Tips for buying a second-hand Challenger MT765E tractor

Challenger MT765B © Adam Clarke

Challenger MT765B © Adam Clarke Rising input costs, falling subsidy payments and squeezed profit margins mean many farmers are turning to the second-hand machinery market to add extra firepower or replace their ageing prime mover.

And, while there has been a notable shift to more versatile wheeled tractors, demand remains surprisingly strong for used twin-track Challengers that, if picked carefully, can provide abundant horsepower at a fraction of the cost of buying new – even when extensive rebuilds are factored in.

However, they’re not cheap, so anyone planning to pull the trigger on a £100,000-plus purchase should do their homework first.

Graham Foster-Coy of Challenger specialist GFC Engineering guides us through some of the most important things to look out for.

See also: John Deere tractors: Common problems and how to fix them

What can you pick up second-hand?

You can pick up MT700 series (2002-4) and even MT700B series (2005-8) machines for less than £40,000.

We are seeing a lot of these end up at smaller arable units where the farm isn’t the primary income source.

They get a big machine with more horsepower than they need so that they can get a lot done in a short time.

When Challenger launched the MT700E series in 2014 it switched from an Agco Power 8.4-litre, six-cylinder engine to a 9.8-litre seven-cylinder to pass emissions standards.

The compression ratio was higher, so the fuel burned hotter, and the pistons just weren’t man enough to handle it – and that led to a lot of problems.

Agco replaced any engine, no matter how many hours, but it did give the product a kick and those models earned a bad reputation.

As the issue was rectified, you can now get a lot of tractor for your money if buying one of those machines second-hand. They are reliable.

Any big issues to look out for?

The final drives are a weak point on the first MT700s, MT700Bs and MT700Cs. If they’ve been used with heavy linkage-mounted implements, the final drive bearings can break up and cause problems.

Essentially, they slimmed down the rear end to suit the European market, allowing wheel track widths to be set narrower.

This meant the two large bearings that sit on each side of the final drive were too close together, so they were under too much strain and prone to failure.

This was rectified on later models, as the final drives were wider to allow for more space between the bearings.

If you are trying to lug seven or eight furrows mounted, I’d recommend looking at a later model with a wider final drive.

Wide final drive is better © Adam Clarke

Narrow final drive is bad © Adam Clarke

Spending £100,000 on a Challenger MT765E

What are the pros and cons?

This 2014 machine has a 400hp engine and is quite quiet and relatively economical to run.

The service interval is 400 hours on this model, rather than 250 hours previously, which keeps running costs down.

Weights can be quickly changed © Adam Clarke

The good thing about these Challengers is that you can take weight on and off easily, so you could start with a 12.5t machine and load it up in a couple of hours.

You aren’t stuck with a big heavy machine all the time if you are doing a range of operations.

Engine

© Adam Clarke

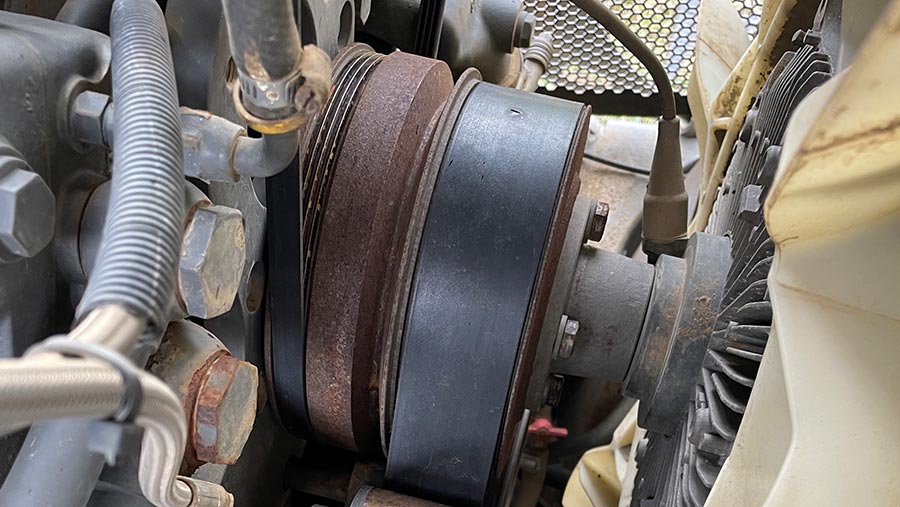

The MT765E has an Agco Power, 9.8-litre, seven-cylinder power unit generating 400hp. You must keep an eye on bearings and belts at the front of the engine, especially the fan belt.

