Opinion: Strike action not an option for disgruntled farmers

© Shawshots/Alamy Stock Photo

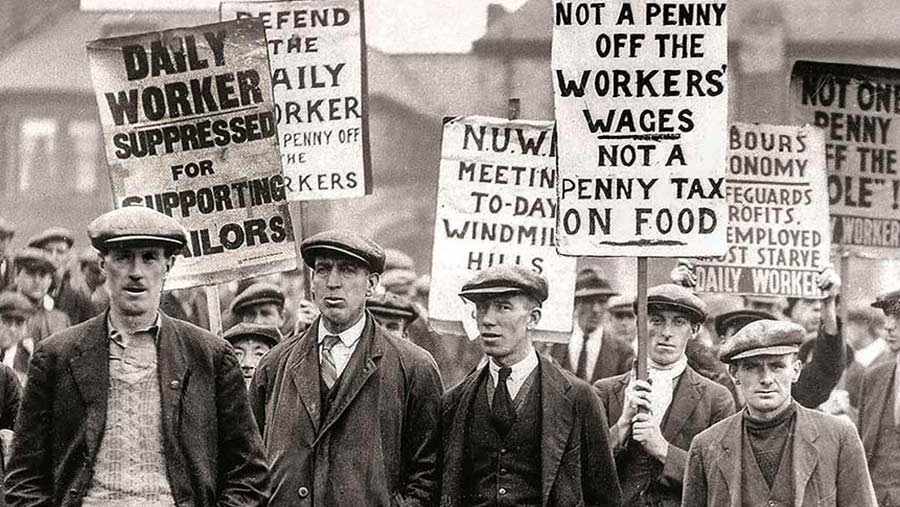

© Shawshots/Alamy Stock Photo Like the return of some ghoul from troubled times past, the news bulletins seem to be full of strikes and threats of industrial action.

It has even been mentioned that farmers should consider some sort of strike action, although this sentiment rather misses the point that strikes are essentially disputes between employers and employees over pay or working conditions.

See also: It’s not just farmers who are feeling the squeeze

As employers, farmers wouldn’t be helping their cause if they decided to down tools, any more than if shopkeepers decided to close their doors until their demands for improved sales figures were met.

It should be remembered here that, in the past, farmyards have witnessed industrial action, but by farm staff rather than by farmers.

A hundred years ago, farmworkers were significantly unionised, in the form of the National Union of Agricultural Workers (NUAW), which at its peak boasted more than 100,000 members.

The 1920s saw a number of bitter strikes over low pay.

But the number of strikes and the power of the NUAW waned with the advent of the Agricultural Wages Act in 1924, whereby farmworkers’ wages were decided by government rather than through industrial disputes.

The last strike by farmworkers was in the mid-1970s, but was for only one day and was a mild-mannered affair.

In his memoir, Henry Plumb, who was the NFU president at the time, recalled that his head cowman advised him the day before the planned strike that he intended to stage a walk-out, but would come in early to get most of his jobs done beforehand.

Since then, agriculture has not witnessed major industrial action.

Although strike action is the weapon of the employee, not the employer, the idea of collective action is not a complete non-starter for the farming community.

It is an idea buoyed by the fact that farmers do have unions, such as the NFU and NFU Scotland, that represent the majority of commercial farmers.

But, while they are unions by name, by law they are technically employer organisations or trade associations. They are not unions that carry out collective bargaining for their members.

The NFU has flirted with collective action in the past. In the 1970s it suggested its members have action days, where no one took animals to markets, in the hope it would improve prices. It wasn’t successful.

It was also a reminder that such actions would lay the NFU open to prosecution from the competition authorities or civil legal action from others in the food chain.

Perversely, one of the NFU’s weaknesses is that it sits on millions of pounds of assets, largely in the form of real estate, that can make it vulnerable to legal challenges – the first rule of litigation being that it is best to pursue those wealthy enough to be worth suing.

It is one reason the NFU has always been wary of too much militancy in its ranks.

At the end of the day, as an individual, any farmer has the prerogative to withdraw their services in response to poor returns by doing nothing.

That, of course, is the function of the market. The problem is that, when markets fail (as we’ve seen recently with eggs), the outcome can risk food shortages.

For those of us who can remember the 1970s, the phrase “a winter of discontent” has unpleasant connotations for 2023. Happy new year…