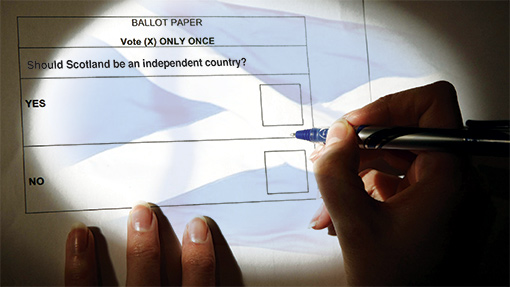

Scottish independence: To stay or to go

With just six months until Scotland votes on whether or not to stay part of the UK, the battle to secure farmers’ votes is intensifying. Nancy Nicolson looks at the arguments for and against.

On Monday evening (17 March), NFU Scotland will host a national debate on an independent Scotland.

The Scottish government’s deputy first minister Nicola Sturgeon and rural affairs minister Richard Lochhead will speak on behalf of the “Yes” campaign and the “Better Together” speakers will include Scottish secretary of state Alistair Carmichael and MEP George Lyon.

What farmers will want to know, above all else, is exactly how independence will affect their businesses.

They feel the same passion and patriotism as the staunchest separatists or unionists, but the message from the industry is that farmers now need the facts on the fundamental issues. Crucially that means clarifying the continuing doubts over the future of EU membership and the national currency that will be available to an independent Scotland.

Around the ring at the mart, at formal debates, in the bar and around kitchen tables, the arguments return again and again to how long it would take an independent Scotland to be formally accepted as a member of the EU. And what options the country would have if the Conservatives, Labour and Lib Dems were to stick to their guns and prevent Scotland from using the pound in the event of a “yes” vote.

While it’s not difficult to find farmers who will talk passionately about the “pros” and “cons” – the two industry action groups, Rural Better Together or Farming for Yes, offer up their versions of the facts – try to track down an agricultural economist for an unbiased analysis, and you’re in limbo.

Scotland’s Rural College and NFU Scotland, usually so keen to punt experts and inform the industry, have declined to comment for fear of appearing to have a political bias.

But Peter Cook, a consultant agricultural economist and former college lecturer, is prepared, at least, to air the key arguments. His view is unequivocal; the CAP and financial support from the EU is the big bugbear.

“The SNP argument is that Scotland’s views and needs are diluted because they’re represented in Europe by DEFRA, which has to make policy fit for Scotland, England, Ireland and Wales. But whether Scotland, by going it alone, could influence European policy more as one small country among many is a moot point,” he states.

The SNP says independence would rocket Scotland from the bottom of European rural funding tables to a seat at the top table for the next round of CAP negotiations. The UK government counters that while Scotland might have secured a bigger share of farm payments if it had been independent, the gain would have been more than offset by the loss of the UK rebate from EU budget contributions.George Lyon, the former NFUS president turned MEP who leads the Rural Better Together team, branded the SNP’s argument that Scotland could “slip in” to the EU within 18 months as “fantasy politics”.

“All the opt-outs the UK currently enjoys are bitterly resented by other countries,” he said. “Negotiations will be protracted.”

Mr Cook says the industry is also looking for clarity on economic policy and currency. “Farmers want to know about interest rates and the economic conditions that would prevail in an independent country. If Scotland had to use the euro, economic policy would be determined in Brussels or Frankfurt. Would that be appropriate for Scotland?

“Markets are also a big worry because Scotland exports most of its surplus to England. If England used sterling and Scotland was using the euro, trade would be affected by currency shifts.”

Meanwhile, Scottish farming and the reputation of Scottish produce is riding high.

Food and drink exports have grown 52% since 2007 and the “yes” camp have the advantage of a popular rural affairs minister in Richard Lochhead, who has engaged with the industry since the SNP government came to power seven years ago. Few would argue his administration has been generous to the rural sector, and English farmers have looked enviously over the border.

Mr Lochhead highlighted the own goal scored by DEFRA minister Owen Paterson, who chose not to hand over the entire €223m (£180m) of CAP convergence money to Scottish farmers, even though it was given in recognition of Scotland’s low payments.

He told his audience: “A vote for independence in 2014 will come at a critical time for the farming industry.

