Direct-drilling wheat into clover ley saves farm £100/ha

© Billy Lewis

© Billy Lewis Listen to Richard Allison read this article or see the text below.

Direct-drilling winter wheat into a clover ley to form a living mulch understorey cut winter wheat production costs by £100/ha at Boycefield farm in Herefordshire.

Nitrogen, fungicide and plant growth regulator applications were significantly scaled back when the Lewis family took the plunge to establish winter wheat into an existing 2ha clover ley.

After promising trial results and a successful wheat harvest, Billy Lewis, who farms beef, sheep and arable with his parents, Jim and Lucinda, then planted a crop of winter oats into the mulch. He now plans to scale-up the living mulch area across the 140ha farm, near Dilwyn.

See also: Is undersowing cereal crops with clover the next big thing?

Increase soil biology

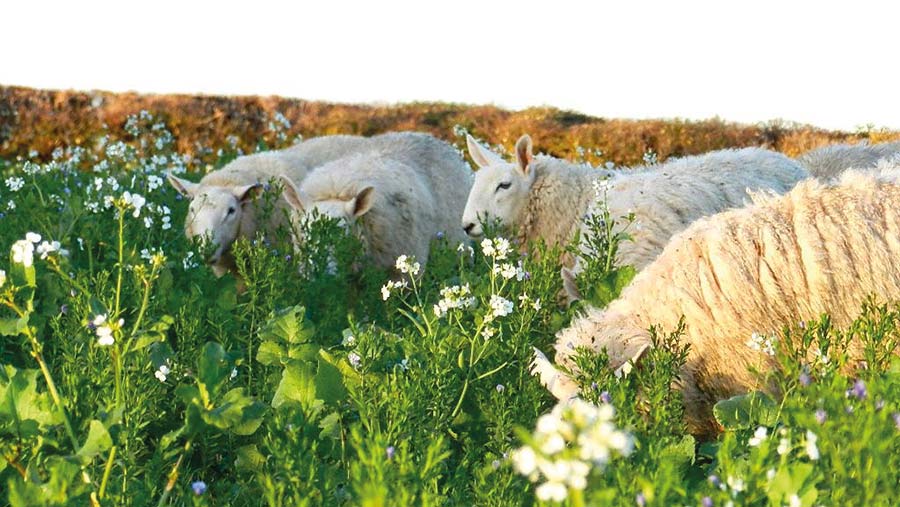

The Lewis family have always aimed to farm simply and sympathetically with nature, making the most of clover and herbal leys to feed their flock of 300 Cheviot ewes and 45 pedigree Hereford suckler cows, which play an integral role in the arable rotation.

© Billy Lewis

Since Mr Lewis’s return from agricultural university two years ago, he intends to expand this further by implementing a completely regenerative farming system.

“The aim is to take every opportunity to increase biodiversity on the farm and get a more biologically active soil so we’re relying less on chemical inputs.

Being a mixed farm puts us in a great starting place to achieve this, where each enterprise can help complement another,” he says.

Insecticides are no longer applied and land is cover cropped over winter, using a seven-way species mix at a cost of £39.60/ha.

This provides additional mob-grazing for replacement ewe lambs, before being sprayed off with a low rate of glyphosate and direct-drilled into.

A six-week catch crop between two autumn cereals also brings further benefits to soil health, costing £29.20/ha.

“Fortunately, we have a local contractor with a direct drill, as they’re not usually commonplace in Herefordshire,” says Mr Lewis.

© MAG/Emma Gillbard

Wheat and clover

The family strived to take direct-drilling one step further, and in the autumn of 2020 decided to plant Costello winter wheat into a 2ha existing two-year-old clover ley.

This enabled them to cut nitrogen rates by 70kg N/ha, reduce plant growth regulator rates by 25% and save on a T3 fungicide spray.

“From spraying off the clover, to harvesting, growing the wheat in the living mulch made an overall saving of £100/ha in growing costs when compared to our standard wheat crop and had no detriment on yield,” explains Lucinda Lewis.

Before planting with the Vaderstad Rapid at a seed rate of 173kg/ha on 11 October, the sheep took a final graze of the ley composed of 80% clover and 20% perennial ryegrass.

