Genetic testing nets US dairy farmer extra income

Evaluating the genetic potential of herd replacements is allowing one US-based dairy farming business to earn an average of $500 (£402) above market prices on annual sales of up to 200 heifers.

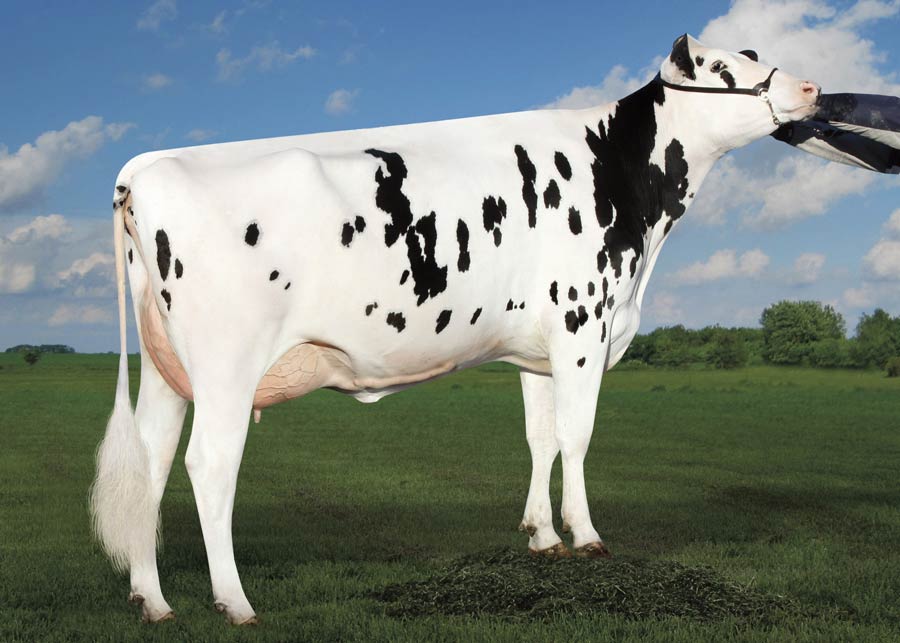

Milk producer Robert Webb generates additional income from selling progeny from his 750-cow pedigree Holstein herd from his farm in Wisconsin, in America’s Midwest.

See also: Wagyu DNA tag

Mr Webb has used genetic testing to shape the herd for the past eight years.

“We are paid an average of $2,500 [£2,009] for replacements. We think genomics has contributed an average of $500 [£402] to that price, mainly because of high-quality type that genomics gets right – the type information is accurate.”

© Nick Sarbacker

Ear-notch samples are taken from young calves to give a DNA profile of the economically important traits he identified as important to his herd.

These characteristics are also valued by farmers who buy progeny from his herd and include protein, type and health traits.

“The data allows us to sort the herd and prioritise the animals we want to breed from. It gives us nice cows to work with,” explains Mr Webb, who farms with his wife, Peggy, and sons, Jim and Joe.

The business uses Zoetis’ Clarifide test to predict genetic merit from core traits.

“The test allows us to run a larger profile if needed,” says Mr Webb.

The Webbs, who trade as Summit Farms, sell between 15-20 heifers a month. The availability of genomic data allows them to command premium prices for these animals.

See also: UK dairy farm benefits from using genomics

“My buyers want quality cattle, and type is important to them,” says Mr Webb, who says genomics takes the guesswork out of breeding and management decisions.

Summit Farms covers 445 ha (1,100 acres) and has a housed dairy system. Cows are milked three times a day, averaging 45 litres/day (100lbs/day).

The herd has a rolling 23-24% pregnancy rate per service.

Developing and selling offspring is an important part of the business.

The family’s interest in genetics started 20 years ago when they created a sire breeding business.

The value of genomics – the facts

- Every bovine has a unique genome and it is these differences that will identify highly productive dairy cows.