“That CAP convergence money will start arriving in the UK in 2015. But with a vote for independence, it will be completely unjustifiable for the UK to retain this money. Without Scotland, they’ll no longer meet Europe’s criteria for getting that money. But we will.”

Monetary matters aside, there’s also an undercurrent to the independence question that strikes terror or excitement in rural circles, depending on whether you’re a landlord or tenant.

Land reform has rarely been off the SNP agenda and the re-emergence of the debate over a farm tenant’s Absolute Right To Buy (ARTB) are hints that in terms of land ownership, an independent Scotland might be a more reactionary place. Historical resentment over the Clearances and the landed gentry still lingers in large swathes of the Highlands and in parts of the Central Belt.

Mr Cook agrees. “Some of the policies that are mooted by the SNP have nothing to do with practical agriculture but are about righting old wrongs. It’s a slightly dark and nasty undercurrent and there are some landowners and farmers who certainly would worry about that.”

There’s still time for the questions that trouble farmers to be answered and demand for information is high.

NFUS says more than 200 people have applied for tickets for its debate next week, but polls at other recent agricultural debates indicate many minds are already made up.

After an event at Kirkcaldy in February, an exit poll showed that of the 62 votes cast, four favoured independence, 48 voted for staying together and 10 were undecided. At an earlier Young Farmers debate, 11 voted for independence, 38 for staying together and there were 28 abstentions.

Few farmers are coy about their intentions on 18 September, but John Cameron, a respected NFUS president from the 1980s, is playing his hand unusually close to his chest. He’s been a fervent supporter of the SNP government in recent years but insists he’s still weighing up the pros and cons of independence.

“I’m still listening to the evidence and deciding whether independence will be good for Scottish agriculture, and I’m firmly on the fence,” he says. “Which is where all good people should be at this time.”

Daye Tucker runs a mixed farm enterprise near Stirling. The farm supports sheep, poultry, an equine business, fishing, shooting and mixed forestry. She’s on the Board of Scottish Land and Estates.

“As a Scottish Enterprise rural leader and a new entrant into farming in 2000, I have been involved in and witness to the political dynamics that shape Scotland’s farming, rural communities and our environment.

“I first became aware of the importance of the Brussels influence when our group was told by our host at Westminster that of the three political arenas, only two were worth our while trying to influence. Those two were Brussels and Holyrood, with the former shaping the rules.

“Whether pro- or anti-Europe, the Brussels influence has always been there to be managed and influenced for our benefit using negotiating procedures.

“Westminster has a record of failure to negotiate. Successive UK DEFRA ministers have failed Scotland’s fishing and farming industries.

“Agriculture has never been a priority for Westminster when negotiating in Brussels. It is a small percentage of UK GDP. Global availability of imported food has always been the preferred option to domestic supplies.

“Westminster’s disrespect and disregard for Scotland’s farmers, fishermen and rural economy is why I see no future in its continuing rule. It is a political union that has long been crumbling and is now fatally broken. The “great” has been crushed out of Britain by a culture of corruption, lack of vision and moral leadership.

“Scotland has an opportunity to show the way, to do things differently, to start afresh and to lead the way to a fairer, more inclusive future.”

Peter Chapman farms 1,000 acres in Aberdeenshire. He grows cereals, runs a suckler herd and rears day-old chicks to point-of-lay pullets. He has also invested heavily in renewable energy and has four wind turbines on the farm. He is a former NFUS vice-president.

“I have no doubt that our industry is best placed to succeed in the future as part of the UK.

“The UK, along with Germany and France, is one of the three most influential members of the European Union. This means we don’t just sit at the top table, we help make the decisions that affect so many aspects of our industry here in Scotland.

“For all the nationalist claims on the EU, they know that in recent years, farmers in Scotland have received an average EU farm payment that is five times the European average and £8,000 higher than that received by farmers in England. We only get these benefits from being part of a bigger country with real clout internationally.

“As part of the UK, we have open access to a home market of more than 63 million potential customers. There are no regulatory barriers when it comes to selling our produce anywhere in these islands and, crucially, we all use and trade in the same currency. Separation could put all this at risk.

“I cannot see how putting up a border between us and our biggest and most profitable trading partner would be good for business.

And having to deal with exchange rates on top of two sets of regulation when selling to our biggest market, would be a hammer blow to the Scottish farming industry.”