Sussex wheat grower sees high yield even after nitrogen cut

Robin Kelly, Stephen Woodley and David Ellin in a field of the winter wheat variety Basset © MAG/David Jones

With cereal growers coming under increasing scrutiny to use nitrogen fertiliser wisely for environmental and economic reasons, we take a look at how they can cut rates and still maintain yields.

In the first of a two-part series, we visit a South Downs grower in West Sussex who is cutting his nitrogen rates without harming yields and limiting any leaching.

In the second part, we will look at how encouraging rhizobacteria levels in soils can also reduce nitrogen rates and even lead to yield increases.

Lower nitrogen, high yields

David Ellin is cutting back on nitrogen fertiliser without reducing the yield of his winter wheat to help reduce the chance of nitrates leaching in his light chalky soils.

High up on the South Downs, overlooking Shoreham, he is using a liquid urea polymer to save him just over 30kg/ha of nitrogen, which might have ended up in Brighton and Hove’s water supply.

See also: Berks wheat growers cuts nitrogen and hits milling protein

Farm facts

- Lower Paythorne and Perching Manor Farms – 625ha, owned by BD Harris Trust, near Fulking, West Sussex

- 400ha – Downland (120ha of arable with the rest grassland)

- 225ha – Heavy weald clay, largely arable

The West Sussex farm manager is applying this polymer product in May to cut his overall nitrogen use down to 169kg/ha, but still keeping his biscuit-making wheat yields more than 10t/ha.

“The yield is similar and the costs are similar, but we are saving more than 30kg/ha of nitrogen, which could have been leached away,” he tells Farmers Weekly.

Carbon footprint

This approach could be very useful as farming looks to cut its carbon footprint and adapt to the new Environmental Land Management (ELM) schemes, both likely to mean lower or more efficient nitrogen use.

These new ELM schemes, to replace direct farm subsidies, are likely to include methods to aid sustainable farming and limit nitrogen leaching, such as using wide field margins, applying nitrogen more efficiently and growing cover crops.

On his farm, Mr Ellin is working with a number of partners, including Southern Water, to cut nitrogen and so safeguard drinking water that is drawn from numerous boreholes in the chalky Downs, and the early signs are promising.

The biggest leaching threat comes after harvest, so by cutting nitrogen rates and drilling cover crops after wheat, he is cutting down on the chance of losing nitrates to the water supply.

“We are avoiding high levels of residual nitrogen in the autumn, which is the most likely time for nitrogen leaching in our soils,” he adds.

His approach is to halve the farm’s standard 86kg/ha of ammonium nitrogen rate applied at the flag-leaf stage in mid-May, and then go a week later with the foliar product Efficient 28, which provides 7kg/ha, in effect replacing 43kg/ha of ammonium nitrate (see table, below).

Two nitrogen fertiliser regimes in trial |

|

|

Traditional nitrogen approach |

|

|

Early March |

Nitrogen and sulphur – giving 30kg/ha of N |

|

Mid-April |

Ammonium nitrate – 86kg/ha of N |

|

Mid-May |

Ammonium nitrate – 86kg/ha of N |

|

Total nitrogen applied |

202kg/ha |

|

New nitrogen approach with Efficient 28 |

|

|

Early March |

Nitrogen and sulphur – giving 30kg/ha of N |

|

Mid-April |

Ammonium nitrate – 86kg/ha of N |

|

Mid-May |

Ammonium nitrate – 43kg/ha of N |

|

Late May |

20 litres of Efficient 28 – giving 7kg/ha of N |

|

Total nitrogen applied |

169kg/ha |

Ideal application

His independent agronomist, Stephen Woodley, says the ideal application of the foliar product seems to be at the T2 flag-leaf stage, along with a fungicide on the biscuit wheat variety Basset when there is good leaf cover.

“The product is taken up well by the leaf. We have tried doubling the rate but it appears the leaf can only take up a limited amount,” says Mr Woodley.

Although there is no financial benefit replacing 46kg/ha of ammonium nitrate with 7kg/ha of foliar nitrogen, the liquid approach cuts down on the fear of leaching, and sees a near-100% uptake by the wheat plants.

“We are not seeing high residual nitrogen levels in the autumn, and the levels we are seeing of 35-60kg/ha can be easily be mopped up by cover crops,” he adds.

The farm has been using the polymer nitrogen product, made by Agro-vital, for four years – first on oilseed rape and increasingly on wheat.

It fits in well with the farm’s environmental aims of reducing inputs and disturbing the ground less to improve the health and organic matter of its light soils.

