there is an anomaly because, now that the herd is TB free, the vets are not allowed to carry out enhanced testing.

“It is a bit of a nonsense and I think it should be changed,” he said.

“For the time being, we know that Gatcombe has TB-free status. But we also know that, at any time, we will get a reactor.

“As soon as a reactor is found, we can go back to the enhanced testing and completely eliminate TB in the herd.”

Q&A with Brian May

PC: Whatever the success of the project, it’s just one trial on one farm so does not really prove anything.

BM: I agree, it’s only a small experiment. We plan to roll it out further. We desperately need a proper trial, but we don’t yet have the support of Defra. There is an opportunity in the Gower peninsula in South Wales, however, if we get funding. We think that these results will be reproduced there and then it will be very hard to doubt that the reservoir of infection is not in wildlife, it’s in the herd.

Brian May, left, with FWi executive editor Philip Clarke

Have you presented this to other vets and farmers, and what reaction do you get?

We’ve had some farmer meetings and generally the response is very good. The farmers come in very suspicious and wondering why I am there. But Dick, by telling his story simply, convinces pretty much everybody he talks to. We would like to go out and do this more: talk face to face, present the story and give farmers the opportunity to evaluate it for themselves.

Clearly you are opposed to badger culling. But the Godfray review last autumn said “the presence of infected badgers does pose a threat to local badger herds”, while the recent Downs report points to a clear 66% drop in TB incidence in the cull area of Gloucestershire, 37% in Somerset.

In the places where they are doing the culling, they are also implementing other farming controls, so you will never know what caused a betterment, if you get one. Plus, the claims that have been made just recently – a 66% decrease in bovine TB in Gloucestershire – failed to include the latest data.

If they had included the 2018 figures, they would have to admit that all the gains have been undone. There is no evidence that the badger cull is working. Even Godfray says it’s a mistake to put too much importance on the influence of badgers.

Over the long-term, 60 years, it is clear that TB only took off again after badgers became a protected species in the 1970s and culling stopped. Mere coincidence?

At exactly the same time as badgers became a protected species, farmers stopped composting their slurry and started putting it in slurry pits.

Composting, as we all know, heats up the residue, basically pasteurising the excrement so it no longer has live organisms in it. When that stopped, the whole business of slurry resting on the farm untreated in slurry pits came about. Isn’t it possible that’s the reason for the TB increase?

You are often seen as being anti-farmer. How do you respond?

We’ve never been confrontational towards farmers. If that were true, why would we have been working for the last five years with a dairy farmer at Gatcombe, helping him convert his farm from a chronically infected, permanently shut-down situation to TB-free status? Please put to bed the myth that Brian May is anti-farmer.