Driverless tractor helps ease fresh produce labour shortage

© MAG/Edward Mowbray

© MAG/Edward Mowbray Demand for purple sprouting broccoli might be at an all-time high, but the labour-intensive work involved in getting it from the field to supermarket shelves has left growers seriously vulnerable to Brexit-induced staff shortages.

That prompted 23-year-old Tom Beach, whose family grow 25ha of the crop at their 100ha Mudwalls Farm near Alcester, Warwickshire, and farm manager Russell Duggan to come up with a means of automating elements of the picking process.

Farm manager Russell Duggan (left) and Tom Beach © MAG/Edward Mowbray

“Finding people with arms and legs is hard but finding people willing to use them is even harder,” says Mr Duggan.

“We have to rely on agency staff as the workload varies depending on when the crop is ready to cut. We might pass through each field once a week late in the season [March and April] and have a huge harvest, while in December there can be almost nothing to pick.

“That makes it hard to predict staffing requirements – some weeks we need 35 people, but the following week we could struggle to find work for five. And we then have the challenge of getting temporary staff trained quickly enough to pick the right spec crop.”

See also: Engineer adapts Kubota tractors for driverless contracting

Change of system

It’s not currently possible to replace humans with robots, as camera-based systems aren’t yet commercially available and the picking process requires a keen and experienced eye in order to select only the ripe buds. This encourages the plant to keep producing right through the six-month harvest season from September to March.

Instead, Messrs Beach and Duggan decided to focus on maximising the performance of their existing harvesting team.

So rather than having them trudge up and down the fields doing battle with the elements in mid-winter, which would hinder the output of even the hardiest soul, the workforce is now housed in a weatherproof canopy that stretches for 6m to one side of the packing trailer.

Inside the trailer – conveyor belt and packing station © MAG/Edward Mowbray

Inside, the five-strong picking gang walks behind a full-width, metre-high conveyor that carries the crop to the main trailer bed, where it is weighed, crated and stacked by a sixth member of staff.

“One of the main reasons for developing the harvest rig was to have everyone covered so that the weather doesn’t affect our ability to get on the fields,” says Mr Beach. “If we can harvest when our competitors can’t, then we’ll get the premium.”

The trailer is towed along 12m tramlines by what is arguably Mr Beach’s more impressive invention – a John Deere tractor that can be controlled remotely by the person at the packing station.

As well as eliminating the need to have an extra body in the seat to pilot a tractor crawling along at just 0.3kph, it allows the picking and grading team to stop, start, slow down or speed up to suit their immediate workload.

Driverless tractor

The change of system involved two elements – building a picking trailer (see the Building a picking trailer box) and developing a remote-control system for the tractor.

First to get the driverless treatment was a small New Holland orchard tractor with a hydrostatic transmission, electric clutch and fly-by-wire throttle. These components were relatively easy to tap into, says Mr Beach, with a series of cables running from the control module in the trailer to a big fuse box in the cab.

However, once the farm had upgraded to a bigger, heavier, picking trailer, the New Holland was found to be too lightweight, so the farm’s John Deere 6210 was roped in as a replacement.

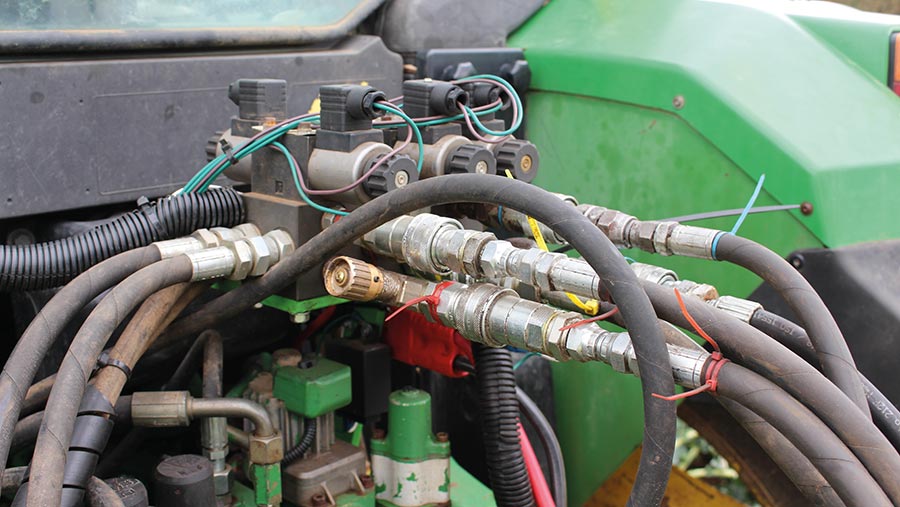

Cetop valve block © MAG/Edward Mowbray

Central to its conversion was a Cetop valve block, mounted above the top link on the back of the tractor. It is plumbed into one of the rear spools and provides the oil supply for four different hydraulic circuits – the steering, brakes, crop conveyor and canopy-fold mechanism.

So, with the spool lever set to constant pumping and the valve block receiving a continuous flow of oil, any one of those functions can be activated by a solenoid linked to the remote control box. This saved having to tamper with the cable-operated levers in the cab, so the tractor can still be used conventionally at any time.

