Understanding CVT and powershift transmissions when buying a tractor

Tractor transmissions have come a long way since the days of double-clutching and crunching your way between the three or four gears of a basic, unsynchronised box.

Through the introduction of extra ranges and synchronisation, operators have gained more forward and reverse speed options to suit different jobs or conditions and shifting between gears and directions has become smooth and stress-free.

However, the gearboxes that fit into modern tractor drivetrains take these desirable traits to another level by handling the power more efficiently and being far easier to use, even if you’re not familiar with a particular brand.

For most new tractors over 100hp, the buyer is likely to be faced with the choice between a powershift gearbox or a CVT (Continuously Variable Transmission) and there are pros and cons to each.

How does a powershift work?

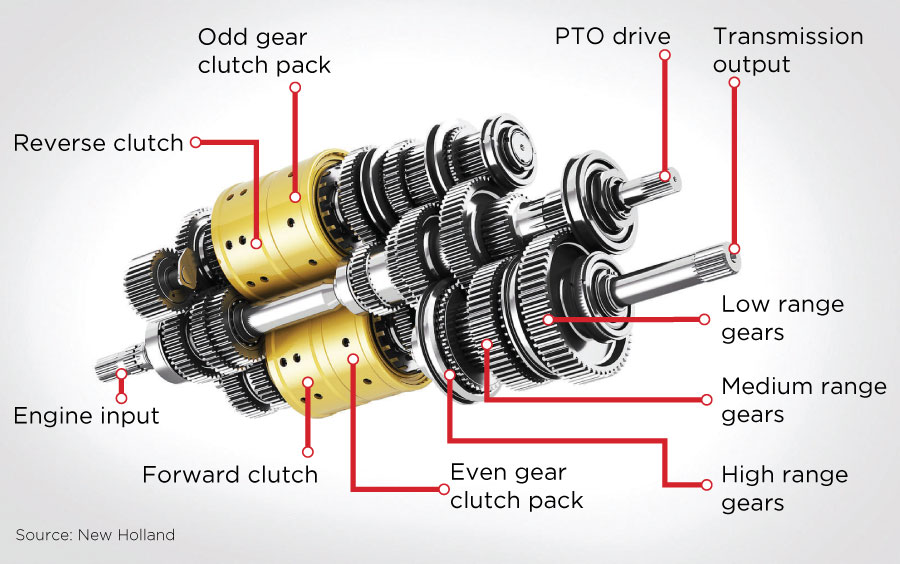

Like any other conventional gearbox, a powershift effectively uses friction plates to transfer the engine’s power to the tractor’s drive axles.

The clever part is the ability to shift through a large number of gears without the need to operate the clutch, which is achieved by using a number of multi-plate wet clutch packs.

Each clutch pack is made up of several discs that are pushed together with a hydraulic piston and released by a spring when hydraulic pressure is freed, or vice versa, depending on the design.

To move between gears, hydraulic pressure is applied via an electronic or mechanical valve to engage the right clutch for the relevant gear situated on a main rotating shaft.

On a semi-powershift, the operator is required to clutch between ranges, but not through each gear within a range, while a full powershift requires no clutching right through ranges and gears. You also don’t need to use the clutch to change direction.

The concept has allowed manufacturers to offer multiple ranges and speeds. A common configuration on the latest tractor models would be four ranges, each with six speeds, offering a total of 24 gears.

On the best setups, the operator can get all the way from 1-24 on the touch of a button and some offer all 24 speeds in reverse.

After setting the engine speed for operation, the operator can then flick up and down the gears as load changes or different speeds are required.

Most modern powershifts also have a fully automatic feature where the appropriate gear is selected by the machine itself based on pre-set parameters, such as forward speed, offering almost the same ease as a CVT.

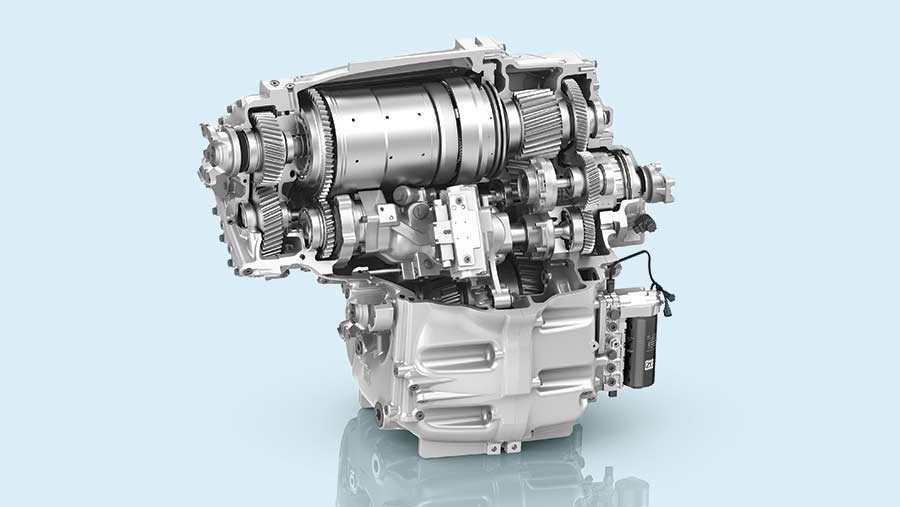

ZF’s CVT gearbox can achieve fuel efficiency gains of over 10% by running at lower revs during work

