Arable Horizons: How farmers can help secure water needs

© Jason Bye

© Jason Bye Water availability for agricultural use is forecast to come under increasing pressure as higher demand and climate change put pressure on supplies.

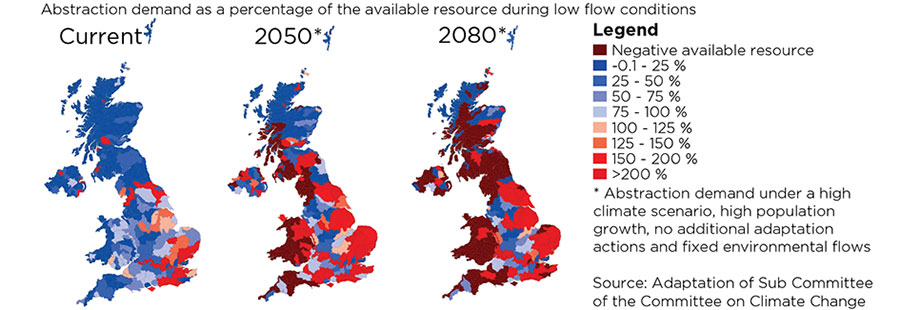

The Adaptation Sub Committee of the Committee on Climate Change has predicted that in a worst-case scenario – where the climate becomes drier, high population growth continues and no adaptation actions are taken – large parts of the UK will suffer massive water deficits (see map below).

Ian Barker of Water Policy international says although the forecast is alarmist, it is also alarming, and action is needed to secure adequate water supplies and to protect the environment.

See also: Why potato growers need to be better prepared for drought

At the end of October this year, some aquifers across the east and south of England were holding “exceptionally low” or “notably low” levels of groundwater for the time of year.

This a legacy of the previous drought during summer 2018, followed by a dry winter, but there are also other factors coming into play.

Water shortages forecast to intensify without action

Prof Barker explains that autumn rains seem to be increasingly delayed and don’t seem to be as effective as they once were at recharging aquifers.

There is also a growing school of thought that losses to ‘evapotranspiration’ – where moisture is lost to the atmosphere through evaporation from the soil or via plants – is increasing and leading to water deficits.

“There isn’t proof of that yet, but work has started to try to better understand how the chalk aquifer will behave in the future in a changing climate,” he adds.

Water resilience – key points

- Climate change, increased demand and environmental issues will put agricultural water supplies under significant pressure

- A joined-up, multisector, catchment-specific approach to water and land management is required to meet this challenge

- Farmers must engage with catchment groups and policymakers to help secure a fair share of water to produce adequate food

- Environment Agency consultation on abstraction reform is now live and farmers are urged to contribute

- Monitoring and recording water use vital to argue case for adequate abstraction volumes once system reformed

Abstraction reform

As part of addressing some of these issues, abstraction licensing is in the process of being reformed, and is the first area that will have a significant effect on growers, particularly in the east and south-east of England.

By 2021, abstraction licences will become environmental permits under new environmental permitting regulations (EPRs), which will essentially bring water abstraction, water discharge and wastewater licences all into one simplified system.

As part of proposed reforms, about 1,500 older permanent licences may be defined as “unsustainable” and about 5,000 time-limited licences can be amended on renewal, or not renewed, without compensation.

One example relates to “headroom”, which is the annual unused volume permitted to be abstracted by the licence holder.

As irrigation water use will vary from year to year, depending on weather patterns and changes in cropping, licences in the current system have a built-in cushion to meet times of increased demand.

If abstractors aren’t using all of their headroom, the Environment Agency will be looking to claw it back and distribute elsewhere – for drinking water, for example – or take it away completely, if abstracting a particular volume poses a threat to the environment.

A government consultation opened in September this year and Prof Barker urges growers to look at it carefully and engage, if necessary, to influence the outcomes ahead of proposed implementation in 2021.

“If necessary, get legal advice in terms of the potential implications for moving abstraction into EPRs,” he adds.

