How optimistic potato grower targets soil improvements

© Mike Abram

© Mike Abram Potato planting might only have finished in the last week of May, but our Northern Arable Insights grower James Pick is still reasonably optimistic for the crop this season.

“We were around four weeks behind schedule planting, so there’s probably going to be a yield decrease – maybe of 10%,” he says.

“But provided we have a nice summer we should be OK. The fact we don’t have as many potatoes to harvest this year means we can delay starting for a week – I’m hoping that some of the decrease in yield can be covered by harvesting later.”

See also: Variety choice and targeted N are vital for Scottish grower’s potato profit

Target yields for the three varieties, all of which are grown for McCain for either McDonald’s fries or McCain own-brand fries on long-term storage contracts, varies between 45t/ha for Pentland Dell and Royal at 55t/ha, with Innovator at 50t/ha.

“The Royal is contracted at 62.5t/ha, but we’re unirrigated so it’s an unrealistic target for us,” James says.

“On our heavier soils holding more nutrients we seem to be able to achieve over contract tonnage with Innovator and Pentland Dell.”

Area is down to 155ha from 220ha two years ago, reflecting the increased costs and risks from growing potatoes and land availability, despite a relatively healthy increase in contract price from McCain.

“There are some good growers in the local area so there is competition for land. Landowners are looking to move towards more soil health-friendly crops, an extra crop of wheat or barley, while oilseed rape has been a fantastic-paying break crop for a couple of years.”

Aims

Improving soil health and reducing pesticide inputs are key linked aims for James across the near 400ha of cropping, which includes 138ha of land rented for potatoes near Filey in North Yorkshire.

“Any reduction in pesticides is going to come from improving our soils,” he says.

It means taking a multi-pronged approach across the rotation using organic amendments, such as compost and farmyard manures, reduced cultivations, and cover and companion cropping.

For example, cover crops of mustard, oats, phacelia, buckwheat and a legume species, such as a vetch, pea or bean, are planted in late August or early September after wheat harvest to overwinter before the potato crop.

“The roots pump exudates into the soil, keeping the soil biology stimulated heading into winter and early spring,” he explains. “That improves friability and soil aggregation so we can reduce the need for cultivation.”

Where cover crops are grown it usually means ploughing can be avoided. “We desiccate in February, top it, and then go in with a subsoiler, ideally in good time before we want to go in with another cultivation to allow the soil profile to dry a little.”

A Bomford Superflow drag cultivator breaks up any clods left after subsoiling, while a Horsch Terrano creates tilth for the bed-former.

The aim is to avoid a pass with a bed-tiller, although with this spring’s wetter weather that hasn’t always been possible.

“Even so, we’ve decreased the area by at least a half that we have to use it on, and are also going much quicker – 2.5km/h compared with 1km/h so the intensity of the pass is much less.”

On short-term rented land farmyard manure is applied within a week of cultivation – you get more value for your money, James says – while compost tends to be applied on land where the farm has longer term control.

That’s part of the strategy to reduce reliance on applied fertiliser, while increasing the water holding capacity of the soil.

But discussions on his recent Nuffield Scholarship travels investigating whether potatoes can be grown in a regenerative system have brought home the importance of balancing the two organic amendments and cover crops in the system.

“You need three things in your soil – the living, the dead and the very dead,” he explains.

“The living is your green manures or cover crops, the dead covers manures and incorporated dead cover crops, while the very dead are composts that have been through biological processes to break it down and leave a stable carbon source.”

The living and dead parts – particulate organic matter – are relatively easily broken down and cycled in the soil, while the very dead – mineral organic matter – is relatively inaccessible to plants.

As he tries to improve his soils, he says he will need to find the correct balance between composts with manures and high nitrogen cover crops, to both cycle carbon and nutrients effectively while building a bank of more stable organic matter.