Direct benefit

There could also be a direct benefit to farmers – according to Robin Kelly, Southern Water’s risk management officer, payments for fewer and more efficient nitrogen applications could be an option in the future.

“There could be a financial benefit going forward if we can reduce the overall nitrogen level in the groundwater,” he says.

Mr Kelly adds that groundwater has seen rising nitrate levels, which are expensive to reduce, and that is why Southern Water helped set up The Aquifer Partnership (TAP), which launched in 2020.

This initiative brings together the South Down National Park Authority, Brighton and Hove City Council, the Environmental Agency and Southern Water to protect groundwater underneath the South Downs around Brighton, providing drinking water for 1.2 million people.

Mr Ellin is now working with the partnership on the 625ha Lower Paythorne and Perching Manor Farms he manages, which includes 400ha of downland and the rest heavy Weald clay.

When he arrived at the farm 10 years ago, it was decided to restart arable cropping on the Downs, which had become like a vast expanse of “green concrete” with limited food sources for birds, such as corn buntings and skylarks, as well as mammals and insects.

Food for wildlife

The growing of arable crops provides a valuable source of food for wildlife, with flower margins supplying pollen and nectar for insects, beetle banks a habit for insect predators, and fallow plots an excellent site for ground-nesting birds.

As well as the these environmental areas, cropping includes winter wheat, oilseed rape, spring barley and spring beans as well as cover crops, while the steep grass banks are grazed by a 100-strong suckler cow herd.

The move to arable cropping prompted a careful monitoring of nitrate levels, and this is the second year of checking levels coming from wheat.

The programme starts early in the year, with Mr Woodley taking core soil samples down to 600mm to test soil mineral nitrogen, which is usually low due to the thin soils and the heavy rain hitting the Downs.

A programme is devised for nitrogen fertiliser on the wheat crop, and at harvest, grain samples are analysed to calculate how much nitrogen is left over – which can depend on the mineralisation of nitrogen in the soil over the summer, as well as nitrogen applications.

Porous pots are then placed in fields reaching down to 750mm, and groundwater monitored from October to February to check on any possible nitrate leaching.

Low residual nitrogen

Early results indicate low levels of residual nitrogen after harvest that could be prone to leaching, but trials will continue to ascertain the full benefits of cutting nitrogen rates by using the foliar product.

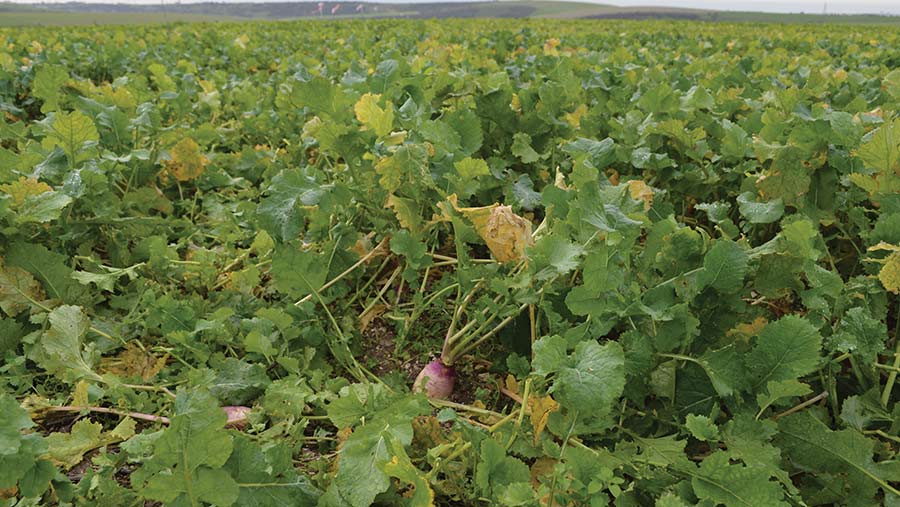

The winter wheat is followed by oilseed rape or a cover crop of a stubble turnips and forage rape mix ahead of a spring crop, and so no bare soil is left over winter to further minimise the leaching threat.

© MAG/David Jones

The polymer nitrogen is also working well on oilseed rape, on which it has been used for four years, by applying late foliar nitrogen along with a flowering fungicide spray.

This comes at a time when the farm is looking to improve its chalky soils by chopping straw, applying manures and moving to direct drilling or very minimal cultivations and away from ploughing.

Mr Ellin has been direct drilling his wheat with a Horsch Sprinter tined drill for the past three to four seasons, and this low-disturbance approach has seen soil organic matter levels rise to an impressive 5-6%.