NFU concerns

Paul Hammett, the NFU’s national water resources specialist, is very concerned about the vague phrasing in the guidelines for revoking or changing licences under the new regime.

He says this needs to be tightened up so farm businesses abstracting water have clear guidance on what measures are needed to ensure they don’t lose out.

There also needs to be improvements in the way average farm use and use during dry times is calculated. This will allow regulators such as the Environment Agency to make objective decisions on future EPRs that are acceptable to farmers.

“We must find a satisfactory formula and explanation of how surplus water is actually removed from our licensing system,” he adds.

Mr Hammett sees current academic research and technology playing a key role in helping forecast and monitor future demand at a regional, catchment and farm level. Adequate record-keeping of water use by farmers will be pivotal.

This will also help in long-term planning for securing adequate water resources across a number of sectors, including water companies, industry and agriculture.

Joined-up approach

A multi-sector approach to this long-term water resource planning is up and running as part of Water UK’s water resources long-term planning framework, with the Water Resources East (WRE) programme leading the way.

Covering 31,000sq km from the Humber down to Basildon and across Northampton, the WRE’s area is the driest in the UK, and with high population growth forecast, it is vulnerable to water shortages and extreme weather.

With irrigated agriculture widespread in the region, and some internationally important natural habitats also present, balancing water use in a way that is sensitive to the environment will be a challenge.

Steve Moncaster, WRE programme lead, says the initiative is helping to break various stakeholders out of their silos and get a feel for their wants and needs relating to specific challenges.

These challenges include drainage and flood risk management, the environment, water supplies, transport, housing and farming and food, among others.

The initial process has included a set of priority catchment projects, bringing abstractors, including farmers, regulators and other interested parties together to develop plans at a catchment level.

Technology is then used to gather real-time data on water requirements and potential issues with supply. This helps formulate catchment-specific rules and any need for investment in new assets, such as reservoirs.

Beyond this catchment work, Mr Moncaster says there is also interest in how water management will fit into Environmental Land Management schemes (ELM) as part of the government’s 25-year environment plan.

There could be a huge pot of money for investment and incentives available for landowners to contribute to water management that provides public goods, such as storing water or flood management.

“We think that once you get into this, you’ll expose a whole range of private goods as well. Success is a joined-up approach to land and water management,” he adds.

UK-wide issue

Andrew Blenkiron, estate director at Euston Estate in Suffolk, is engaged with stakeholders across the catchment area and is disappointed how few other local growers or landowners are doing the same.

He encourages farmers to get their voices heard at local and national levels and he warns that the issue of water scarcity is not just a concern for eastern England, with the West also set to see more pressure on water supplies.

As climate change increases the chances of extreme weather, such as drought, there could be problems for irrigators and livestock producers getting access to enough water.

Mr Blenkiron would like to see farmers pressure the government to develop a national drought policy that builds resilience into supplies, with more storage and interconnectivity between water networks to move water to where it is required.

“If those in the West engaged with their local Water Resources Group [WRG], we can get a common cause to develop what we need.

“If these groups don’t get farmer engagement, how are they going to appreciate both aspects of the West needing more water in infrequent dry times and help to make provision for those of us in the East?”

Sponsor’s message

New research is increasingly looking at sustainable solutions for growers to integrate existing technologies and exciting developments into on-farm systems for long-term success.

Driven by growers’ demands to be ever more efficient and the need to make better use of resources, Syngenta is at the forefront of developing practical and proven solutions for farmers and agronomists.

Continued investment and research into smart innovations in products, varieties and support will further improve the precision and performance of future decisions – with many of these new innovations set to be standard farm practice in the future.

Thanks to Syngenta for its sponsorship, which enabled us to run Arable Horizons. Farmers Weekly had complete editorial control of this report.

What is Arable Horizons?

The Farmers Weekly Arable Horizons series, supported by Syngenta, aims to explore tomorrow’s farming technology.

Find out more about Arable Horizons and see previous lectures on the Arable Horizons website.