Platinum Jubilee: The ‘Queen’s Men’ and their farming legacy

© MAG

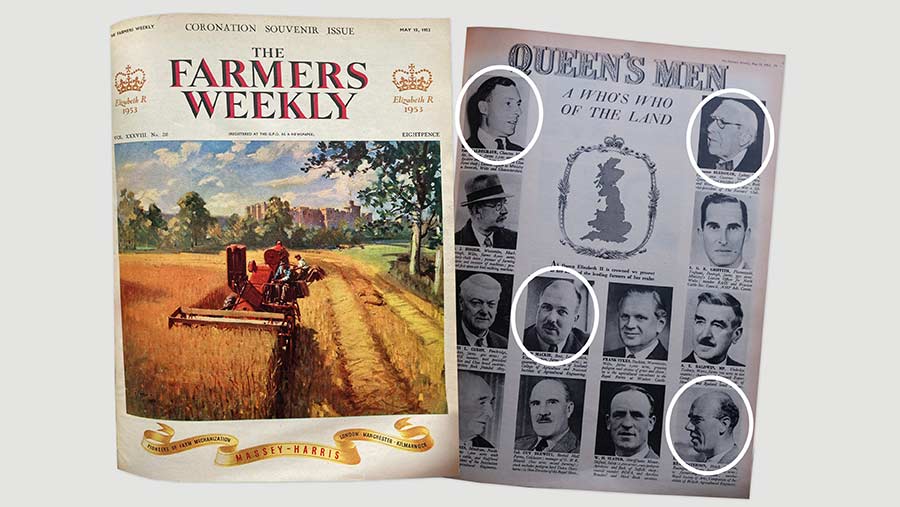

© MAG In May 1953, just ahead of Queen Elizabeth’s coronation in Westminster Abbey, Farmers Weekly celebrated the occasion with a feature called “Queen’s Men”.

In a mood of patriotism, the magazine proudly presented to Her Majesty “some of the leading farmers of her realm”, with a snapshot of 12 of the leading lights in British agriculture at the time.

Unsurprisingly, those leading lights have long gone out. But for some, their legacy lives on, and Farmers Weekly has tracked down four descendants who continue to farm to this day.

See also: Village creates bale art to celebrate Queen’s Platinum Jubilee

Geoffrey Waldegrave

Commanding the title of the 12th Earl Waldegrave, Geoffrey Waldegrave was a hereditary peer and well-known agriculturalist based at Manor Farm in Chewton Mendip, Somerset.

He studied land management at Trinity College, Cambridge, graduating in 1928, and is described by his son William Waldegrave as a “serious and progressive farmer” who devoted his life to agriculture.

At the time he was mentioned in Farmers Weekly, his farming estate ran to 444ha and included Aryshire and Shorthorn cattle, as well as Clun Forest sheep.

The business also had a successful cheddar cheese operation – Chewton Dairy Farms – and a pig unit to utilise the whey.

But it was in public life that Geoffrey really made his name. Shortly after the Second World War he became chairman of the Agricultural Executive Council, and later a member of the Prince’s Council of the Duchy of Cornwall.

Then in 1958, he was appointed junior minister for agriculture – a position he held for four years.

“He would never have called himself a politician,” says William, now Lord Waldegrave of North Hill, who was himself farm minister in John Major’s government in 1995.

“He was an agricultural expert and was appointed to the ministry as such. He would never have taken a job in any other department.”

William is now a director of Waldegrave Farms, renting some 250ha from his elder brother in Somerset, running an organic dairy herd, with all the milk sold to Omsco.

“When my father handed the business over, about five years before he died in 1995, we decided to go organic, because we had lots of grass and lots of space – some of it on top of the Mendips.

“It’s not prime land, so it seemed logical to farm it extensively.

“We only have black and white cattle now, though I do remember the Ayrshires and Shorthorns,” he recalls.

“Dairy farming is an extremely difficult business, but I want to keep it going, partly because I believe in it and partly in honour of my father.

“I’m a less ‘hands-on’ farmer than he was, but we’re now in the process of rebuilding the dairy and the cowsheds, so I think my father would be proud of us.”

Rex Paterson

Dairy farmer and inventor Rex Paterson was a pioneer of the mobile milking bail system first developed by Alan Hosier in Hampshire in the 1920s.

Rex was extremely successful, using the system to produce milk from grass, and he was able to expand his dairy business rapidly.