How does a CVT work?

A car jacked up on one side provides a useful analogy to explain the basic principle of a CVT gearbox.

If you were to put the car in first gear and release the clutch, the differential in the axle would transfer the drive through the path of least resistance, causing the wheel up in the air to spin quickly, while the one on the ground stays completely still.

However, if you apply resistance to the wheel in the air, energy will be transferred to the other side and the car will fall off the jack.

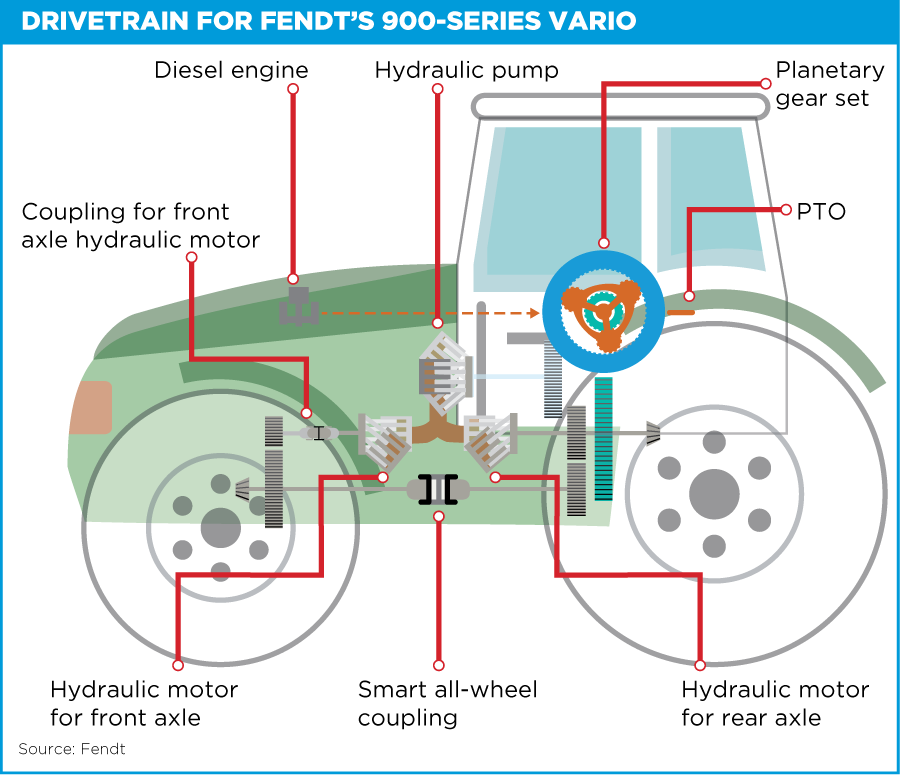

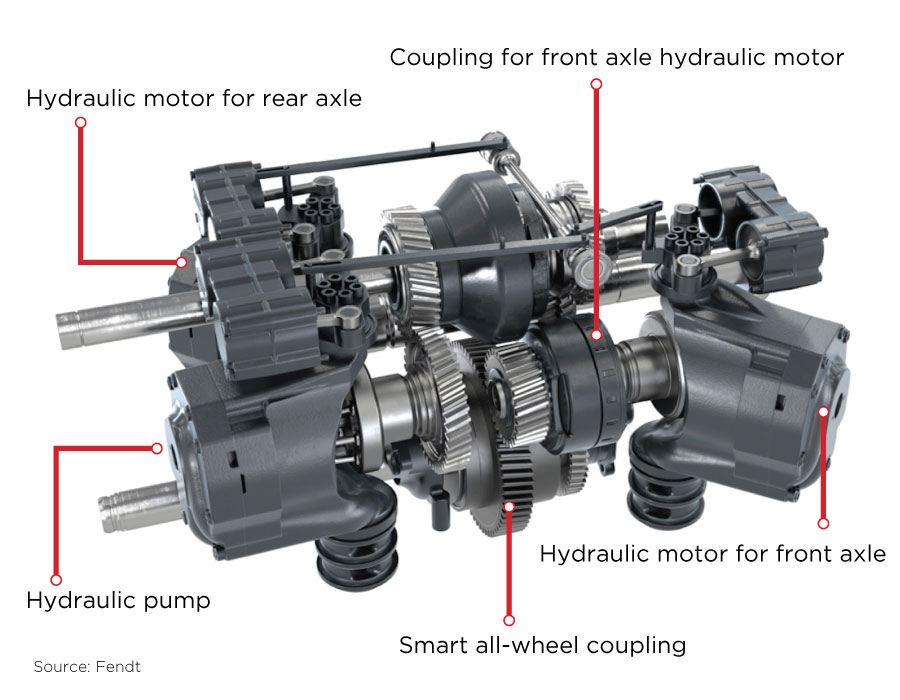

A CVT essentially recreates this process using a combination of hydraulic and mechanical drives linked via a planetary gear system, comprising a sun gear, planet gears and a ring gear around the outside of the two.

The central sun gear is likened to the wheel on the ground, as it is mechanically geared to the engine and rear and front axles, so is initially the path of most resistance.

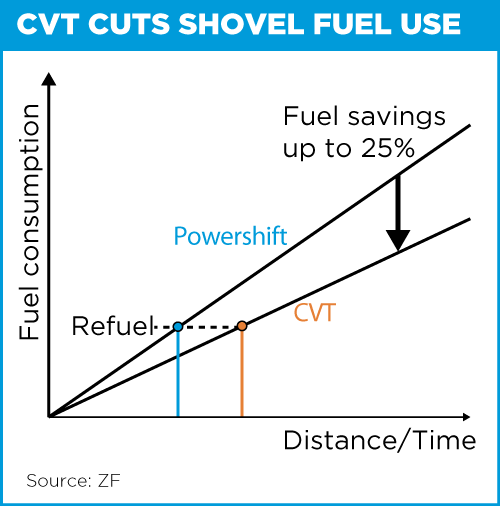

A ZF cPower CVT transmission in a loading shovel has been shown to offer considerable fuel savings over a conventional powershift transmission

The ring gear is likened to the wheel in the air, as it has the least resistance. It drives a hydraulic pump, which in turn feeds a hydraulic motor that is also directly geared to the front and rear axles.

When the engine is turned on, power is transferred through the path of least resistance, turning the hydraulic pump. But when the operator chooses to accelerate, the hydrostatic pump swings out and gradually increases oil flow to the motor, which in turn drives the tractor almost entirely hydraulically.

As the tractor continues to accelerate, the pump steadily reaches its maximum swing angle until its output is at maximum capacity.

The hydraulic motor then reverses the oil flow back towards the pump, decelerating the ring gear and steadily transferring the path of least resistance to the sun gear, so the tractor is driven 100% mechanically as it hits maximum speed.

