Why biopesticides will play a bigger role on arable farms

© Tim Scrivener

© Tim Scrivener Biopesticides – a group of crop protection tools made from living micro-organisms or natural products – now represent more than 10% of the UK agrochemicals market, with sales growing at a rapid rate of more than 20% a year.

Given a kick-start by the introduction of the Sustainable Use Directive and the need for growers to demonstrate integrated pest management (IPM), they are increasingly finding favour as traditional chemistry is lost, and resistance puts a dent in chemical performance.

See also: How growers will benefit from AHDB’s new variety tool

Good uptake in high-value horticultural and specialty crops has already been seen, where their contribution to IPM programmes and sustainable production is valued.

Success in these markets can be explained in part by the first biopesticides being developed specifically for them, but there has also been greater pressure on these growers to find alternative active ingredients.

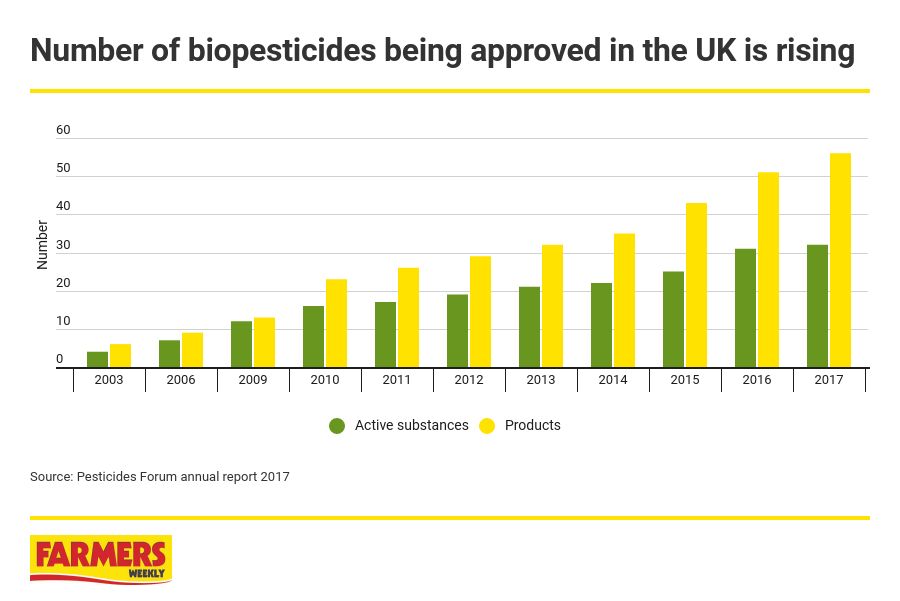

Today, of the approved EU plant protection products on the market, more than 30% are biological technologies. Since 2016, there have been more new applications for products based on biological technologies than conventional chemistry.

“The pace of change has been very fast,” says Roma Gwynn, director of Biorationale and vice-president of the International Biocontrol Manufacturers Association. We’ve gone from having a few niche products to being able to choose from a whole range of authorised biopesticides, with new R&D investment creating an exciting pipeline.”

No longer viewed with suspicion, biopesticides have a range of attractive properties for IPM. However, not everyone is convinced and growers of broadacre crops have been slower to respond.

That could that be all about to change, believes Dr Gwynn. “We’re much further forward than growers think, with effective seed treatments and plant elicitors already available. It’s an exciting time and growers should get involved.”

What are they?

Biopesticides are plant protection products that contain biological control agents. A broad group of mass-produced materials based on living organisms or their products, they divide into three main types, says Dr Dave Chandler of the University of Warwick.

- Micro-organisms Bacteria, fungi, oomycetes and viruses, all of which can be used for the biological control of pests, pathogens and weeds. Examples include the insect pathogenic bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) and the fungus Trichoderma for control of soil-borne pathogens.

- Botanicals Plant extracts with activity against crop pests and diseases. Examples include neem oil as an insecticide, essential oils from citrus for use against both pests and diseases, as well as sarmentine from Indian long pepper, used as a novel herbicide.

- Semiochemicals Chemical compounds produced by one organism to induce a behavioural change in others, either of the same or a different species. Examples include insect pheromones for use in pest monitoring, mating disruption and trapping.

A more recent development is bioherbicides, says Dr Chandler, who says products are on their way based on fungi which can infect multiple weed species.

“Given the problems that we have with herbicide resistance in some weed species, their use looks set to increase.”

How are they regulated?

Just like conventional chemistry, biopesticides must be approved for use before they can be used, sold or supplied. As a result, registered products all have a MAPP number.

Biopesticides: Pros and cons

Advantages

• Little or no residue

• Zero or low re-entry and handling intervals

• Use existing application equipment

• Reduce or stop selection pressure

• Low risk of resistance/tolerance developing

• Good compatibility with other products

• Lower development costs

Disadvantages

• Slower rate of control

• Shorter persistence

• Susceptible to environmental conditions

• Require greater user knowledge

This is different to products sold as fertilisers or biostimulants, which currently do not go through a registration process, even though they may contain active substances.