During servicing, you should always uncouple the belts and give everything a spin. If a fan bearing fails, it can come apart and go straight through the radiator, leading to a costlier repair.

Check fan belt bearings © Adam Clarke

That is very rare, and we replace the bearings as a matter of course on a 1,200-hour service, as they aren’t expensive. It is only an hour’s work and £100s worth of bearings.

Always keep the radiators blown out. The transmission cooler is particularly important – it is at the bottom and tricky to get to, but if it’s not kept clean you can end up running the transmission too hot.

Keep transmission cooler blown out © Adam Clarke

Using the wrong oil in the E-series’ Agco engine results in high oil consumption, so check to see if it’s been serviced using genuine oil.

It needs to be a high-grade low SAPS oil (oil that has low sulphated ash, phosphorus, and sulphur). The days of having one drum for all your machines is over.

More for running rather than buying, but you’ve got to use good diesel such as EN590 (which has very low water content) or even GTL (gas to liquid). It’s important because you will be using a lot of fuel – 600-700-litres over a long day.

The filters can do their job in protecting the injectors and the engine, but you will save a lot of heartache by using decent fuel in the first place.

Operators should always keep a set of fuel filters on the tractor but, at £80 a set, you don’t want to be changing them daily.

Transmission

It has a Caterpillar 16×4 full powershift gearbox. You can have a creep option for very slow operations like veg bed preparation, but this machine hasn’t got one.

The transmission is over-engineered for the size of tractor, as it comes from Cat’s experience with big plant.

They plod on forever if looked after properly and there are 20,000-hour tractors out there with transmissions that have never been apart.

Changing the oil every 1,000 hours is vital and it must be recalibrated using the Cat service tool software every time it’s renewed.

The new transmission oil affects the gear change – it becomes very sharp, but resetting helps smooth it back out.

One thing to consider is use of the inching pedal. Operators must understand that the inching pedal is exactly that – an inching pedal for hitching up to implements and other similarly delicate operations. It is not a clutch.

When starting and stopping under load, just put it into gear and let the transmission’s control system do its work. If you use the pedal, you can get the clutches hot and cause unnecessary wear.

I don’t see major problems on the MT700s, but the bigger MT800s can have issues. I usually deal with about one MT800 transmission failure per year.

They are pulling a much bigger load, which makes it a little more likely, but a lot depends on how well a machine is operated.

I tend to do all the heavy work and strip them out. They are then sent to a transmission specialist up north that has all the gear to bench test them. That way you get a guaranteed repair.

I can usually spot a transmission problem during a service – either a bit of metal showing up in the oil filter or it won’t calibrate, which indicates that something is worn.

For a rebuild on an 800-series, you’d be looking at £20,000.

Hydraulics

The D-series machines onwards moved from simpler Bosch hydraulics to Husco with electronic Canbus controls on the linkage and spool valves.

As they are a bit more complicated and rely on more electrics, they can have niggly problems.

If a machine is throwing up hydraulic error codes, it should be investigated straight away.

The system is modular, so fixing the issues often costs a few hundred quid for a switch or Canbus module.

The hydraulic pump fails occasionally, which is often due to a lack of servicing.

If you don’t keep it clean, there are large volumes of dirty oil going around the system and it is going to wear components out.

Look out for machines that have been on and off a wide range of implements, as this can suck up lots of contaminated oil and quickly lead to problems.

All the wiring and cables around the electronic hydraulics and transmission are a haven for mice, so make sure that is all clean before storage.

