Inset v offset carbon credits: benefits and risks to farmers

© Tim Scrivener

© Tim Scrivener When you start thinking about buyers of carbon credits or certificates, most people immediately think about big corporations outside of agriculture looking to balance their emissions through buying someone else’s reductions.

This is known as offsetting. Companies use these offset credits to make claims about how a product, activity, or the whole business is, or is moving towards being, carbon neutral or net zero.

See also: Farm cuts diesel costs and improves yields in move to regen

There is also a market for buying carbon certificates from within a supply chain, a practice called insetting.

The distinction between the two is critical for farmers to understand, industry experts stress.

So what are the differences, and the risks and benefits, between selling carbon offsets and insets from agri-carbon?

What are carbon credits?

Carbon credits or certificates are created by reducing or avoiding emissions that would have otherwise happened, or by taking carbon from the atmosphere and storing it, such as in trees or soils.

Source: Opportunities of agri-carbon markets, Green Alliance

Within a supply chain

The first key difference between an offset and an inset carbon credit is that insets are bought by companies within a supply chain.

There is a further nuance as insets are typically used to balance a particular type of emission – Scope 3 emissions.

Scope 1, 2 and 3 are emissions categories used for accounting purposes.

Scope 1 covers emissions created directly by the company, while Scope 2 and 3 are indirect emissions.

Scope 2 includes purchased emissions, which the company has some control over how much is emitted, such as the use of electricity.

Scope 3 covers all other indirect emissions that are produced within the supply chain, including the direct emissions from a farm producing the raw ingredients for a food product, for example.

These differences matter, particularly if, as a seller of agri-carbon, you have concerns about your farm’s ability to align with net-zero targets in the future, says Andrew Voysey, head of impact and carbon at Soil Capital.

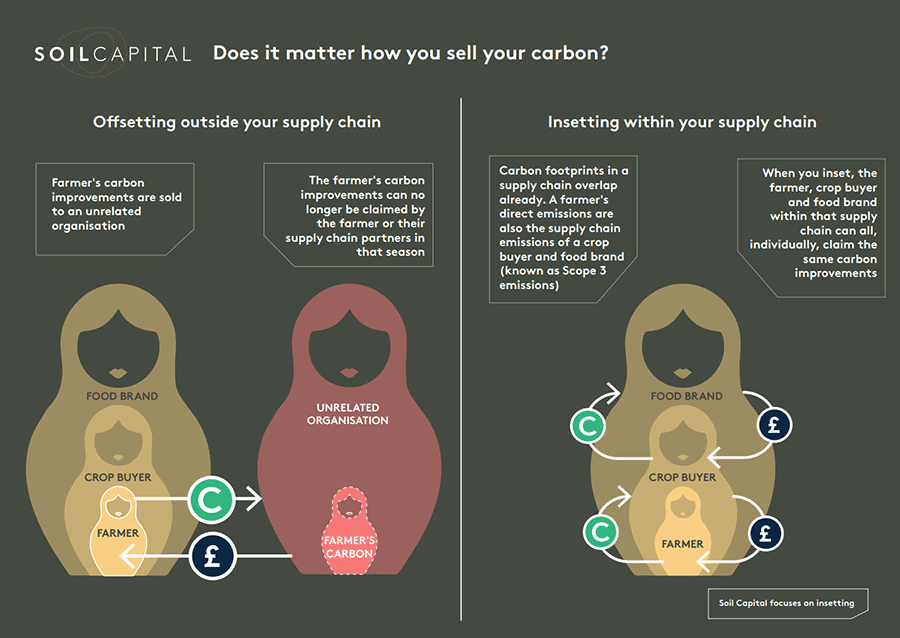

He uses a Russian doll analogy to help explain why it could matter who you sell your carbon to, with the supply chain represented by one set of related dolls and unrelated organisations by another set.

“With offsetting, the farmers’ carbon improvements are sold to an unrelated organisation.

“Those improvements can no longer be claimed by the farmer or the supply chain because the unrelated organisation is relying on those carbon improvements to say something about its carbon footprint – for example, it’s carbon neutral.

“If both were saying the same thing, it would be double counting. That’s well understood.”

