How to keep tubers disease-free in potato stores

© Tim Scrivener

© Tim Scrivener Both seed and ware potato growers are urged not to fall at the final hurdle and leave crops vulnerable to storage diseases this year, as field conditions push up the risk of tuber damage at harvest.

Storage diseases can drag down potato crop quality (see “Eight key potato storage diseases”) during the storage phase and are important considerations for both seed and ware producers, but for slightly different reasons.

Potato crops often spend more time in store than in the ground, and in the case of some ware crops, this can reach eight to nine months.

See also: Are no-till potatoes a pipe-dream?

This means there is a much higher probability of things going wrong and storage diseases developing, says SAC consulting potato specialist Kyran Maloney.

“If a store isn’t carefully managed, temperatures aren’t stable and you get condensation developing within the building, there is an increased risk of disease spreading and causing losses,” he adds.

For seed growers, some would assume that risk is much lower due to the shorter storage period, but certified seed is subject to much stricter quality criteria, with tolerance for some tuber diseases very low.

“A seed grower will put huge effort into producing a high-grade product with a low disease burden throughout the season.

“If you then harvest it into dirty boxes and a dirty, poorly managed store, you are potentially going to fall at the final hurdle and not maximise your marketable yield once all the crop is sold,” explains Dr Maloney.

Types of storage disease

Storage diseases broadly sit in three camps. First, there are fungal rots, which include dry rot and gangrene.

Second is the soft rots, which include blackleg, tuber blight and watery wound rot.

Last, there are the skin blemishes such as skin spot, silver scurf and black dot.

It is important to be able to identify each disease, as some have different risk profiles and require different management strategies both during the growing season and in store.

Varietal susceptibility is also a major factor in risk assessments and planning management strategy, with the Potato Variety Database providing information on the majority of commonly grown cultivars.

Dr Maloney says test digs taken throughout summer will forewarn growers of potential issues that might cause problems in stores, and these should be carefully recorded ahead of harvest.

“This will inform how they are managed once lifted. Some problem stocks might be sold straight away, some stored separately, or if a seed crop, treated with a fungicide soon after harvest,” he explains.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that dry rot has been increasing in prevalence over recent seasons and SAC Consulting is working with Certis Belchim and Syngenta to survey the disease and its sensitivity to the two available fungicides.

The survey continues this year and Dr Maloney encourages growers to send off dry rot samples during the new storage period.

However, last year’s examples from submitters were a mixed bag in terms of correct identification, which, as mentioned, is key to improving management.

“Many samples were gangrene, and we received soft rots and tubers with physical damage, too. Identification of storage issues is an area where the industry could improve. Ask your agronomist if you need help.”

Store hygiene

Dr Maloney says the first step in minimising storage disease risk is good hygiene, so when stores are empty ahead of loading, they should be thoroughly cleaned to eliminate sources of inoculum.

Spores can lurk in dust, and when disturbed can infect new crop coming into store. This should be hoovered up and not swept, as sweeping simply redistributes dust around the building.

Boxes can also harbour disease. Keeping them outside after emptying is a good way of reducing inoculum, as ultraviolet (UV) light is effective at breaking down spores and disinfecting the timber.

“A belt and braces approach, often used by high-grade seed growers, is to fumigate stores and boxes using an ozone generator.

“Another option is to use Jet 5 [peroxyacetic acid] through a pressure washer in buildings and boxes.

“If you experience a breakdown of a stock, or a building hasn’t been cleaned for some time, this is a good addition to a control strategy where practical,” explains Dr Maloney.

He adds that regular cleaning of seed grading lines and other handling equipment with Jet 5 throughout the grading process is also good practice, particularly between seed lots, reducing the probability of tubers picking up new infection.

“With ware growers often storing for longer, store hygiene is equally important, and if home-saving seed, any problems in store can come back to bite you the following season,” says Dr Maloney.

Gentle harvest

With tuber damage the easiest route for pathogens to gain a foothold, ensuring that tubers are not scuffed, nicked, or bruised is another important step in minimising losses later.

This year, hot and dry weather has prevailed, and reports of high dry matter content of crops means that risk of bruising is particularly acute, with dry rot the main threat in such a season.

Dr Maloney says before harvesting, it is good practice to carry out a thorough review of the harvest and handling process, including aspects such as harvester condition and setup to ensure tubers are handled with utmost care.