In the UK, the biopesticides regulation process is governed by the Chemicals Regulation Division (CRD), which stipulates that these products must have supporting evidence that they are safe and effective.

That includes data on familiar areas such as mammalian toxicology, residues, operator and bystander exposure, fate and behaviour, crop safety and efficacy. The latter means there has to be proof of a consistent level of control or effect.

“They are safe and compatible,” says Dr Chandler. “Legislation may have driven their use, but it also governs their use.”

Do they work?

Where they are used against plant diseases, biopesticides tend to be used as preventative treatments and are often applied in an inoculative strategy.

Against pests, they are usually used as curative treatments, with monitoring information helping to make the application decision.

In this situation, the agent is often applied in large numbers to achieve rapid pest control – meaning that persistence is short and the agent has to be reapplied frequently.

In broad terms, growers can expect a biopesticide to give 50-70% control, advises Dr Gwynn, who adds that there are products that can do more.

“Remember that there’s a huge range of products with different modes of action and targets,” she says. “They can be used in various ways, maybe as a second line of defence or supplementary treatment, so their efficacy is sometimes measured differently.

“In general, they’re not as persistent as traditional agrochemicals, so that has to be taken into account with any IPM programme.”

How are they applied?

Most biopesticides can be applied with existing spray or application equipment.

Being based on living micro-organisms and natural products, they tend to be contact-acting. This means they have to be delivered to the right place, at the right time and to the right crop.

“The application equipment is less important than the grower’s understanding of the crop and the disease or pest problem,” Dr Gwynn says.

“If they aren’t applied well and at the optimum time, they won’t work. So it’s down to the users to make sure that they are thinking as biologists, not chemists.”

What about compatibility and restrictions?

Like conventional plant protection products, the advice with biopesticides is to check the label.

They tend to have good compatibility with biological pest control agents and conventional chemicals, so are easy to incorporate into IPM programmes. Most have no harvest or re-entry interval, so they can be used a number of times in the season, according to need.

Some are more susceptible to adverse environmental conditions than others. UV light can be detrimental, while low temperatures can prohibit them from working well.

“The product label gives you all that information,” says Dr Gwynn. “In most respects, any restrictions are the same as with conventional agrochemicals.”

Trials in wheat: Crop Health North

Biological technologies can be used effectively in wheat and will allow farmers to reduce their dependence on conventional chemistry, according to a study conducted by the Yorkshire Agricultural Society’s farmer scientist network, Crop Health North.

The trials set out to discover if conventional fungicides and insecticides could be replaced with biopesticides, either by using them in an IPM approach or in a programme based entirely on biologicals.

The first year’s work was conducted in spring wheat at three sites in the north of England. Three programmes were tested – conventional chemistry, an IPM approach, and biological technologies – with the results showing no difference in yield between the treatments at any of the sites.

In the second year, the work was done in winter wheat.

Two varieties, Skyfall and Leeds, were chosen for their opposing disease resistance profiles, with conventional chemistry again being compared with an IPM approach and a biological programme in six replicates.

The three regimes were as follows:

- IPM Microbial seed treatment, conventional chemistry at high pest pressure, biopesticides at low pest pressure, at standard spray timings.

- Biological Microbial seed treatment, biopesticides at standard spray timings.

- Conventional Chemical seed treatment and conventional chemistry at standard spray timings.

The results were the same as in the first year. There was no significant difference between any of the management regimes, varieties or sites.

In the third year, the work was extended to 0.5ha plots with the three programmes being tested in both high- and low-nitrogen regimes.

This time there were some differences between management regimes recorded in yield, with indications of differences also seen for some quality parameters. Where biological products were used, grain proteins were higher.

The conclusion from the work is that biological technologies can be used successfully in wheat, but several questions remain:

- Would the results have been different/better if the work was done with products developed specifically for the wheat crop rather than for horticulture?

- Would the results have been different/better if application timings and methods were based on biological technologies rather than conventional chemistry?

- Does the uplift in grain protein content mean that there’s interaction with nitrogen inputs?

- Do the costs of these technologies make them economic to use in wheat?

Iodus

One of the first biopesticides to be registered for use on winter wheat is Iodus (laminarin) from UPL.

A protectant, Iodus can be used for the control of septoria triticii, as well as for reduction of powdery mildew.

Known as an elicitor, it stimulates the plant’s own immune system, protecting new leaf, explains Don Pendergrast of UPL, who believes it will have a place at T0.

“It has performed well at this timing and could be an alternative to multisites,” he suggests. “It uses the plant’s own genetic potential by priming it, so that it can stop fungal pathogens.”

Iodus falls into the plant extract/botanical category of biopesticides and is currently being tested on selected farms, with a full launch planned for this autumn.