Insetting

But insetting is less understood, he says.

With insetting, the carbon stays within the supply chain so each of the partners within it – from farmer to crop buyer to food brand – can claim a reduction in carbon footprint from improvements made on farm.

The farmer’s carbon footprint is included within the crop buyer and food brand’s carbon footprint from buying in raw materials to make their products.

It is part of the crop buyer and food brand’s Scope 3 supply chain emissions and can be taken into account before any carbon improvements are made, he explains.

Each supply chain partner benefits from the carbon improvements made on farm, as it reduces the farmer’s Scope 1 direct emissions and also the crop buyer and food brand’s indirect Scope 3 emissions, because the raw materials now have a lower carbon footprint.

It also opens the possibility of each supply chain partner contributing to the inset payments, potentially increasing their value to the farmer, although this isn’t happening currently.

But the buyer of the carbon must use it to balance its supply chain Scope 3 emissions.

If the credits are used by the buying company to balance their Scope 1 or 2 emissions they can no longer be used by the supply chain or the farmer.

That raises the question about whether the carbon credits are being used against Scope 3 emissions.

Mr Voysey says for Soil Capital, 80% of whose certificates are currently sold as insets – there is transparency through a public registry that enforces their use as Scope 3 insets.

Insetting advantages and risks

- Carbon improvements are sold within supply chain, not externally

- Farmer remains able to claim carbon improvements for his own carbon footprint, unlike with offsets

- Inset credits must be used to reduce buyers’ Scope 3 emissions

- Farmers do not necessarily have to be a customer of the buyer under current rules

- Will supply chain buyers force farmers to make improvements for market access?

- Could insets create a perverse market incentive for farmers not to improve their carbon footprint on farm unless paid for by a supplier?

Does the farm need to be a direct supplier?

There is also a grey area around whether the farm needs to be a direct supplier of the company purchasing inset certificates.

Some schemes, such as Soil Heroes, attempt to set up a direct relationship between a buyer and a customer, while other, such as Soil Capital, use a looser method of determining a link.

“There is a methodology used to determine whether there is a supply chain relationship,” Mr Voysey says.

“Because in most cases we are dealing with commodity supply chains [there is no traceability], carbon accounting verifiers have had to come up with a method to confirm a supply chain link that is good enough, when in practice we don’t know which grain is going to whom when it has been mixed in a silo.”

Soil Capital currently uses the “Supply Shed” definition developed by third party verifier Gold Standard which gives a couple of different ways to establish whether a link exists between a farmer and crop buyer.

“There is, perhaps, a surprising amount of flexibility currently,” he admits. “It can be as simple as the crop buyer purchasing wheat from the region the farm is growing wheat in.

“It is a grey area, but it is practical given the nature of commodity supply chains.”

Perhaps a greater concern for farmers is whether businesses in the supply chain take the carbon improvements without paying for them by forcing farmers to make improvements as a condition of market access, Savills’ head of rural research Emily Norton says.

The recent Arla announcement, for example, could be seen in those terms with 7p/litre of the milk price being associated with environmental actions, which the farmer has to do for the value to be paid back to them, she explains.

“I think there are some fundamental questions around ethics and fairness in supply chains.”

Competition between buyers

Competition between buyers is one possible solution.

“If the farmer can sell to a third party for more money, then the supply chain knows it needs to invest at farm level to achieve those outcomes and doesn’t just come and take environmental value from farming,” Ms Norton argues.

But for true competition, the baseline information the farmer collects and uses to enter a scheme needs to be such that it can be used for other schemes, adds Annie Leeson, chief executive officer of soil carbon measurement firm Agricarbon.

“There are certain pre-conditions for different schemes. Understanding what they are, and whether the choice you have made will allow you to qualify for another scheme is important, but not well understood.

“Certain baselines and also contractual arrangements will allow you to participate in certain market types, and some will not.

“Our customers recognise the need for a robust baseline, which is fair to farmers and more comparable with other market schemes.

“This ensures the integrity of soil carbon claims made within the supply chain, as carbon accounting standards are introduced to clarify ‘grey areas’,” she concludes.