Myth buster – the BBC’s anti-meat programme examined

Liz Bonnin © Raw Factual Ltd/Olly Bootle

Liz Bonnin © Raw Factual Ltd/Olly Bootle The recent BBC investigation Meat: A Threat to our Planet? has caused quite a storm.

Even as it was airing, social media was alive with comments. Consumers were aghast at what they were seeing in terms of animal welfare and the environmental damage caused by livestock production in various parts of the world.

Environmentalists were quick to praise the programme for bringing the public’s attention to the issue.

“Far better not to eat meat at all,” tweeted the Guardian’s George Monbiot. “For all that, this film is a big step forward for the BBC, and @lizbonnin was great.”

See also: BBC’s biased views on meat will hit consumer confidence

Meanwhile, British farmers vented their frustration at what they saw as being tarred with the same brush as US and Brazilian cattle producers, while the programme remained almost silent on the high standards to be found on British farms rearing grass-fed beef.

The ripple effects of the programme continued in the days after, with the levy boards writing a strongly worded letter to the BBC, accusing the corporation of biased reporting and demanding UK farmers be given equal opportunity to tell their good-news story.

But wherein lies the truth? Just how sustainable are British livestock farms. Here is our assessment of what was suggested in the BBC documentary and what is the reality in the British livestock industry.

Beef imports

The BBC said: “Brazil is the world’s biggest exporter of beef and it exports thousands of tonnes to the UK every year.”

Fact: According to latest government trade statistics, in the year to September 2019, the UK imported a total of 181,650t of fresh and frozen beef.

The vast majority of this (175,800t) came from other EU countries – with the Republic of Ireland accounting for the lion’s share.

Non-EU countries shipped just 5,850t in the first three-quarters of the year, with Brazil responsible for 1,234t – or less than 1% of the total.

“As a farmer and an economist, context and perspective is everything,” said AHDB market intelligence director Phil Bicknell.

“We produced 925,000t of beef and veal in the UK last year – that context is important if we are trying to understand the true picture.”

Methane production

The BBC said: “There is another big problem with all farmed cattle, including free-range cows – they produce vast amounts of a greenhouse gas that warms our planet. Methane is an extremely potent greenhouse gas – almost 30 times more powerful than carbon dioxide”.

Fact: The significance of methane as a greenhouse gas has been called into question by Miles Allen, professor of geosystem science at Oxford University.

Writing in Farmers Weekly earlier this year, he explained that, unlike carbon dioxide which accumulates in the atmosphere as it is produced, methane dissipates over a relatively short period (10-12 years).

As such, a farmer who maintains his herd at the same size it was a decade ago will be making little difference to global warming, as the methane emitted by the cows today will be offset by methane that has dissipated from the cows that gave it off in the past.

“Indeed, if we were to reduce UK agricultural methane emissions by 20% between now and 2050, that would be enough to fully compensate for the ongoing global warming impact of carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide from agriculture, even if these are reduced to zero over the same time period,” said Prof Allen.

Worse than transport?

The BBC said: “Over the course of a year, the burps from a single extra cow heat the planet as much as burning around 600 litres of petrol. Together with all other livestock, the meat industry now produces more greenhouse gases than the running of all our transport”.

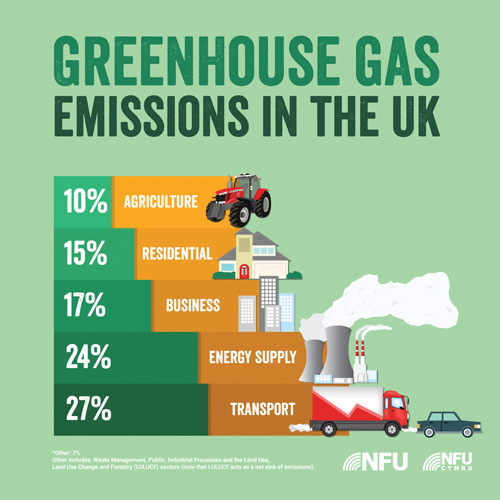

Fact: As far as the UK is concerned, this claim is completely erroneous. Figures from the Committee on Climate Change show that UK agriculture as a whole accounts for 10% of greenhouse gas emissions, compared with 24% for energy supplies and 27% for transport. Furthermore, of farming’s 10% contribution, just 4.5% is from livestock.

Even for global livestock production, the figure is out of date. The 2006 UN Food and Agriculture Organisation’s (FAO) report, Livestock’s Long Shadow, suggested that livestock produced 18% of the world’s greenhouse gases compared with 14% for transport.

But the FAO was not comparing like with like, as it was taking the whole lifecycle of animals – from birth to the plate, including transport – while measuring the emissions from cars at one point in time.

The figures have since been revised, with FAO livestock experts Anne Mottet and Henning Steinfeld confirming that, while direct emissions from transport account for about 14% of all emissions from human activities, “direct emissions from livestock account for 5% of the total”.

