Agriculture Bill seeks better deal for farmers in supply chain

© ING Image

© ING Image The new Agriculture Bill, tabled in parliament just over a week ago, commanded a large number of column inches in the national and specialist media, mainly focused on the government’s continuing drive towards a so-called “Green Brexit”.

Most of this coverage was based on the press release and briefing note issued by Defra ahead of the publication of the full 62-page bill – and was pretty useful in terms of setting the scene.

In summary, we learned:

- Direct payments will be paid in full in 2019 and 2020, and will then be phased out during a seven-year transition period

- Cuts to direct payments will be “progressive”, with smaller farmers giving up less than larger beneficiaries

- Money syphoned off in this way (worth £150m in the first year of transition) will be used to pilot a new Environmental Land Management (ELM) system

- Some of this money may also be spent on helping farmers improve their productivity

- Any direct payments post-2020 will be “delinked” from a requirement to farm, enabling farmers to use the money to invest, diversify or retire

- Attempts will be made to simplify the system of applying for support, but farmers will still have to meet “a strong regulatory baseline”

See also: How Michael Gove’s Agriculture Bill will reshape UK farming

The NFU and other lobby groups have been quick to point out that the Agriculture Bill itself is just “enabling” legislation.

It provides the government with the powers it needs to allocate funds to agriculture and to intervene in the way it sees fit. But it does not specifically deliver many of the things Defra has been trailing in terms of cutting payments and replacing them with new “green schemes”.

Despite this, a policy statement issued by Defra on Friday 14 September does add some flesh to the bones, and sets out clearly how the bill will enable it to achieve its ambitions.

The Agriculture Bill

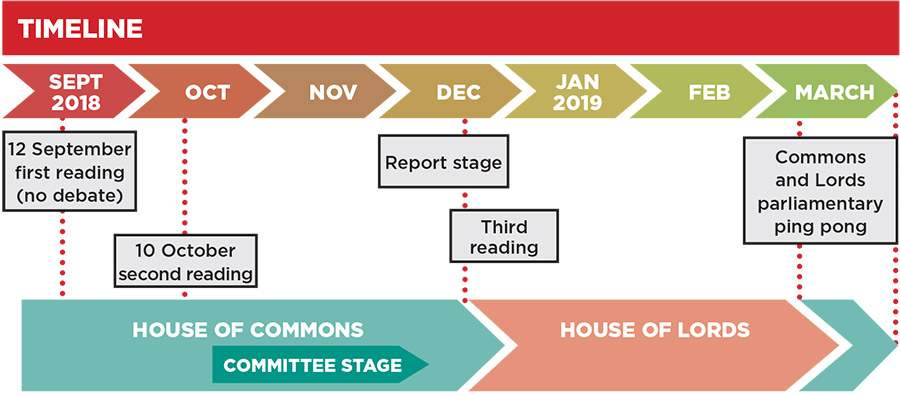

The new Agriculture Bill, tabled in parliament on Wednesday 12 September, is divided into nine separate parts.

Parts 1 and 2 deal with financial support, allowing the government to “spend public money on public goods” – the centrepiece of its long-term policy. It provides for the delivery of environmental outcomes such as clean air, thriving plants and wildlife, and mitigating climate change. It may also pay for enhanced animal health and welfare.

The bill also allows ministers to make payments during the transition period to improve farming productivity. “This could include supporting investment in technologies and methods that can help farmers reduce the use of inputs such as fertilisers and pesticides, while maintaining or increasing production,” it says. Such support could be in the form of grants, loans, loan guarantees or capital allowances.

This part of the bill also provides for the phasing out of direct payments. The statement says these payments will be based on a historic reference period “regardless of whether the recipient continues to farm or not”. “There will be no need for the farmer to have land or payment entitlements,” it adds.

The bill also paves the way for changes to the compliance and enforcement regime. “We will adopt a more streamlined and focused regime, with more data sharing, reduced duplication and greater use of ‘earned recognition’,” it says.

Part 3 deals with the collection and sharing of data, with the aim of improving transparency in the supply chain. “With more transparent data, food producers will be able to respond more effectively to market signals, strengthen their negotiating position at the farm gate and seek a fairer return,” says Defra. “Better data will also enable farmers to benchmark their performance and manage risks to their business.”