If the dry conditions continue, he also sees many growers irrigating before lifting to ensure the soil provides enough cushioning for tubers as they pass up the web.

Quick and effective desiccation is important and waiting for adequate skin set will help to minimise the potential for damage.

“There is a balance to strike. Sometimes you need to have the crop out the ground by a certain calendar date, but early harvest can increase the risk of dry rot.

“Leaving a long interval between haulm destruction increases risk of gangrene and black dot.

“You need to make decisions on a field-by-field basis and test skin set in multiple places, as it can be variable. We are expecting skin set to be fast this season, which will help,” explains Dr Maloney.

Store control

Following on from good hygiene and gentle harvest and handling, optimising the storage environment from the start helps slow disease development.

With soil and tuber temperatures relatively high this year, pull down – the process of taking field heat out the tubers – will be particularly important, along with adequate ventilation to dry and cure any wounds.

Dry curing with relatively warm and humid air is one of the most effective storage disease control measures, allowing the natural wound periderm to develop where damage has occurred, helping to resist disease ingress.

However, during these processes, Dr Maloney says condensation is the biggest enemy, so ensuring there isn’t a big differential between tuber temperature and air temperature will avoid development of condensation in the store.

“Typically, after curing you’d be taking 0.5C/day out of the crop until you reach holding temperature, which will vary depending on the market.”

Consider tuber treatment

Once all non-chemical and hygiene measures are taken, seed producers can opt to use a tuber treatment to coat tubers in fungicide and reduce disease progression in store.

However, as the available options are not effective against all pathogens, correct identification of problems is vital to ensure they are not applied unnecessarily.

There is no option for soft rots such as blackleg and tuber blight, but dry rot, gangrene, skin spot and silver scurf can all be mitigated with either Gavel (imazalil) or Storite Excel (thiabendazole) or a combination of both.

Dr Maloney stresses that application timing and quality of application is key to getting the most out of the products, with treatments applied as soon after harvest as possible giving best results.

Ideally, this should be within 48 hours of harvest as stocks are split graded into store, ensuring that only the seed fraction is treated. Both products cannot be applied to tubers destined for human or animal consumption.

Application over a roller table with a hooded, twin rotating nozzle applicator, such as a Team CTC2, will optimise coverage and subsequent disease control.

“There are plenty of farms still using static nozzles or rotating discs, but all SAC trial work shows that treating soon after harvest using a correctly calibrated hooded applicator with twin rotating nozzles is the gold standard,” says Dr Maloney.

Product choice

Dr Maloney says product choice is a final consideration and points out that in pervious testing work, some fusarium species that cause dry rot and silver scurf have been found to be insensitive to thiabendazole, so this should be taken into consideration.

He adds that in very high-risk stocks, it is a good idea to use both together, but compatibility when mixing into a spray solution can be problematic and growers should seek manufacturer advice before doing so.

Otherwise, Gavel would be the first choice, as there are no known resistance issues with imazalil from past monitoring.

“We do need to update our knowledge on fungicide resistance in potato storage diseases, but based on what we know, opting for imazalil would err on the side of caution when applying a single product,” concludes Dr Maloney.

Eight key potato storage diseases

Dry rot

Dry rot © Blackthorn Arable/supplied by SAC Consulting

Dry rot is mainly caused by four key fusarium species and infection of tubers occurs via wounds or damage during the harvest and handling process.

Poor skin set is a risk factor for dry rot. Correct calibration of the harvester and care when handling is important for reducing damage.

Curing in (warm) dry conditions can aid wound healing and reduce infection. Some species of fusarium have displayed resistance to seed treatment active thiabendazole. So far, there is no evidence of resistance to imazalil.

Gangrene

Gangrene © Blackthorn Arable/supplied by SAC Consulting

Caused by phoma species, inoculum builds up in the soil around daughter tubers, so early haulm destruction and harvest are helpful in reducing risk.

As with dry rot, minimising damage is critical and curing to heal wounds in (warm) dry conditions decreases risk of infection.

Seed treatments such as imazalil can help, but work as part of an integrated control strategy.

Skin spot

Skin spot © Blackthorn Arable/supplied by SAC Consulting

Polyscytalum pustulans is responsible for skin spot and is found on crop debris and in the dust that contaminates stores.

Varietal susceptibility varies greatly, with some common varieties very susceptible (such as King Edward).

A very long latent period means it can be months before symptoms are seen in store. Infection is greater when cold and wet conditions occur at harvest.