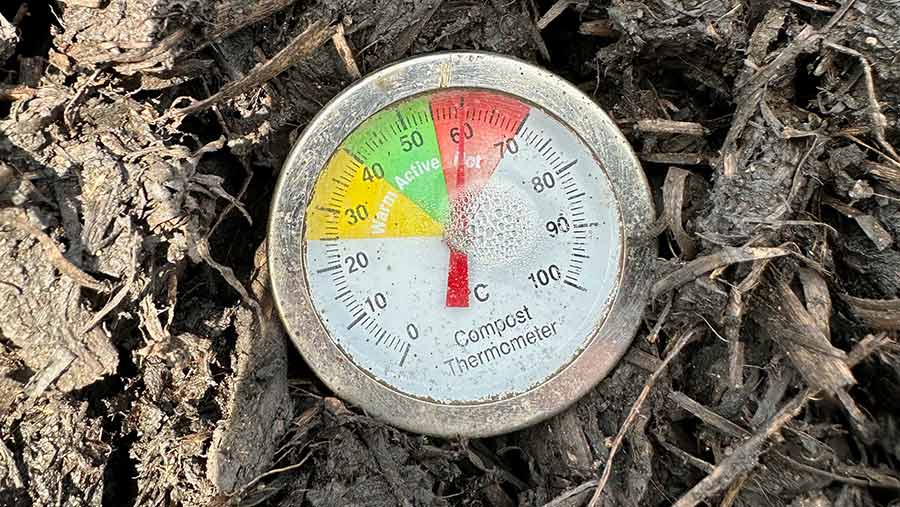

© Mike Abram

Soil carbon

He plans to use NRM soil carbon plus tests to help determine the amount of active carbon in his soils, and inform cover crop management, manure and compost use.

“Historically our soils have had a lot of manures, so I don’t expect the issue to be active carbon and especially now we grow cover crops – it’s going to be building up the bank of stable organic matter over a period of time.”

Another area where James is learning is in reducing pesticides. “Potatoes are the main breadwinner for this business and a high-risk crop, so we’re doing small-scale trials to learn where we can make reductions and where we can’t,” he explains.

“We already use fewer fungicides than many, but it’s mostly down to intuition, so we’re using sap analysis for the first time this season to help make more informed decisions.

“We’re also in one field putting flowering cover crop strips at 30m intervals, and in some other fields putting them in non-planted areas to see how it can help support us in not using insecticides.”

Micronutrition is also being trialled. “We’ve seen the role silica can play in fighting off flea beetle in oilseed rape for the past two years, so we’re going to try it in potatoes, but through the season rather than for any particular pest.”

Silica is the most abundant nutrient in the soil, but one of the least accessible. Applied as a foliar spray, it increases the strength of the cell walls.

That activity was used to replace growth regulators in a crop of wheat with good results last year, he concludes.

Storage challenges

Long-term storage without CIPC (chlorpropham) is a challenge, with alternative products providing mixed results.

The farm has about 8,500t of storage, mostly ambient, but including one store with a two-year-old refrigeration system, which is usually used to store Royal until June with positive results.

That’s contributed to increased energy use, tempered by access to renewable energy from two turbines and some roof-top solar panels. Target storage temperatures are 7-10C.

Ideally, James Pick will use maleic hydrazide as a sprout suppressant and growth regulator in field, but last season’s hot and dry conditions meant it could not be applied to a stressed crop.

That has contributed to higher levels of sprouting in store, James says.

This season ethylene has been tried without a huge amount of success, while the finally approved 1,4-dimethylnapthalene (DMN) has also disappointed with its performance. “We haven’t seen the response other people have, but we’ll look to use it again next year.”

Mint oil, however, has impressed, stopping further growth after the application of DMN.

The loss of CIPC has meant a drastic loss in storage stability, as well as a massive increase in costs from £0.60/t to £10-12/t, James points out.

“We used to be able to store a crop through until June and see only 2.2% weight loss, now it is comfortably in excess of 3%.”

In addition, as the potatoes soften as they sprout, they compact more in the bulk storage leading to compaction bruising and a requirement for the processor to use them within 24 hours once removed from store.