He rented a number of farms in Hampshire and went on to buy eight or nine farms in Wales, first in Carmarthenshire and then around the coast of Pembrokeshire.

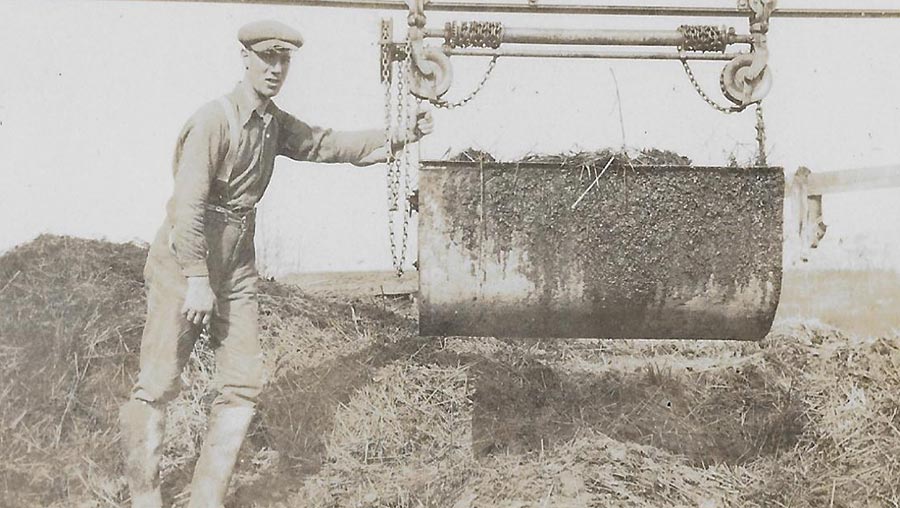

Rex Paterson in Canada © Paterson family

By 1942, Rex was farming more than 4,000ha, and by the early 1970s he had between 3,500 and 4,000 cows, split into small herds of 50-80 so they could be easily managed by one herdsman.

Rex’s dairy empire was scaled down significantly following his death in 1978, though today, his grandson, Douglas, is still milking in Hampshire and Wales.

He is based at Upper Cranbourne farm, north of Winchester, which he bought in 1995 and was one of the farms Rex had rented.

“As a farmer, he was a self-made man,” says Douglas. “He started with very little and built up through hard work and persistence.

I am constantly impressed with his energy and bravery, striking out, taking huge risks and having it pay off. It has got to be an inspiration to anybody.”

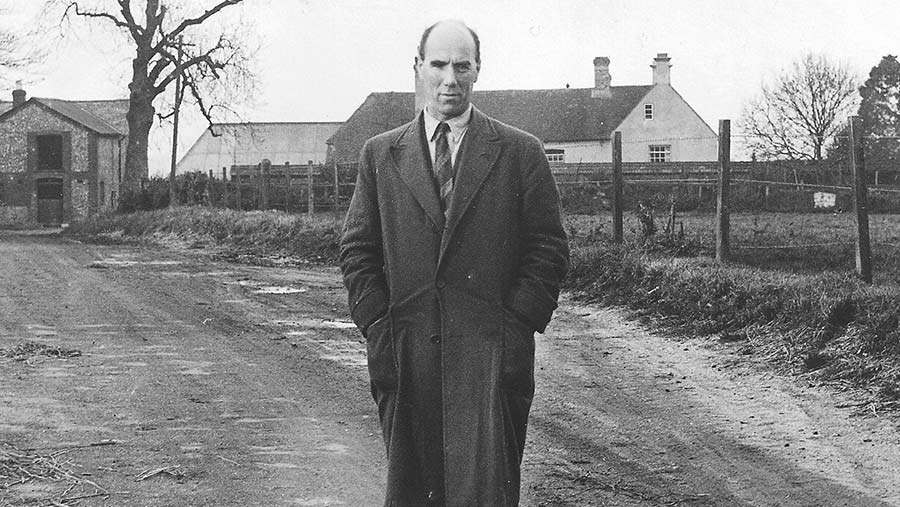

Rex Paterson © Paterson family

Douglas has four herds, 200 cows in each, across four farms – two in Hampshire and two in Wales.

“The farms in Wales are more along the lines of what Rex would recognise and appreciate.

“I don’t think he would approve of the way we milk cows in Hampshire, which is fairly high input, based on maize and bought-in feed.”