- The selection of breeding animals once relied on testing bulls by observing how their daughters performed but this involved large numbers of cows and took many years to complete.

- A major advantage of genomic selection is it dramatically reduces the timescale of this selection process. Genetic composition of bulls and females can be completed at an early age.

They were part of the Multiple Ovulation Embryo Transfer programme designed to develop the next generation of bulls in stud.

“Cows were farmed out to operations like ours, and we shared the offspring, resulting in some new cow families on our farm, including Webb-Vue Goldwyn Elvira,” Mr Webb explains.

He teamed up with Select Sires to test for early genomics.

“That’s really how Elvira was discovered,” says Mr Webb.

“We are now watching grandsons and great grandsons of Elvira attracting attention.”

Select Sires now mates his cows using the World Wide Mating Service program.

For many years, the Webbs have been sampling Select Sires’ young sires as part of the Program for Genetic Advancement.

They also have a herd agreement with Select Sires, allowing the stud first right of refusal for all artificial insemination-potential bulls on the farm.

“Select Sires sends us pre-release semen to use for flushing and to breed our high-genomic animals and the company has the rights to all of our bulls until they release them,” says Mr Webb.

Top heifers are selected based on Pedigree Total Performance Index (PTPI) and embryos are flushed from the best females.

“The majority of flushing is done on virgin heifers with the highest PTPI values, with emphasis on protein, type and health traits,” says Mr Webb.

He uses high ranking genomic young bulls, aiming for 20-30 females from a single sire.

“The calving ease data is also of high value,” he says.

He is confident genomics creates extra value in a dairy herd.

“Thanks to genomic testing and embryo transfer we are seeing a 10% increase in production across the herd.

“Genomics gives a broader identification for each cow and aids genetic improvement. In our business it brings tremendous value to marketing extra females and males.”

How UK farmers can use genomics and identify better breeding stock

Genomic testing heifers enables dairy farmers to make data-driven breeding decisions based on accurate facts.

At the very minimum, it identifies which animal’s farmers should rule out from breeding their next generation of milking cows, insists Mike Halliwell, of World Wide Sires UK.

“I tell farmers that genomics is the best technique they have available for interviewing the next employee, in this case their heifer replacements.

“Screening the next generation of animals that are potentially entering the herd means they can identify which are worth investing in for the future.”

It identifies the animals a farmer should not want to invest in. A herd will always have the “high flyers, the average performers and those that are below par,” says Mr Halliwell.

“If you take out those at the bottom, you raise the herd average and the business can move forward at a more sustainable rate.”

In his experience, there are three main reasons why animals exit the herd – infertility, high somatic cell count/mastitis and conformation linked mostly to lameness.

Animals genetically hard-coded to be transmitters of these undesirable traits should not be used to breed herd replacements.

“Put them to a beef bull,” advises Mr Halliwell.

“By all means use those animals to produce milk but don’t allow them to contribute to the herd’s genetic pool.”

Heifers calves that don’t make the grade should be sold. “The traits identified might be below the herd average but could suit the purpose of another milk producer, in that sense it is not a case of offloading poor-performing animals.”

Although Mr Halliwell believes the industry is a long way from a situation where dairy farmers request genomic profiles when buying replacements, it is at the point where genomics can help dairy businesses add value to animals that are above average, as in the case of Summit Farms.

“Data is everything,” says Mr Halliwell.

“There is no emotional attachment to data.

“There may be farmers who think they can roll along in a very relaxed way but they then shouldn’t be surprised if they find they are not making any real improvement.”

He recommends dairy farmers use genomic profiling to quickly exit animals from the bottom of their reference population but understands a reluctance in situations when every animal counts, particularly where bovine TB is a complicating factor.

“Some farms will want to keep every animal as an insurance against losses but if they take out a percentage and sell those animals for the similar value of a Continental calf, they are freeing up cash to reinvest in the herd.”