Running gear

Idler bearings © Adam Clarke

Changing the rear drive reaction arm oil on every service is the best thing you can do to keep things running smoothly.

It’s an arm that is connected to a central freewheeling hub that only holds a litre of fully synthetic 50-grade oil.

There are two big bearings in there and they can fail in a bad way. It’s a £5k job to replace each one.

The oil does break down over time, so if you change it every 400 hours then you should never see an issue.

However, I do get a few calls from new Challenger owners reporting oil on the inside of the track and they aren’t aware there’s oil in there.

Depending how much road work the machine is doing, it pays to check and change the oil in the track idlers regularly.

On the later models, there is a small sight glass which makes life easier, otherwise it’s a drain plug.

The oil is held in by a metal-to-metal seal that is very good at stopping grit coming in. But, if there’s anything breaking up inside, it quickly damages the seal and will start to leak.

Any leak should be investigated and, as the hubs only hold 250ml of oil, even a weep will soon empty it out.

You just run them backwards on to a block so the track sags enough to let you spin the idlers and check for any trouble.

For the larger front idler, you can get issues if you don’t change the oil, especially when doing a lot driving on the road. It should be changed every year as you are soon into four figures for a repair of shafts and bearings.

Tracks

Damage to rubber on drive wheel © Adam Clarke

It’s a good idea to have a look at the guide blocks in the middle of the tracks. Unlike Quadtracs, which are continuous drive, Challengers are friction drive.

It’s essential to keep stones or other debris from getting between wheels and tracks, because every time it goes around it has the potential to dig more rubber out of the drive wheel.

When the operator gets out of the cab, they should give things a visual check and remove any objects with a screwdriver.

It’s worth doing this if purchasing second-hand, and also ensure the tracks aren’t running out of line. If the rubber on the drive wheel goes, it costs about £3,000 for a replacement.

Machines working on very flinty soil types can suffer heavy track wear and need replacing every 2,000 hours.

Typically, on most soil types you’d get about 4,000 hours out of a set. It’s about £15,000 to replace them.

Linkage

Look out for undue wear on the bushes at the top of the three-point linkage lift arms. They are relatively cheap to do, but need replacing often if doing a lot of work with mounted implements.

A regular bush change is much cheaper than replacing heavy metal.

Look out for linkage bushes © Adam Clarke

The link arms themselves are prone to cracking, so are worth a check too.

Cracked link arms are an issue © Adam Clarke

What do the auctioneers say?

According to Cheffins machinery expert Oliver Godfrey, post-2001 Challengers offer affordable horsepower and that has maintained strong demand both at home and abroad.

The machinery auctioneer sells between four and eight each year, and a recent example of a low-houred 2008 MT745B in very good condition sold at a farm sale for £63,000.

One thing turning potential buyers off is the fact that twin-track models have got a reputation for screwing up headlands when compared with a Quadtrac, but sales show they still have a loyal following.

The lighter MT700 series is more popular than MT800 series and there is also keen demand abroad. Machines in good order are going to Germany, regardless of age, with some appetite also in Spain, Portugal and eastern Europe before recent political troubles.

Engines are a talking point at sales and, where a machine might have had an early and troublesome seven-cylinder Agco Power engine, buyers are keen to know if it has been replaced. Confidence soon returns if it has.

GFC Engineering, Challenger specialist

Graham Foster-Coy © Adam Clarke

If you ask most young farmers what they’d like to do, typically the answer would involve spending the day on the biggest kit with the most grunt.

It turns out these same big machines also gets the juices flowing for fledgling agricultural engineers like Graham Foster-Coy.

Starting out just before the Challenger brand was sold by Caterpillar to Agco in 2002, he now has his own specialist business keeping the tracks turning on yellow machines up and down the country.

Here, we look at his journey from apprentice to master.

When did you start working on Challengers?

I started out as a fitter at Oliver Landpower in Luton in 2001, where I did an apprenticeship.

At the time, it was a franchisee for JCB, Claas and Challenger. The relationship with Challenger came about when they started dressing them up in Claas colours in 1997.

As Oliver serviced a lot of heavy land arable farms in the area, they were popular and about 90% of my work was on Challenger machines.