Douglas says his grandfather probably picked up his engineering and inventing streak from his uncle, the aviation pioneer Sir Edwin Alliott Verdon Roe.

Rex was a pioneer of silage-making and worked with agriculture engineering company Taskers of Andover to invent the Buckrake (long-toothed rake for gathering grass), and the Fertispread (one of the first rotary spinner fertiliser spreaders).

John Mackie

Born in Scotland in 1909, John was farming about 1,400ha in Laurencekirk, Kincardineshire at the time of the Queen’s coronation in 1953.

John was an innovative farmer, championed the importance of agriculture to the economy, and always believed agricultural land should produce as much food as possible.

Ever since he visited Glasgow in the 1930s, when he saw children with ricketts while they were pouring milk down the drain in Aberdeenshire, he believed in a planned economy and thus became interested in politics.

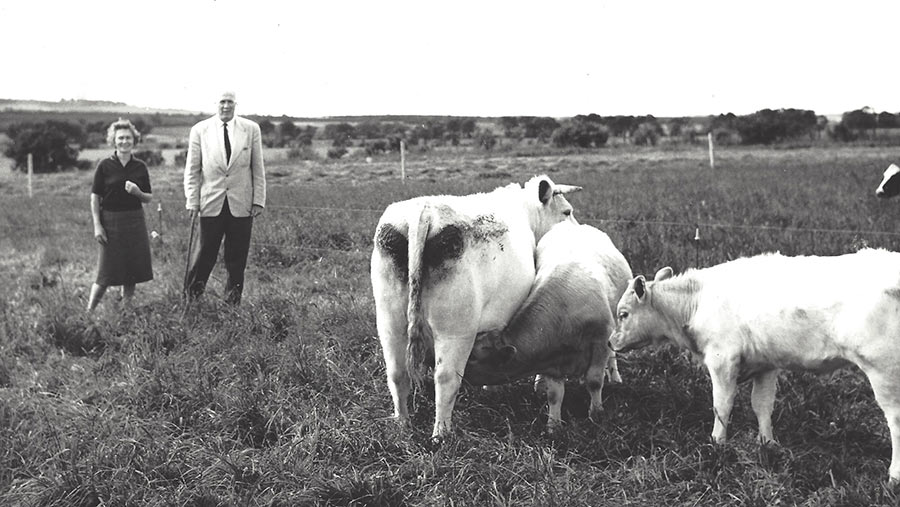

John Mackie and wife Jeannie on farm © Mackie family

He was elected Labour MP for Enfield East in 1959, and bought Harold’s Park Farm in the village of Nazeing, 10 miles from his constituency, where he and his wife, Jeannie, enjoyed entertaining hundreds of his constituents.

John was parliamentary secretary at the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food in the Labour government of 1964-1970, where his farming knowledge was desperately needed.

He became chairman of the Forestry Commission and later went into the House of Lords to be a working peer, speaking about agriculture.

John (whose elder brother Maitland was the man behind the Mackie’s ice cream business), was succeeded at Harold’s Park by his son, George, along with his wife, Catherine MacLeod.

George quickly realised the need to diversify on the 200ha farm, establishing a successful do-it-yourself livery yard, and growing Christmas trees.

George died in 2020 and, since then, Catherine and their son, Hector, have been running the farm. “I remember John very well,” says Catherine.

“He loved farming and loved living on the farm. He remained interested in new ideas all his life. He enthusiastically planted trees and it was fitting that when he died his coffin was made from oak grown on Harold’s Park.”

