First World War Armistice 100th anniversary: Farming’s role

Farming played a crucial role in the First World War, but its achievements are often overlooked in history books.

We look at how the war affected farmers in Britain and farming behind the front line in Europe.

Food supply

The agricultural sector experienced unprecedented changes during the First World War and faced the intimidating challenge of producing more food or risking Britain being starved into submission.

Since the agricultural depression of the early 1870s, Britain had become increasingly dependent on overseas countries for staple foods such as wheat, meat and sugar.

At the outbreak of the war, Britain was relying on imports for over 60% of food supplies; 78% of wheat, 40% of meat and almost all sugar was imported.

More than half of all sugar supplies came from Germany, and the nation was also reliant on fuel, fertilisers and feed imports.

© CBW Alamy Stock Photo

The government looked to the USA, Canada, New Zealand, Australia and South America for imports, with transport routes from Europe essentially closed.

The Board of Trade’s figures show a 61% increase in food prices between July 1914 and July 1916. A Food Controller was appointed to intervene with food distribution.

Disaster struck in 1916 when the poor weather conditions resulted in a calamitous wheat harvest.

The British people found themselves left with only six weeks’ worth of wheat.

The Royal Commission on Wheat Supply was formed in October 2016.

It estimated that 100 acres of wheat would support 208 people a year through the production of bread, whereas 100 acres of pasture would support only 40 people a year with beef or mutton.

Livestock production was therefore curtailed by the state, though milk production was prioritised, and guaranteed prices for oats and wheat were introduced under the Corn Production Bill in an attempt to stimulate arable production.

The Board of Agriculture’s contract paid more than twice the price of oats in the pre-war days.

In 1917 Germany declared open warfare on the Atlantic Ocean. Submarine warfare increased and one out of four ships was sunk.

This reduced the supply of sugar by almost 20% and potatoes by 16%.

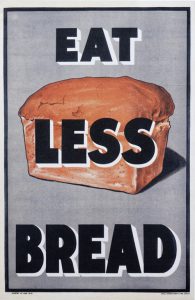

The government introduced compulsory rationing and penalties for wasting food deemed fit for consumption. By 1918, sugar, tea, butter, margarine, bread, meat and flour were all rationed.

Farmers and landowners responded to the appeals for greater output of human food and by 1918 nearly nine million acres had been planted with grain and potatoes – the largest harvest within living memory.

Labour force

More than 170,000 farmers fought in the trenches and up to half a million farm horses were requisitioned by the War Office to help at the front line.

Faced with this labour shortage, farms had to adapt the way they worked to meet the food production challenge.

Often soldiers with experience of operating steam ploughs were called back from the front and soldiers on leave were encouraged to assist with ploughing.

In January 1917, the Food Production Department was created and made responsible for supplying labour, fertiliser and machinery to farmers.

© Associated Newspapers/REX/Shutterstock

One solution was the creation of a training scheme for women in farm-based work by the Board of Agriculture at colleges across the country, resulting in the formation of the Women’s Land Army in 1917.

The wage started at 20s a week, and rose to 22s 6d after three months’ service, and 25s after six months.

By 1918 nearly 8,000 women were working in the Land Army.

© Universal History Archive UIG/REX/Shutterstock

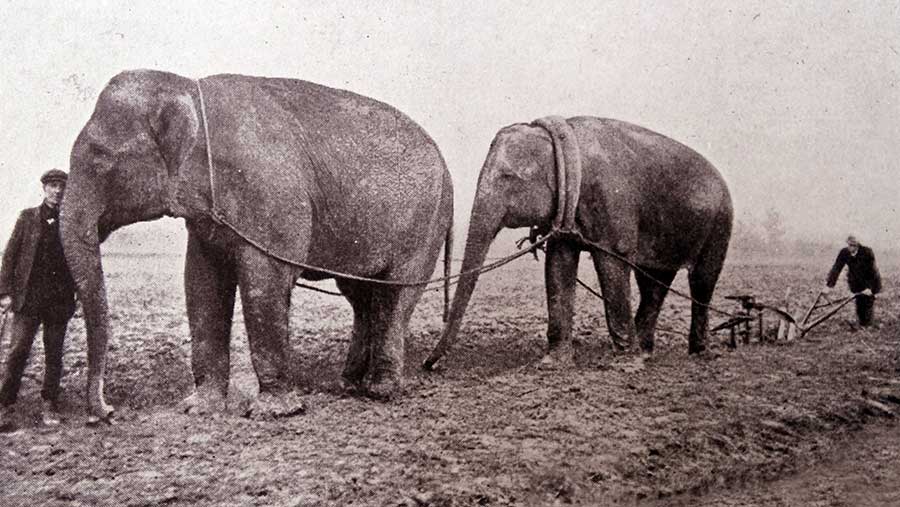

Circus elephants replaced farm horses and German prisoners were supplied by the War Office for farm labour under armed guard.

The prisoners provided substantial assistance to the British food production programme, perhaps most importantly in providing ploughmen.

A farmer and POWs working on his land © Military History Collection Alamy Stock Photo

By the end of the war, the number of prisoners working in agriculture was almost double the size of the Women’s Land Army.

The first recorded survey in February 1918 stated 4,279 prisoners were working in agriculture, but shortly before Armistice more than 30,000 were engaged.

