Gold Cup winners 2003: Where are they now?

Saunders family

Saunders family The Sanders family have completely overhauled their business since winning the NMR/RABDF Gold Cup.

The family, famed for turning out 120 cows with a 100t lifetime production – the most in Europe – has switched to a lower-input, grass-based system.

Seventeen years since winning the coveted trophy, Andrew Sanders, who runs the Sandisfarne herd on the Isle of Man with his wife, Sue, and sons, Matthew and Julian, has swapped pedigree Holsteins for cross-breeds, upped numbers from 280 to 600 cows and turned to block calving.

See also: How to decide if autumn block calving is right for your farm

After Sue was injured during milking, the family decided to move from milking three times a day, yielding 12,000 litres, to twice-a-day milking, producing just over 8,000 litres.

Farmers Weekly asked Mr Sanders about some of the main changes.

Farm facts

- 320 Holstein and 300 Swedish Reds. Holsteins now put in calf to Friesian and breeding from Holstein Friesian-crosses

- Calves outdoors from late March to mid-July

- Farms 304ha (750 acres), with 154ha (380 acres) owned

- 1,500mm rain/year

- Yields 8,100 litres at 4.35% butterfat 3.52% protein

- In 2003 the farm averaged 12,000 litres of milk a cow, at 4.1% butterfat and 3.2% protein

What is the biggest change you have made?

We have moved away from chasing yield and instead focus on profit margins and lifestyle. We have gone from running a high-yielding, top-pedigree Holstein herd requiring a lot of bought-in feed to a lower-input, grass-based system, using a mix of Holstein, Swedish Reds and cross-bred cows.

When we won the Gold Cup, we were milking three times a day and at our peak, we were averaging 12,000 litres a cow.

The Holsteins were so high-yielding, we were pushing for longer lactations, with cows calving every 18 months, and a voluntary waiting period of 100 days.

We did not need to get them in calf every year when we had some cows that were maintaining 16,000 litres.

However, in 2008, Sue got injured while doing the night-time milking, so we stopped milking three times a day and decided to rethink things. We opted for a low-input system.

The simplification of the system and drive to minimise costs at every opportunity has resulted in an overhead cost of just 10.5p/litre, which is significantly lower than other herds costed by our consultant, P&L AgriConsulting, which averages 18.9p/litre.

Why did you change your breeding policy?

The Holstein was getting too big and genomics was favouring an indoor cow rather than one that could make the most from grazed grass. To keep the condition on them, we had to feed more concentrates and the economics were not stacking up.

We decided to focus on breeding a smaller cow that could get more from grass while maintaining fertility.

We initially went down the route of producing the Procross by cross-breeding Swedish Red and Montbeliarde, while maintaining half of the herd as pure Holsteins.

However, we didn’t find enough of a difference to make it worthwhile. We liked the Swedish Reds, so we crossed them back to Holstein to maintain some stature as pure Swedish Reds only weigh 500kgs compared to 750kgs for a Holstein.

However, in the past two years we have been putting British Friesian onto the Holstein to produce a smaller black-and-white cow.

We sell a lot of breeding stock and most of our buyers prefer a black-and-white animal. The first cross-bred Holstein cross Friesian heifers will be calving in the spring next year.

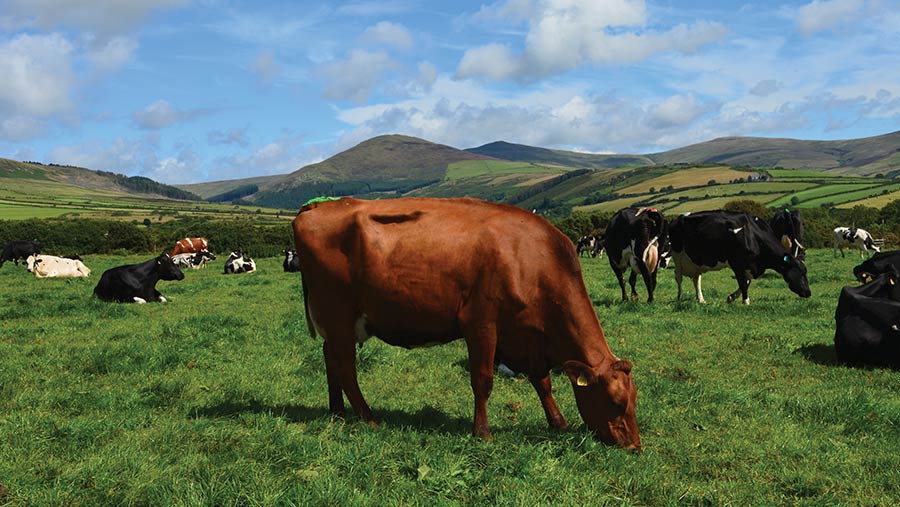

Cows are grazed during the spring and summer © Andrew Sanders

Have you reduced concentrate input?

When we were feeding a 12,000-litre cow, we gave each cow about 4t of cake. That is now down to 1.75t. We gave up feeding a total mixed ration (TMR) 12 years ago to make more from grazed grass.

Forage costs sit at 2.2p/litre, which is the same as the average costed by P&L AgriConsulting.

Cows rotationally graze 42 paddocks for at least seven months of the year and are housed at night in October.

In the winter, they are fed round bale silage and concentrates in the parlour. We produce 6,000 bales of wrapped silage a year – something we have done since we took on the farm in 1996, as there was no silage pit when we arrived.

We have never looked back. The round bales are easier to cart to the 600 heifers being reared away from the farm.

What have been some of your main investments?

After Sue was injured, we decided to install a 40-point Milfos rotary parlour to make things easier. It cost us more than £200,000. We have a robotic arm in the parlour that pre-sprays the teats.

We also invested in youngstock and cubicle sheds.

Some of our main machinery costs have come from silage-making equipment, but our power and machinery cost a litre is exceptionally low at 2.98p/litre, as we are no longer feeding a TMR.

This is significantly lower than herds benchmarked by P&L AgriConsulting, which have an average power and machinery cost of 4.88p/litre.

We have a full range of grassland equipment, except for a baler, for which we use a contractor. We do all our own umbilical slurry spreading, spraying, fertiliser application and reseeding.

We invested in a Bauer slurry separator and green bedding and this has saved us a fortune on bedding costs, especially on the Isle of Man.

Bits of kit such as umbilical slurry-spreading equipment, automatic scrapers and separators have made a huge difference.

Slurry is being used better, there is less damage to the fields and we can pump it out quicker. We also burn less diesel while carting slurry around and use less fertiliser because slurry use is more efficient.

How has the dairy market changed since your win?

Milk quotas have disappeared. However, the Isle of Man never had quotas, which is one of the reasons we first moved here.

We supply the Isle of Man Creamery on an A+B pricing system. Our A-quota is based on monthly supplies from October to January.

Extra milk sold in April, May and June is paid for at the B-price, which is why we calve in the summer, so our cows are at peak yield when we are getting paid the most for our milk. Our milk contract requires cows to be grazing for at least 200 days a year.

The creamery still mostly supplies doorstep deliveries (about one-third), but it has had to work hard to compete in a global market and sell our cheese to countries such as the US and Australia.

Where do you see the industry in 17 years?

I think there will be big incentives to invest in environmental measures. The Isle of Man is classed as a Unesco biosphere – so it will be at the forefront of green energy.

The future is going to be focused on trying to get the highest price for the best milk.

The next generation is also showing an interest in the farm. My sons are taking over now and doing most of the decision-making. My eldest granddaughter, Holly, is fanatical about the cows, and some of the other grandchildren are interested too.