I worked there for about 15 years, until Oliver lost the Challenger franchise, which went to Chandlers at Shefford. They came in with a good offer, so I moved there.

After a couple of years, it felt like it was the right time to take a risk and move on, so I bought a van and all the Cat and Agco electronic service tools.

Oliver Landpower also had a lot of parts left in stock, which I acquired at a good price to get started on my own.

GFC Engineering was born, and the phone soon started to ring. It’s been all go since.

What inspired you to specialise in Challengers?

It is heavy work, and you rarely get an easy day, but once you love them, you love them.

I’ve got some fantastic customers and I’m dealing with their prime mover – it’s a centrepiece like a combine or a sprayer and that brings pressure to keep it going at busy times.

When I started working on them, the Challenger brand was very much a Rolls Royce product, so there was a great intimacy between manufacturer, dealer and customer.

Everyone was on first name terms, and you felt part of a big team.

Even back in 2002 when they moved away from the flat track design and the MT700-series was launched, the tractors were autosteer ready, had Isobus, and its category 3 cab was comfortable and sealed.

For a young fitter, it was exciting stuff and ticked all the boxes.

What areas do you cover?

© GFC

Hertfordshire, Bedfordshire and Buckinghamshire are a given, but I’ll travel all over the country. I look after a hire fleet of Challengers, which sends machines all the way down to the south coast.

I offer the same service as the dealers, with genuine parts and the right diagnostics tools, but because I haven’t got big depots, staff payrolls and other overheads I can do it for a more competitive price.

I look after no end of other machines, like diggers and JCBs, too. Once you get in with a farm, they use you for all sorts of other things.

Before you know it, you’re servicing a Challenger one minute and recharging the air-con in the daughter’s Polo the next.

What is the market like for Challengers?

A lot of businesses have amalgamated, or land is now farmed by large contract operations, so tractors are spending a lot more time on the road.

Although Challengers aren’t all bad on tarmac, those businesses have perhaps compromised a crawler’s performance in the field for the comfort of a Fendt 939 on the road.

That said, tyre technology has come a long way, so the gap has probably closed in the field now.

The second-hand market is still strong and despite any shifts to wheeled tractors or smaller machines, there doesn’t seem to be a drop in service requirements.

With farm incomes getting squeezed and subsidy payments changing, not everyone wants to be lumbered with big repayments on new kit, which is getting more expensive.

Also, with a prime mover, what can a new machine do that an older one can’t?

I am seeing more customers carrying out rebuilds when a Challenger gets to about 10,000 hours.

How much does a rebuild cost?

I’ve currently got a 600hp machine that’s on about 11,000 hours. It’s probably worth £45,000-£50,000 on a good day, it has never put a foot wrong, and the farm loves it.

You can overhaul the engine for about £25,000 and that sort of money won’t get you anywhere near the £400,000-£500,000 for a new Fendt twin-track.

Did the Fendt introduction affect business?

All the Fendt machines are still under warranty for now, so I am working solely on the yellow ones.

I did some product training for the new models when they first came out and will keep up to date, so that I’m ready to go.

It certainly got tongues wagging – it’s a premium product and a dream to drive. I’d say if you’ve got the right operator that gets the most out of it, you’ve probably got the best high-horsepower machine on the market.

Do you get involved in sales?

It takes up a lot of time, and you can sit on a machine for a couple of months with money tied up, which doesn’t appeal.

I will happily answer calls from people looking to buy and wanting advice, though.

I offer appraisals with an honest opinion, and you are better off paying for a few hours labour if it makes sure you are buying a decent machine.

No one can give a categoric guarantee that the machine won’t break down, but you can have a good look around and give them a heads up on any potential issues.

I do that for Rogator sprayers as well.

Once you start chucking £100,000 about, you want to know if it’s in reasonable condition as repair bills can be monstrous if you get it wrong.

The one positive is that you rarely see one that’s been too battered and abused.

A Challenger won’t be a machine that everyone jumps on, so even if it’s done 10,000 hours it may only have had two or three operators.