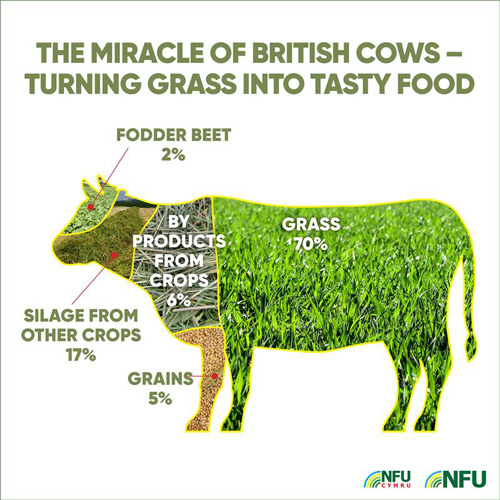

While the overall contribution to global warming is positive, NFU chief climate change adviser Jonathan Scurlock says grass-fed beef still helps maintain a large store of carbon in pastures.

This can be enhanced by improved practices like mob grazing or strip grazing, which result in less poaching and better grass growth.

Soya imports

The BBC said: “An area of Cerrado (in Brazil) bigger than London is used to grow soya that is exported to the UK almost entirely to feed our farmed animals.”

Fact: The Agricultural Industries Confederation (AIC), representing feed manufacturers, says this claim is also out of context.

“The UK imports just 2.75m tonnes of soybeans and soya meal a year, out of a global production of 340m tonnes – so less than 1%,” said AIC head of animal feeds James McCulloch.

“About 20% of that comes from Brazil, mostly as beans for crushing. Under the 2006 Amazon Soy Moratorium, none of it comes from the Amazon biome.”

Furthermore, the UK is fully signed up to the EU’s responsible sourcing protocol, which also ensures imports only come from suppliers who respect workers’ rights, avoid illegal deforestation and maintain good agricultural practice.

Mr McCulloch described the BBC programme as “insufficiently balanced”, as it failed to explain that many of the inputs used by feed manufacturers are by-products of human food production, such as soya meal, rice brans and brewers’ grains.

“We are also using 650,000t of reject food to recycle for animal feed in the UK, which would otherwise go to landfill.”

Fishmeal imports

The BBC said: “Around the world, almost 4m tonnes of fish are turned into fishmeal to feed livestock every year. In the UK it is fed to some of our pigs and chickens.”

Over-fishing of sardines and anchovies for fishmeal production was devastating the South African penguin population, it added.

Fact: The UK does indeed use around 100,000t of fishmeal a year for animal feed – but the vast majority comes from EU suppliers or from Peru, which has responsible sourcing protocols. None is imported from South Africa.

Pollution incidents

The BBC said: “UK meat farming is not as intensive as in America, but it’s still the cause of serious pollution incidents on a weekly basis.”

(This was stated while showing footage of algal blooms and dead fish in a river delta that is clearly not in the UK).

Fact: According to the Environment Agency’s latest report, there were 77 serious pollution incidents in 2018 from agriculture as a whole.

But of these, 25 were related to odour from the pig and poultry sector, while 29 were dairy-related, of which 26 involved slurry.

“In 2018 there was a 28% decrease in the number of incidents caused by dairy farming – dry weather may have contributed to this,” it said.

Meat consumption

The BBC said: “The solution lies with how much (meat) we consume. The latest research says that to meaningfully reduce the impact of meat production, we need to cut down to a few hundred grams per week. Just one of two portions”

Fact: This claim about eating just a couple of portions a week to save the planet was made in the Eat-Lancet report published in January.

Much like the BBC’s latest programme, it drew much criticism for using global emissions data to make recommendations for UK consumers.

The suggestion that we should be eating just 14g a day of red meat and 29g a day of chicken has been challenged by Cambridge University obesity researcher Zoe Harcombe, who said the move to a plant-based diet would leave consumers short of haem iron and vitamin B12.

Red meat also contains numerous minerals needed for a healthy immune system, as well as vitamin D.

“Meeting the nutritional needs of a growing UK population from plant-based proteins alone would likely rely much more heavily on imported foods, which can have a bigger environmental impact,” said AHDB beef and lamb strategy director, Will Jackson.

Organic farming

The BBC said: “Some farmers around the world are rearing livestock in a way that takes better care of the planet, using farming methods that support soil health without the need for chemical fertilisers and pesticides, rearing fewer animals that don’t overgraze, allowing the land to recover.”

Fact: British livestock farmers produce some of the most sustainable red meat in the world, using both organic and conventional grazing systems

According to NFU livestock chairman Richard Findlay, both can offer benefits for the land, enhance biodiversity and increase organic matter within soils to encourage carbon capture.

“Environmental delivery needs to be measured on how efficiently the land and the animals are managed, rather than focusing purely on the farm system,” he said.