Video: How a US potato grower is slashing pesticide use

© Rocky Farms

© Rocky Farms Growing potatoes on a commercial scale with virtually zero synthetic inputs would seem impossible, but this is exactly what one US farmers has achieved using what he calls “biotic farming”, without any detriment to yield and quality.

In part one of this two-part series, Brendon Rockey explains why he switched to his biotic approach across the 200ha Rockey Farms, Center, in south Colorado.

See also: Why one firm is using a biofungicide in its disease strategy

Farm facts: Rockey Farms, Center, Colorado

- 200ha of cropping

- 2,330m above sea level

- Rotation with two crops, potatoes and cover crops

- Potatoes grown with companion crop

- Use irrigation

Potato growers worldwide, Mr Rockey says, face many of the same challenges from insect pests, foliar diseases, soil-borne pathogens and weeds, and requirements for water and nutrients to grow potatoes.

“How we approach those challenges differs. Where we run into problems is where we have a linear thought process. We recognise the problem but only think about the direct impact on the crop and not its relationship to everything else around it.”

That pushes growers to use solutions out of a can, he says. The trouble is thinking like this doesn’t take other variables, such as beneficial insects, carbon, life in the soil and on the plant, into consideration.

Watch Brendon’s video on how he grows Fingerling potatoes and read the rest of the report below.

Harming beneficials

As a seed potato producer, he needs to control aphids transmitting virus. Mr Rockey’s early approach was to use insecticides, but they also have an impact on beneficial insects.

He says this approach is particularly problematic when growing monocultures. “If you’re growing a field of potatoes the insect pests have a food source, but the beneficial ones don’t, so once you take this approach you have no other choice but continue with it.

“It drives resistance, which means you have to use more product or change the products around, just to stay ahead of the new problem you have created.”

Insecticides can also negatively impact insects living on the surface or in soils. This can create other problems even though the aphid was the original one you were targeting.

The same applies to foliar diseases or soil-borne pathogens treated with fungicides. He points out that the number of beneficial fungi or bacteria far outweighs the number of pathogens, yet the pathogens get all the focus.

“We are willing to damage the beneficial components of the soil in order to attack the problem disease we have identified.”

But just as with insecticides, this continual attack on the beneficial fungi in the soil means that instant defence mechanism is no longer working effectively and the same cycle of resistance and increased use of fungicides is required, he claims.

He also believes the use of fungicides and soil fumigants contributed to problems arising with parasitic nematodes. “We didn’t have a problem with parasitic nematodes when we started growing potatoes, but saw the biggest problems where we used the highest amounts.

“It turns out beneficial fungi and bacteria help manage nematodes, or used to. Parasitic nematodes are a problem we created by taking the wrong approach to solving a different problem.”

Fertiliser harms soil

© Rocky Farms

Mr Rockey also claims synthetic fertilisers are harmful to soils, and in particular nitrogen-fixing bacteria and mycorrhizal fungi.

“The former fix nitrogen from the atmosphere and add it to the soil, while the latter do a great job in mobilising phosphate. The more we rely on synthetic fertilisers, the less we get from this natural system, increasing our dependency on synthetic fertilisers.

The combined effect of these inputs is to destroy soil life, stop carbon cycling and weaken the soil’s structure, he says. “Soil that has a poor structure and is low in carbon has very little pore space, lowering water infiltration and water-holding capacity.”

He believes that when you have poor soil structure there is little space for gases to move in and out of soil, creating an ideal anaerobic environment for pathogens and weeds to thrive.

Weeds are a good indicator for soil health. “When we were farming conventionally, our two main weeds were nightshades and sunflowers, which are an indicator of a tight, waterlogged soil that is low in carbon.”

Mr Rockey changed his approach 20 years ago, initially to reduce operator exposure to chemicals. Managing carbon, however, is at the heart of his biotic farming system. “I’m not organic, but I’m solving problems based on life rather than destruction.”

Rotation

© Rocky Farms

His rotation consists of just two crops – a cover crop and potatoes – grown under pivot irrigation. The cover crop has replaced the usual rotational crop in the area – malting barley – which he found required too much water to grow.

He uses living or biotic inputs to replace the fertility lost with removing harvested potatoes.

“They all either contribute carbon or add to life in the soil.”

Cover or companion crops add carbon to the soil through root exudates or plant residues, which is then used by fungi and bacteria to create energy through respiration, as long as they have access to oxygen. “This is why soil structure is so important. If it is tight with little pore space, oxygen cannot enter the soil.