If you know a variety is susceptible, prioritise drying at store entry.

Silver scurf

Silver scurf © Blackthorn Arable/supplied by SAC Consulting

Infection of tubers with Helminthosporium solani can occur both in field and in store. Ways to reduce risk include early lifting and rapid drying.

Once in store, preventing condensation is critical, as this helps spread infection, which can occur throughout the storage period.

Ahead of loading, good store hygiene can reduce the risk of infection in store. If a fungicide is used, it should be applied to seed tubers as soon as possible after harvest.

Store holding temperatures below 4C will slow disease development. Like some fusarium dry rot species, resistance to thiabendazole has been reported for silver scurf.

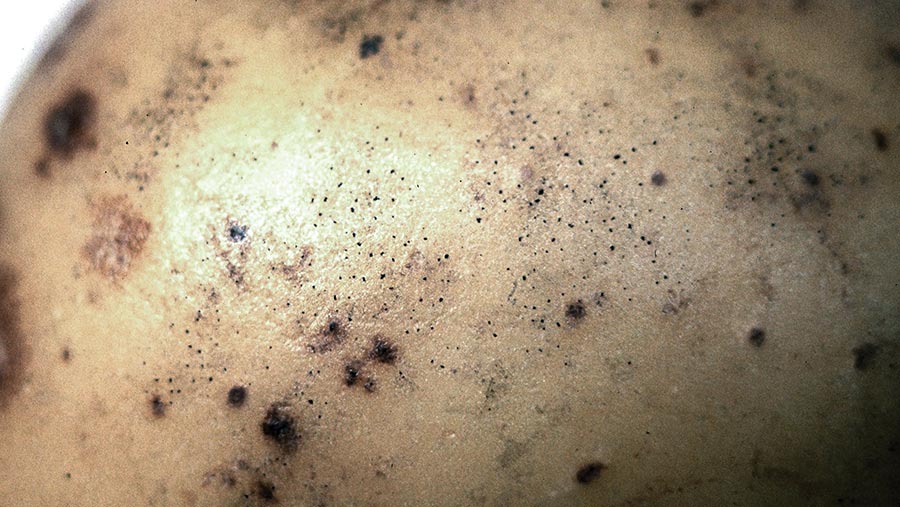

Black dot

Black dot © Blackthorn Arable/supplied by SAC Consulting

The causal agent of black dot, Colletotrichum coccodes, infects tubers in the field and possibly also in storage.

Severity is made worse by tubers being left in the ground, so harvesting early (if possible) helps minimise risk. Thinner-skinned varieties appear to be more susceptible.

Dry curing and temperature control can slow disease development once in store. No storage seed treatment product currently approved in Britain has label claims for black dot control.

Pre-planting seed treatments such as fludioxonil offers reduction in black dot in progeny tubers.

Soft rots

Watery wound rot

Watery wound rot © Blackthorn Arable/supplied by SAC Consulting

Caused by pythium species, there have been increasing reports of the disease in stored tubers over recent seasons. Affected flesh can be discoloured grey to brown with a dark margin.

The rot is moist and quickly liquefies. Cutting open a tuber releases an alcoholic smell, or even fishy if the rot is advanced.

Good store hygiene, lifting early, drying into store and minimal handling will reduce risk. Cooler storage temperatures will slow development.

Blackleg

Blackleg © AdobeStock/Liudmila

Pectobacterium, more commonly known as blackleg, causes soft rots in store.

Symptoms include soft, wet, cream-coloured tissue. Infected tissue is sharply demarcated from healthy tissue and sometimes has darker margins.

Factors in minimising risk are similar to watery wound rot.

Late blight

Tuber blight © Blackthorn Arable/supplied by SAC Consulting

The most important disease in potatoes, it is caused by oomycete Phytophthora infestans, which infects foliage, stems and tubers.

In tubers, symptoms are seen as darkish brown, sometimes purplish, areas on the surface.

The internal rot is a reddish brown, granular rot that is close to the surface, sometimes progressing to the centre. Development is irregular and sometimes thread-like through the flesh.

Tuber blight infection is very serious and can cause whole crop losses.

The skin damage caused by tuber blight allows opportunistic diseases such as bacterial soft rots to invade and flourish.

Good control of the disease during the growing season will minimise risk of development in store and reduce primary seed-borne inoculum in following crops if growing seed.

There are no chemical controls for soft rots or tuber blight once the crop is harvested and in store.