To go into reverse, the hydrostatic pump is swung in the opposite direction, so the suction side is switched and the tractor is driven in reverse hydraulically. A shuttle clutch aids this transition.

The whole process is completely stepless from a standing start to top road speed, with no need for the operator to clutch or shift between forward and reverse.

Some manufacturers, such as John Deere, New Holland and Case IH, now have CVT transmissions that use electronic clutches to move seamlessly between a number of ranges.

Powershift vs CVT – what are the pros and cons?

So instead of gradually moving from 100% hydraulic to 100% mechanical through the whole speed range or a couple of ranges, such as Fendt’s Vario transmission, they fluctuate between the two across four ranges to improve efficiency.

This efficiency gain is made because the transmission spends less of its time relying on power-hungry hydraulics to drive the machine forward.

| Powershift pros | Powershift cons |

| Lower upfront and maintenance costs | Loss of efficiency through gear changes |

| Easier to maintain on-farm | Shorter lifespan |

| More efficient use of power through mechanical drive | |

| Better for road work |

Take John Deere’s Autopowr CVT box, for example. It operates at a maximum of 40% hydraulic drive, so there is always a minimum of 60% mechanical drive powering the axles.

The sweet spot of 100% mechanical drive in each of its four ranges is at 3.5kph, 11kph, 22.5kph and 47kph on a 6R model and it delivers an overall engine power efficiency of 87% to the drawbar – a figure not achievable with just one or two ranges.

| CVT pros | CVT cons |

| More fuel efficient | Higher initial cost |

| Higher productivity | Requires specialist to maintain/repair |

| More accurate control of speed | |

| Easy to operate | |

| Longer-lasting | |

| Better re-sale value |

Go-to technology

For any operator who has driven a modern tractor over the past 15 years, it is likely that somewhere along that machine’s drivetrain, one of the main components was supplied by German manufacturer ZF from its base in Passau, just east of Munich.