This was followed by a reduced rate of glyphosate to remove the remaining ryegrass.

Over winter, the clover had very limited growth and naturally dropped back. Mr Lewis and his parents initially thought the trial had failed due to the lack of clover establishment, but come spring, they were pleasantly surprised with how well the clover had bounced back and wheat had performed.

© Billy Lewis

Nitrogen savings

Due to the nitrogen-fixing clover growing beneath the wheat crop, the Lewis family scaled back nitrogen rates by 70kg/ha to just 100kg/ha, with an additional 6kg/ha of nitrogen foliar spray applied at the T2 timing.

Conventional wheats would usually require a three-tiered fungicide programme, but in the clover trial the all-important T3 timing was dropped. This came with zero yield penalty, yielding 8.75t/ha.

Mr Lewis notes that the living mulch also helped suppress annual weeds such as groundsel.

Blackgrass is not an issue, due to the mixed farming nature of the area, but he talks of a noticeable reduction in the number of thistles and docks, which pose more of a threat.

Despite this, a herbicide application in March encompassing 1.2 litres/ha Hatra (iodosulfuron + mesosulfuron) + 1 litre/ha of the adjuvant Bipower was applied to keep any ryegrass volunteers at bay.

Fortunately, it also stalled the then rapid clover growth that would have otherwise overpowered the wheat.

“The clover really pushed on during the spring, despite very limited growth over winter. If it wasn’t for the herbicide application knocking the clover back, it could have been too strong.”

Harvest

© Billy Lewis

One potential concern of the trial was harvest. Would the clover create difficulty combining? Would the straw become contaminated with green matter? Thankfully, there were no issues at all.

“At harvest, the clover was ankle height, but it cut with ease and we experienced no problems. In fact, we didn’t even raise the stubble height any higher than usual,” says Mr Lewis.

After harvest, compost was then spread onto the living mulch/stubble area, before receiving a dose of glyphosate mixed with fulvic and citric acid.

“In the future we might try grazing the clover really hard prior to planting the next crop, rather than using glyphosate.”

Winter oats

This season, Mascani winter oats are currently growing in the clover mulch and a second field of clover and winter wheat established.

Similar to last winter, the clover died back but Mr Lewis hopes it will spring back into action as temperatures begin to warm up.

“The oats are not as forward as a conventionally established crop, but it’s costing us a fraction of the establishment costs. After all, we’re looking for the highest profit, not the highest yield.

“They were planted at a reduced seed rate of 100kg/ha, but this will, hopefully, enable greater tillering potential of the oats and allow room for the clover to establish once again,” he explains.

He plans to establish a diverse overwinter cover crop after the oats have been harvested for grazing lambs.

Come spring 2023, the field will either be planted to a two-year clover ley or grazable diverse summer cover crop, before returning to winter wheat.

Composting manure at Boycefield Farm

© Billy Lewis

When a friend’s secondhand compost turner came up for sale, Billy Lewis, who farms with his parents at Boycefield, jumped at the chance to purchase it as the farm transitions to a more regenerative system.

All 500t of farmyard manure at the Herefordshire farm is now transformed into compost in a bid to apply a more biologically active food source with readily available nutrients to the soil.

Using the composter, manure is turned five or six times over a two-month period.

Molasses and seaweed extract is added to the mix to provide energy for bacteria, while additions of cardboard and woodchip help encourage fungal populations.

“Applying compost to the arable land is great as it shares similar properties to soil humus, so it rapidly decomposes and is gone from the soil surface within a week of application.

“This means no clumps of manure that can otherwise cause problems when direct-drilling,” says Mr Lewis.

“What’s more, we can assess the nutrient analysis of compost so we know exactly what we are applying,” adds Mr Lewis’s mum, Lucinda.

One potential idea Mr Lewis had was to trial adding clover seed into the compost heap, so that when the compost is spread on arable and grassland, there is a replenishment of clover seed going back onto the land.

Last year, the Lewis family began working closely with a neighbouring farm who had also started the regenerative agriculture transition by setting up a straw-for-compost deal.