Part 4 provides the government with powers to intervene in agricultural markets. It would only apply in times of extreme market disturbance, and could take the form of loans, guarantees or other payments. The aim is to provide reassurance to the sector, while maintaining an agriculture industry “resilient enough to survive in a free market”.

Part 5 relates to marketing standards – for example, the grading of eggs and the classification of carcasses in slaughterhouses in England. The aim is that this should protect farmers and consumers, and take account of other objectives such as animal welfare.

Part 6 deals with producer organisations and fairness in the supply chain. As well as encouraging collaborative working, the government plans to publish, maintain and enforce statutory codes of practice and provide for mandatory contract terms between farmers and suppliers. “These will improve fairness and protect producers from unfair trading practices,” says Defra.

Part 7 provides government with the powers to set financial limits on the level of farming subsidies in all four parts of the UK in order to comply with World Trade Organization rules.

Part 8 grants similar powers to Northern Ireland and Wales to those that will apply in England, though in Wales financial assistance can go wider to support rural businesses and communities more generally.

Part 9 is largely to do with the mechanisms for passing legislation.

The importance of food production

The Agriculture Bill was initially criticised for the lack of attention given to commercial food production, but the Defra policy statement seeks to redress this.

“Our priority is a productive, competitive farming sector,” it says. “British farmers play a crucial role in our food chain, and our future policy will support farmers to provide more home-grown, healthy produce made to high environmental and animal welfare standards.”

The statement insists that food security is built on strong domestic production, but also requires access to safe, high-quality imports from a diverse range of countries. “This will not change after we leave the EU.”

Using the powers in the Agriculture Bill, the government pledges to:

- support innovation to improve productivity

- improve investment in farming equipment, technology and infrastructure

- facilitate collaboration and pioneer the use of more innovative and efficient farming techniques

“A changed regulatory culture, a skilled workforce and investment in R&D can all help the sector to thrive and maximise its trading opportunities,” it says.

Environmental Land Management

The Defra policy statement also sheds more light on how the new ELM system will operate.

“In sharp contrast to the inflexible nature of the current system, these contracts will be based on a land management plan developed by the farmer or land manager,” it says. “Their plan will set out how they intend to deliver the environmental benefits identified, based on guidance and specialist advice.”

The new system will retain a strong focus on results, and will encourage farmers and land managers to review and revise approaches throughout the year to deliver the best results.

A simplified application process will operate throughout the year. Payments could comprise multi-annual payments, capital grants and/or payments for collaboration and local engagement.

The new ELM system will be piloted before it is rolled out nationally. “This will include new and innovative delivery mechanisms, like payment by results and reverse auctions.”

NFU view

By Nick von Westenholz, director for EU exit and international affairs

Nick von Westerholz © David Stock

The landmark publication of the Agriculture Bill has set in train the hugely important process of introducing a new post-CAP domestic agricultural policy; one designed specifically for the needs of UK agriculture.

We know that the current government is keen to frame its replacement of CAP in the context of a broader “green Brexit”. But this is not simply shorthand for paying for environmental work.

The bill also includes powers to provide financial assistance for improving agricultural productivity, to take measures to improve the functioning of the market, and to intervene in the event of severe market volatility.

It is reassuring that these aspects reflect the NFU’s own vision for future agricultural policy: one that supports farmers to undertake important environmental work, to improve the productivity of their businesses, and to manage the volatility and tough market conditions that fall outside their control.

Even so, the bill can certainly be strengthened on many fronts. For example, we still object to the approach to phasing out direct payments that discriminates on the basis of size of claim.

The really key point is this, however; once it becomes law, the work to develop an effective and constructive agricultural policy begins in earnest.

Numerous aspects of future agricultural policy may not form part of the final Act of Parliament that the bill will become – for instance, the detailed approach to phasing out direct payments, budgetary commitments and the balance between delivering public goods and food production. These issues depend on how government chooses to use the powers that the bill provides.

The challenge, then, will not only be to improve the bill to ensure it provides a watertight framework for government support, but also to secure clear and cast-iron commitments from the government about how it intends to use those powers in the years ahead.

It must build a future where farmers, as food producers, can improve their productivity and resilience while caring for the environment, and where our country can continue to benefit from a safe, secure and affordable supply of British food.