FW Opinion: Discontent runs deep as margins feel the squeeze

© Keystone Press/Alamy Stock Photo

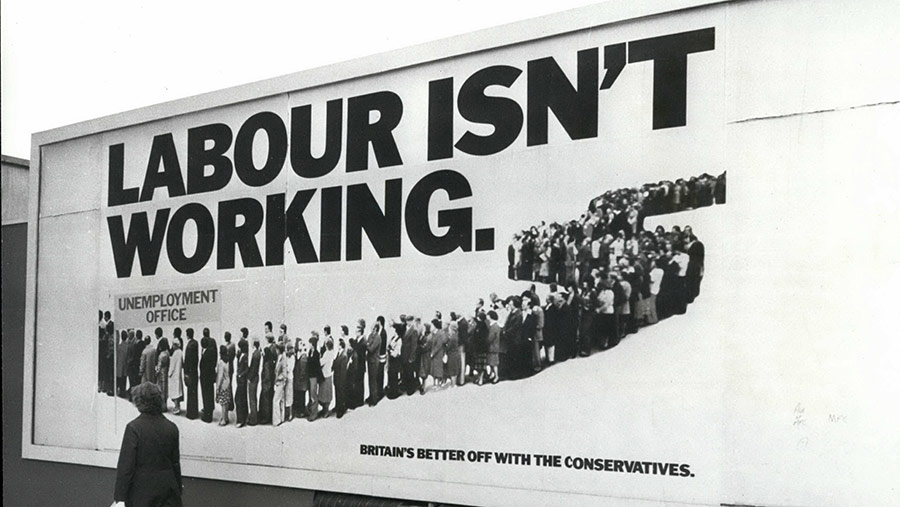

© Keystone Press/Alamy Stock Photo Is the summer of 2022 really shaping up to be “a summer of discontent”?

It certainly feels like it. A series of national rail strikes is already under way, bringing widespread disruption to hapless commuters (and intense annoyance to Jacob Rees-Mogg, as more workers find another good reason to work from home).

See also: Young job seekers have negative image of farming

Heathrow Airport baggage handlers have also voted to strike next month, while teachers, doctors, nurses, firefighters and postal workers are all considering it.

Criminal barristers staged a walkout this week in response to inadequate pay in the face of rampant inflation.

The discontent runs pretty deep in agriculture too. Obviously, farmers do not have the same opportunity to strike (though the effect would be pretty immense if they did).

But results from the NFU’s latest intentions surveys reveal that farmers too are facing a “crisis of confidence”, as input cost inflation undermines their willingness to invest.

According to the surveys, one-third of arable producers have changed their cropping plans in response to rocketing fertiliser costs, while another 840 milk producers (7%) are set to leave the sector in the next two years.

Meanwhile, the National Pig Association estimates a 15-20% reduction in the national pig herd this year.

With ag inflation now running at 25%, according to the latest Andersons data, it is easy to understand why.

Many farm businesses are feeling a severe squeeze on margins – especially in the livestock sector – and with further deep cuts in direct payments to English producers pending, things will only get tougher.

The labour situation also continues to be challenging.

The cross-party Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Efra) committee has repeatedly warned the government about the damage being done to agriculture by its failure to address the shortage of workers caused by Brexit and the Covid-19 pandemic.

Defra and the Home Office seem happy to shrug their shoulders, save for a few piecemeal measures that do little more than paper over the cracks.

The government’s line is that domestic labour should fill the vacancies left by departed EU workers or, failing that, technology will provide the answer.

The folly of that argument is well demonstrated by this week’s survey from McDonald’s, which shows that most young people are turned off a career in agriculture by their poor perception of the industry.

Robotics solutions, too, are a long way off, with a plethora of technical, practical and regulatory challenges to overcome before they can provide even a partial solution.

So what can be done? Yes, there is a certain amount that farmers can do to help themselves.

It’s not all about wages.

Things such as more flexible working arrangements, raising a farm’s social media profile, better communication, and providing training can all help in terms of recruitment and retention.

But, with such a large hole to fill, the government must play its part too.

A far more robust immigration policy is needed – one that lowers the hurdles of recruiting from overseas, contains the costs, and adds certainty for both employers and employees.

The term “summer of discontent” is derived from the infamous “winter of discontent” in 1978-79, when the country was brought to its knees by soaring inflation, widespread strikes, energy rationing, and trade unions at loggerheads with the government of the day.

The upshot of all that was a change of government. Judging by recent by-election results, might history be about to repeat itself?