The company’s Gavin Donoghue tells Farmers Weekly that powershifts became the go-to transmission for tractors due to their efficiency gains compared to earlier synchromesh designs, plus durability, relative simplicity and historically, lower cost.

In comparison to a CVT, the lower outlay was due to both the design concept and economies of scale, with powershifts outnumbering CVT units across high horsepower industries, including construction, material handling and agriculture.

This commonality has also meant that there is access to a wide range of parts and services, so maintaining and repairing powershift units is cost effective and can be carried out by able technicians in the field.

“Powershift has been a popular selection but this has gradually changed over the past 10-15 years with the strong emergence of CVT, particularly in mature markets [such as Europe],” says Mr Donoghue.

Increased efficiency

The introduction of torque converters with lock-up clutches – which bypass the hydraulic drive of the torque converter to offer 100% mechanical drive in certain conditions – has reduced the energy lost through a powershift driveline during operation.

Despite these improvements, CVTs are still seen as a much more efficient way of getting tractor power to the ground, as unlike powershifts they do not have to engage and disengage gears with clutch plates to shift up or down.

The latest CVTs offer significant productivity and fuel efficiency gains of up to 25%. For agricultural machines across a range of tasks and conditions, these gains may not be as pronounced, but will comfortably exceed 10%.

This is achieved by the ability to run engines at a lower and more constant rpm and within a very narrow and efficient power range – or “sweet spot” – during operation, with the CVT box taking care of any required increases or decreases in speed.

Fendt’s latest high-horsepower stepless box uses hydraulic motors

Growing market share

It is this boost in productivity, reduction in fuel bills and ease of operation that is seeing CVTs become much more popular in both construction and agriculture, with most major tractor makers offering stepless boxes as an option on tractors from 100hp upwards.

This is backed up by stats from John Deere, which show that CVT technology is now specified in about one-third of its mid-sized 6R-series sales in the UK, and this upward trend looks set to continue.

For higher-tech and higher horsepower tractors, the proportion specced with CVTs is even higher and now tipped in its favour, as the savings over thirstier diesel-glugging machines is likely to be much greater.

“Premium models, particularly in the high horsepower ranges are now exclusively based around a CVT and even some of the entry and mid-range models are starting to integrate CVT,” explains Mr Donoghue.

He adds that it is only the cost sensitive tractor markets where powershifts still dominate, or for smaller, basic tractor models used for simple tasks in developed regions.

John Deere’s tractor specialist Christian Nightingale agrees, and says that when looking at the 80-130hp options the firm offers, the vast majority are sold with its PowerQuad or AutoQuad mechanical powershift.

However, when moving to about 130hp, its Autopowr CVT box is gaining in popularity and he says once a buyer has invested in the slightly more expensive transmission, they will almost inevitably opt for the same again when replacing the tractor.

Mr Nightingale explains that from a practical perspective, the main draw of the CVT is the much-improved driveability for operators, but there are also some other factors that drive uptake.

“Slow speed work is where CVT comes into its own, as we can take our tractors down to just 50m/hr. For pto operations in potato and veg seed-bed preparation, you can’t always get down to that speed with a mechanical gearbox without fitting a creeper box.”

There are also practical reasons to opt for a powershift, he adds. “Where you are mostly doing haulage with minimal fieldwork, we’d always advise customers to go for a mechanical transmission, as it offers better power efficiency on the road.”

New Holland’s double-clutch powershift is available on all T6s and the Case Maxxum

Operational lifespan

CVT boxes tend to have a longer operational lifespan than powershifts, as the clutchplates used to shift through the gears and ranges in a powershift are subject to wear.

Comparing the two in agriculture is difficult, as a tractor can be put to various uses that cause different levels of stress on the drivetrain, so construction provides a suitable example.

On a large loading shovel doing about 1,500 hours per year on a single task, ZF has seen its CVT transmissions have an extended lifespan over a powershift in the same situation and have been known to last up to 30,000 hours. Two engine rebuilds were carried out during that time.

However, tractor manufacturers now offer, or have easy access to, off-the-shelf re-manufactured CVT units at ever decreasing cost due to the rising popularity of the technology.

This makes prolonging a machine’s life – like many powershift users have done in the past – no longer out the question, because when a CVT fails a dealer can replace it quickly and easily and even throw in extra warranty.

The one drawback is that any work carried out on a CVT typically requires a specialist due to its hydraulic pump and motor components.

What about cost?

Although the initial outlay can be more for a CVT, fuel savings and potentially lower maintenance costs may make “total cost of ownership” on a long-term investment more favourable than a powershift transmission.

However, if a buyer is only keeping the tractor for a short period, they would need to question whether they would accrue enough savings to justify the extra cost of a CVT on its spec sheet.