In numbers: First World War agriculture

- 6 weeks’ worth of wheat Britain left with after disastrous harvest in 1916

- 2 million acres increase of land in production by 1918

- 9 million acres planted with grain and potatoes

- 250,000 women working in agriculture by 1918

- 86% rise in expenditure of average family from 1914 to 1918

- 30,405 agriculturally-employed prisoners by 3 November 1918

- 20s/week Women’s Land Army’s initial wage

- 100 pigs/week put through slaughterhouses at military units behind Front Line

- 4,688 tons of hay harvested by soldiers up to Hindenburg Line

Eggs for soldiers

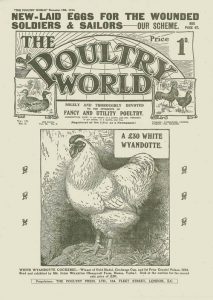

Throughout the war, eggs were not rationed and families were encouraged to keep chickens in their gardens and work on increasing production.

Poultry farming was also used as a method of rehabilitation and a new career for wounded soldiers returning from the Western Front.

Poultry World magazine ran Hospital Egg Week and Eggs For The Wounded scheme to aid the war effort.

Hospital Egg Week was an annual event where eggs were collected nationally and distributed into London hospitals via the magazine’s offices in Fleet Street, with Poultry World meeting the cost.

Columnist Will Hooley wrote that, in the face of war, it was a “national duty” to keep poultry.

The Eggs For The Wounded scheme was launched on 28 August 1914 with the announcement: “Every British hen should be on active service.”

By Christmas 70,000 eggs had been collected through 200 depots.

The following April, 200,000 eggs were being collected each week, and by 1917 one million eggs a week were being distributed from Poultry World readers.

Farming at the Western Front

Many units in Europe created garden allotments and took on poultry-keeping, as well as helping Belgian and French farmers with harvest work behind the front lines.

This work gave the men worthwhile recreational activity and took their minds off the misery of their normal daily existence in the trenches.

The first piggery was built at a military unit based in Étaples, France, in early 1917, to make use of both camp swill and waste from a nearby army fat extraction plant.

Pig units were soon added to every large military base, along with slaughterhouses capable of handling 100 pigs a week.

Goat farms were established near Rouen and Marseilles to provide food for Indian troops – more than one million Indian soldiers served in the First World War.

The Farmer & Stock-Breeder’s Farm Notes: 24 July, 1916

The Farmer and Stock-Breeder was the UK’s leading agricultural journal during the First World War.

It later merged with the NFU’s British Farmer magazine to become British Farmer and Stockbreeder, until it closed for business in 1984.

The following “Farm Notes” appeared in the 24 July, 1916 edition and provide an insight into farming life at the time:

Flintshire – good crops – labour scarce

The hay crops are very good here, but the weather is very bad. There are no men to be got, especially for the milking.

The corn is looking very well, if we could get better weather, and the mangels and turnips are very promising.

A considerable amount of clover and hay has been carried, but there is a lot to get yet. Beef and mutton are making good prices. I saw a beast sold yesterday for £38 and a sow for £15.

Cornwall (Truro district) – better hay weather – corn improved

We are now having a nice time for haymaking, after three weeks of unsettled weather. Seeds are a heavy crop, and old grass has greatly thickened up since the rains.

All corn has greatly improved, and will, I think, make an average crop. It looked slight in most fields a month ago, owing to the cold wind. We all long for the end of this awful war, which is spreading such grief and destruction on every hand.

Surrey and Hants Borders – labour scarce – dry weather wanted

Haymaking is going on very slow on account of the bad weather, but there seems to be a good average crop. Labour is very scarce.

I have been glad to avail myself of the help of soldiers and women. Both have done well. Wheat and oats are looking well, also mangels.

Swedes, too, have come well. Stock are keeping at very high prices. Good cart horses for sale are very few and far between.

What is needed most is a spell of nice dry weather to improve everything. I was sorry to hear of Lord Selborne’s resignation. We hope that these serious times will soon come to a successful end.

The following letter from a soldier on the Western Front also appeared in the 24 June, 1916 issue:

Sir, Each week I eagerly await the arrival of the “F. & S.” which I may say passes through numerous hands, for our battalion contains many sons of the soil.

The article in “F. & S.” on “Ex-service men and the land” to me seems most inspiring, and if only the suggestions are acted upon by some public or government body all expectations, I consider, would be fully realised.

In my opinion, and I am supported by others, the most desirable way to induce ex-service men to go to the land would be by way of establishing training institutions for the inexperienced, courses to cover one year, and to consist of arable farming, dairy farming, mixed farming, poultry farming and market gardening.

This in our estimation, in conjunction with the suggestions of Majority and Minority, would be more attractive and practical than the Small Holdings scheme.

The following editorial comment expresses the editor’s view on the War Savings Campaign:

War savings campaign

Farmers are not less patriotic than any other class of the community. Their riches may be in a less liquid or realisable state than those of the salaried official or business man, but their savings, such as they are, are of peculiar value at the moment when the country requires whole-hearted support.

The War Savings Week, with its campaign from one end of the country to the other, has brought home to the masses the need to supply the sinews of war.

The form of investment which is receiving very wide patronage is on the five years’ basis, individual holdings being limited to £387 10s. A sum of money is deposited which grows until the time of repayment matures.

There is a stern duty thrust upon the brave fellows at the Front, and a responsibility of a different kind on those at home.

We cannot all fight, but we can see to it that the nation’s credit is sufficient for every call.

Sources

- Farming and the First World War, NFU-commissioned report

- Farming and forestry on the Western Front 1915-1919, Murray Maclean

- British agriculture in the First World War, PE Dewey

- Effects of the Great War upon agriculture in the United States and Great Britain, by Benjamin H. Hibbard