Steering and brakes

It also meant Mr Beach could bypass the standard power-steering system, which was previously activated by the conventional means of turning the wheel.

Instead, the double-acting steering ram is operated using an oil supply from one of the outlets on the Cetop valve block, with the pipe routed down the side of the chassis to the front axle. This allows it to be controlled electrically from the trailer.

For safety reasons, the same ports on the valve block are also used to control the canopy in/out. This means the operator must manually switch the pipes, so there’s no risk of engaging the folding mechanism by accident – at least all the time the power steering is plumbed in.

Tapping into the tractor’s braking system would have been a more complicated affair, so instead Mr Beach reversed the actuation system on the trailer’s hydraulically activated drums.

This means it works on a pressure-to-release (rather than pressure-to-apply) basis, with two heavy-duty springs keeping the brakes engaged all the time the tractor is stationary. As a result, there’s no risk of it rolling while the transmission is in neutral.

Setting the tractor to move forward automatically sends a signal to the brake line, which releases the ram and, therefore, frees the shoes from the drum.

There’s a three-second delay and audible warning prior to this happening, and several emergency stop buttons are dotted around the working stations to allow any member of the team to bring the rig to an immediate halt.

Controlling the transmission

The trickiest element in the switch from the New Holland, with its seamless hydrostatic transmission, to the John Deere 6210 was working out how to control the four-speed semi-powershift Powrquad gearbox.

“Our original idea was for the tractor to trundle along without stopping, allowing the harvesting team to stand right behind the conveyor and nip each plant as it arrived under the canopy. But without a range of creeper speeds, the John Deere couldn’t go slow enough for that to happen, which meant we needed to be able to stop and start it.”

That meant moving two levers on the right-hand console – one for the forward/reverse shuttle and another for the four powershift steps.

To do this, he built relatively crude brackets that are pinned to each lever and attached to a frame bolted to the cab floor. These are connected to electric actuators that are controlled by a series of solenoids.

So, when the “driver” selects forward or neutral, or initiates a powershift change using buttons on the box in the trailer, the actuators physically shunt the sticks into the desired position. And to make sure they extend or retract precisely, avoiding the risk of selecting the wrong speed, he fitted limit switch sensors. However, there’s no means of initiating range changes remotely – these must be done in the cab.

For safety reasons, it’s not possible to engage reverse on the shuttle, either. To do this, an override switch must be flicked in the cab that allows for manual control.

Wiring box © MAG/Edward Mowbray

All this required a maze of electrical wires, each of which was given a numbered tag that relates to its particular circuit, which meet in a big box to the left of the driver’s seat.

Although it would have been possible to programme a computer to transfer the information, Mr Beach says he prefers the simplicity of wires, which make it as unfussy and fixable as possible.

“Having everything on a computer only adds to the complication and we didn’t want to have to use a laptop to solve every issue. Instead, I can call Russ and we can usually trace the fault with relative ease using a multimeter.”

Building a picking trailer

Crop picking at Mudwalls farm traditionally saw an army of workers plod up and down the fields filling boxes to be loaded on a packing trailer but, with no protection from the elements, output tended to drop significantly in bad weather.

To solve this problem, Mr Beach decided to repurpose the trailer by fitting a 6m-wide canopy that would protect the gang from the wind and rain while travelling up and down the 12m tramlines.

His first version cost roughly £2,000 to assemble and included a makeshift £150 tarpaulin roof that was supported by irrigation pipes. The conveyor was sourced from eBay for around £200 and it ran on a recycled chassis and axle from a McHale mixer wagon.

Though somewhat crude, it didn’t miss a day of harvesting through the winter of 2019, and it allowed the person tasked with grading the produce to keep a closer eye on quality.

It also proved the concept worked, so justified the development of something a bit smarter.

This used the same chassis but, to get the weight lower to the ground, the axle was mounted above it, rather than being slung underneath. Though this has reduced ground clearance, it has also eliminated the need for a counterweight to maintain balance with the roof unfurled and jutting out 6m across the crop.

The aluminium cantilever frame, which Mr Beach TIG welded himself, has a central pivot point that is locked in position when unfolded. Production of the canvas canopy was one of only two elements to be commissioned to a third party – the other being the PVC belt for the stainless-steel conveyor, the speed of which can be varied on a small hydraulic valve.

For road transport, it can be folded hydraulically to keep travel width within 3m. However, to avoid the risk of accidentally initiating the folding sequence with people inside the canopy, the hydraulic pipes must first be plumbed into the Cetop valve block in place of the power steering supply.

The left and right buttons on the control box then govern the folding mechanism, with the canopy concertinaed in and the conveyor swung along the full length of the trailer.

“If I were to build the trailer again, the only thing I’d do differently would be to use thinner materials in the construction of the roof. That would make it quicker to fold and keep the weight down. Other than that, it works perfectly.”

As for cost, Mr Beach estimates the total for the tractor and trailer came to roughly £10,000, with the biggest expenses being the £2,500 custom-made canopy and £700 for the conveyor.

FW Inventions 2022

If you’ve built or modified a machine to make life easier, save money or reduce labour pressures then why not enter our Farm Inventions Competition? There are cash prizes totalling £2,550 on offer – all you need to do is send a few details and a high-res picture to oliver.mark@markallengroup.com