“After growing the cover crop, I add compost, with soya bean meal and fish, adding extra carbon.”

Manure from livestock that graze the cover crops and biological inputs – known species of bacteria or fungi – also contribute positively to the system.

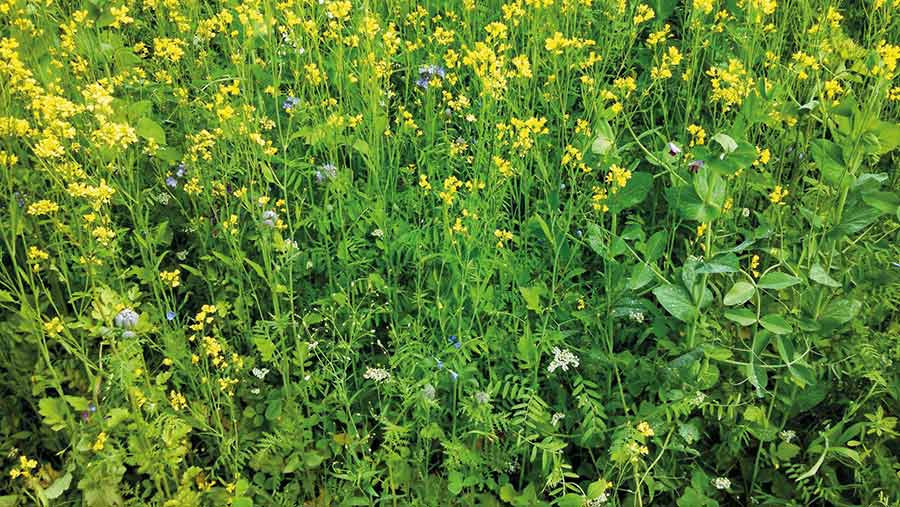

Companion crop

© Rocky Farms

In addition, Mr Rockey grows a diverse companion crop with his potatoes, including legumes to fix nitrogen and buckwheat, which improves the activity of mycorrhizae fungi, making phosphorus more available to the potato crop.

The result has been a system where he adds no synthetic fertiliser and soil that improves its own structure, he says. “The bacteria, as long as they have a food source, build microaggregates, and the fungi come in, along with glomalin, and form macroaggregates.”

That improves the water infiltration and holding capacity, meaning he needs less irrigation for each application and extends the period between applications – important when you’re farming in a desert.

An aerobic soil decreases the threat from disease, while the cover crop mix also helps manage parasitic nematodes through either biofumigant effects or not being hosts.

“Oilseed radishes are a great tool – they encourage the nematodes to lay eggs into the tubers of the radish, but prevent the eggs from hatching.

In addition, he says the life in the soil is very important for managing parasitic nematodes.

No herbicides

Herbicides were the first input to be removed from Mr Rockey’s system, not least because they could sometimes have a direct impact on the crop. “We mostly rely on tillage for our weed management.

“It’s a beneficial tool but you need to be careful with it, as every time the soil is physically disturbed, you can damage the carbon levels in the soil and the soil structure. This is a tool that can be overused.”

The weeds have changed in his system. His number-one weed is red root pigweed, which is an indicator of a well-drained soil with good fertility and high in carbon.

As well as tillage, the cover crop can be managed to reduce weed seed return by earlier termination or grazing by livestock, while beneficial insects also predate on weed seeds.

In a similar way, insect pests are also managed using multiple tools, from beneficial insects encouraged by flowering plants in the system to systemic acquired resistance. “That’s where healthy plants living in healthy soil can fight off attack from insect pests.”

While there was a transition period when first developing his approach, the results have been positive economically. “We’ve been able to maintain our yields while reducing how much we spend, and the quality is the highest we’ve ever had on our farm.”

That includes storage quality. “When you’re throwing less away that’s another way of improving your profit margins.”

© Rocky Farms

UK lessons

So could his system work in the UK? While recognising there are fundamental differences between conditions he faces and ours, including the absence of late blight, Mr Rockey says the way he farms has value.

“I’m not trying to tell you how to farm, but focus on the fundamentals. Regardless of what environment you’re farming in and what outside factors you’re dealing with, you can’t tell me that soil structure, carbon cycling and plant diversity won’t have a positive impact.

He adds: “In your environment, you’re going to have figure out how to apply those fundamentals, but they are strong and universal. I’ve seen them work in enough different places to believe in them.”

In part 2 next week, we delve deeper into the techniques Brendon Rockey uses to control aphids and weeds, and his cover crop management.