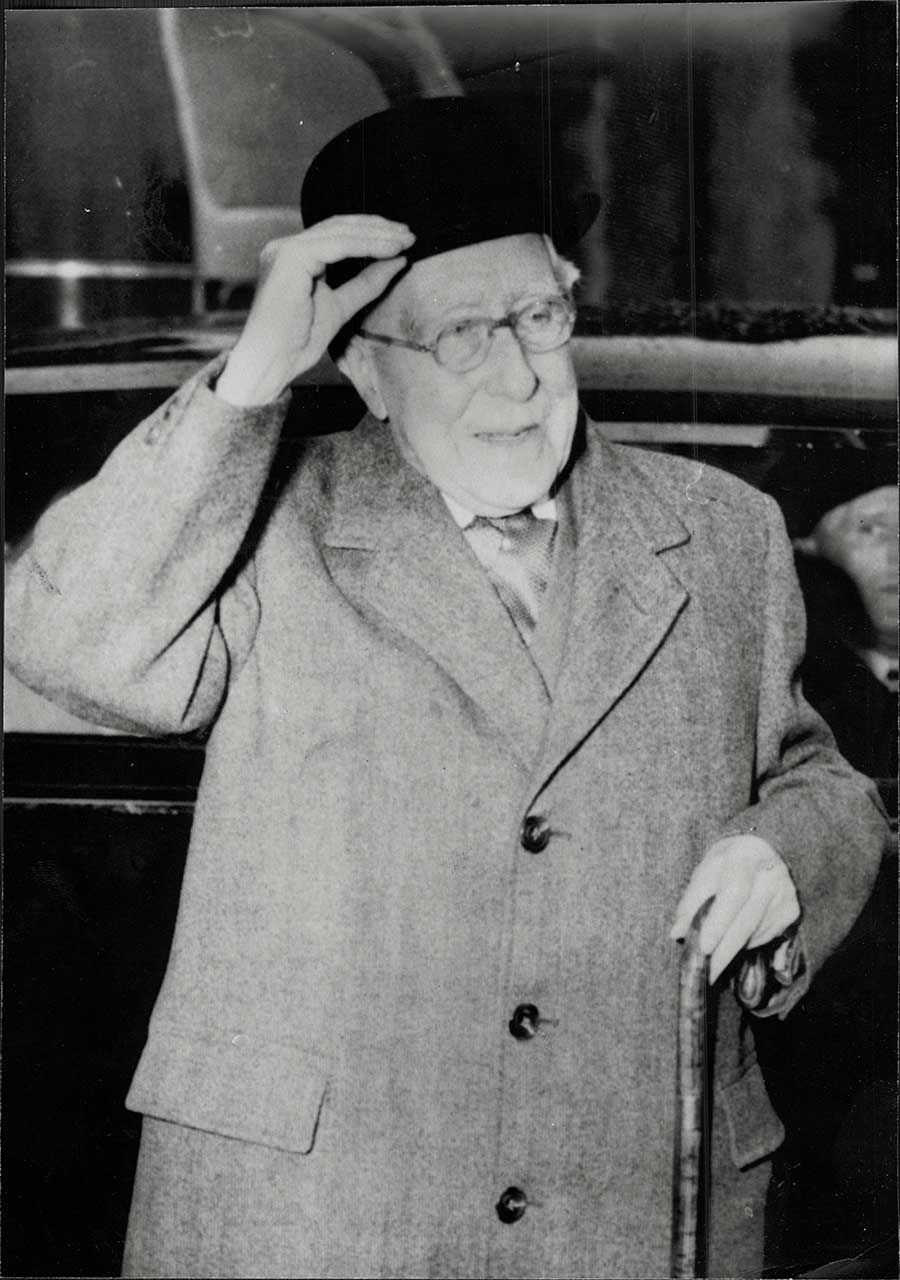

Viscount Bledisloe

Charles Bathurst, the 1st Viscount Bledisloe, was parliamentary secretary to the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries (1924-1928) and had close ties with the Royal Agricultural College (RAC) at Cirencester, which is now the Royal Agricultural University (RAU).

He was born in 1867 and died in 1958, five years after the Queen’s coronation.

Charles was a student at RAC and went on to become chairman of the college’s governing council from 1919-1929, steering the institution during a difficult post-war period.

Viscount Bledisloe © Taylor/ANI/Shutterstock

RAU remembers him to this day, by awarding the Bledisloe Medal for agricultural excellence each year. One of the main student accommodations is also named after the viscount.

In 1935, Charles was made Viscount Bledisloe for his services as governor-general of New Zealand.

He married Bertha Susan and they had three children: Benjamin Ludlow (2nd Viscount Bledisloe), Ursula Mary and Henry Charles Hiley.

The Bathursts own Lydney Park Estate, about 1,200ha of land between Gloucester and Chepstow in the Forest of Dean, where Gavin Green has been working since 1986 and is now the estate manager.

Gavin says Charles was keen on agriculture, and farming remains an important part of the estate today.

“We are milking 850 cows on a grass-based system, twice a day. We’ve had beef, sheep and arable crops over the years, but now it is all grass and dairy.

“In the time since I’ve been here we’ve concentrated on the dairy. The milking platform the cows are on is around 750 acres and then there’s another 500 acres of youngstock and silage ground,” he says.