Cleanacres Atlas sprayer revived with home-made autosteer system

Cleanacres Atlas sprayer © James Andrews

Cleanacres Atlas sprayer © James Andrews Keen to modernise spraying operations, but happy with the performance of their 1998 Cleanacres Atlas, David and Michael Edwards decided to treat it to some upgrades.

Top of their wish list were autosteer and automatic section control.

Both are key for streamlining the application of seaweed fertilisers and conventional products across some 2,000ha of ground near their farm on the Shropshire/Herefordshire border.

See also: UK made kit converts any tractor to RTK autosteer for £3k

However, with prices for off-the-shelf systems running well into five figures, a low-cost DIY alternative was a far more appealing prospect.

Most of the technical work for this was entrusted to David’s son and Michael’s brother Steve Edwards who works as a service manager for CNH covering the Middle East and Africa.

Left to right: David, Michael and Steve Edwards © James Andrews

Recycled equipment

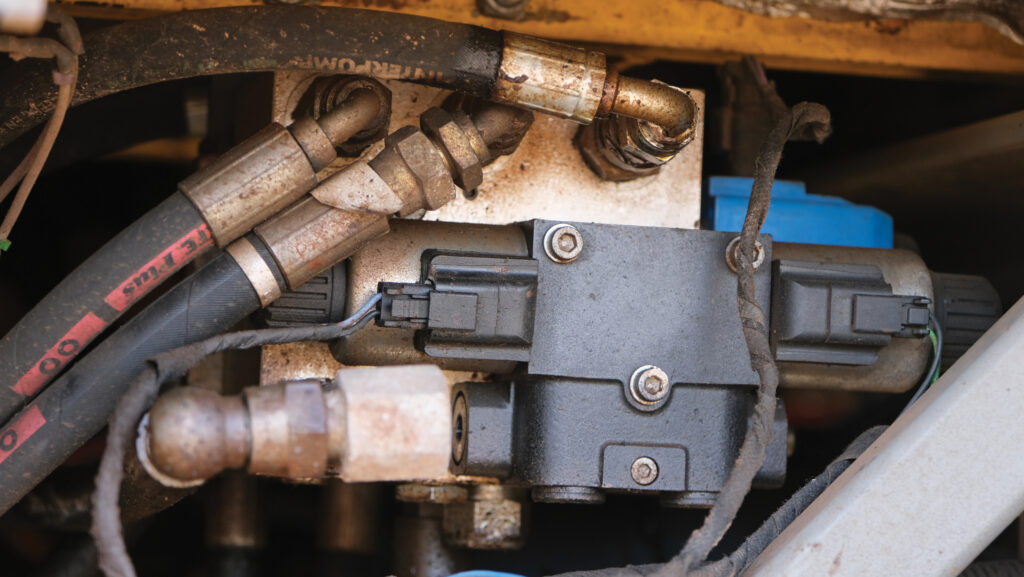

The autosteer valve © James Andrews

First on their agenda was scouring the internet for a hoard of second-hand GPS gear, most of which was Trimble-based equipment once fitted on New Holland and Case IH machines.

The most visible part, the screen, was an isobus compatible Case IH Pro 700 – or Intelliview 4 in New Holland vernacular – which was installed with standard tractor software.

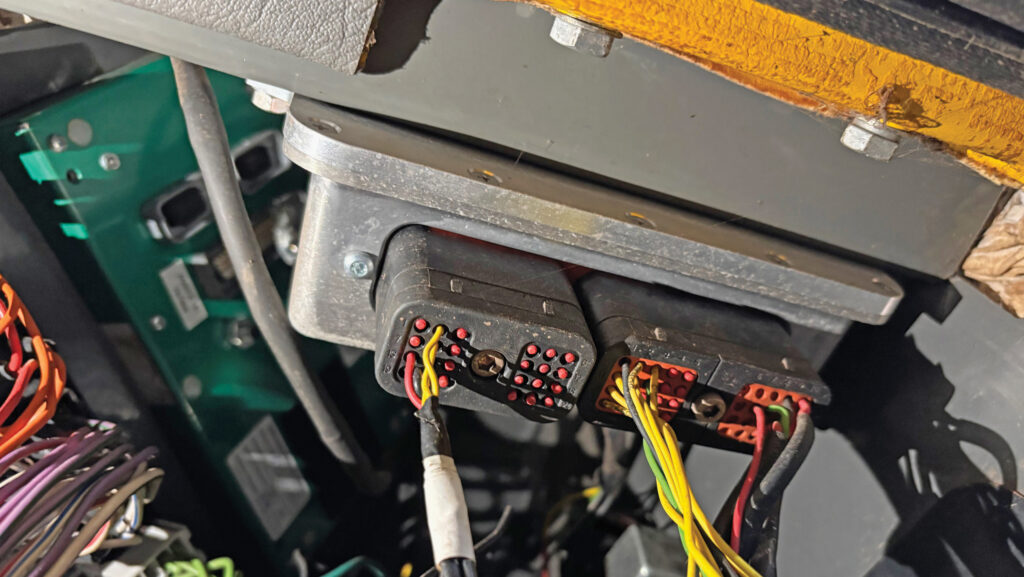

A 372 GPS receiver was also hunted down, as well as a Nav 2 controller which, although hidden from view, is the main brain behind the setup.

Simply plugging all these components together would have given them a rudimentary guidance system, but a bigger challenge was getting it to steer the sprayer automatically.

Nav 2 controller © James Andrews

To do this, a second-hand autosteer valve was sourced from a Puma tractor and painstakingly plumbed into the sprayer’s steering circuit.

The process involved making new mounting plates for the original orbital unit and fashioning the pipework so that the steering would function normally when autosteer wasn’t in use.

For added safety they ensured the pressure switch was working correctly so that the system would disengage instantly as soon as the steering wheel was grabbed.

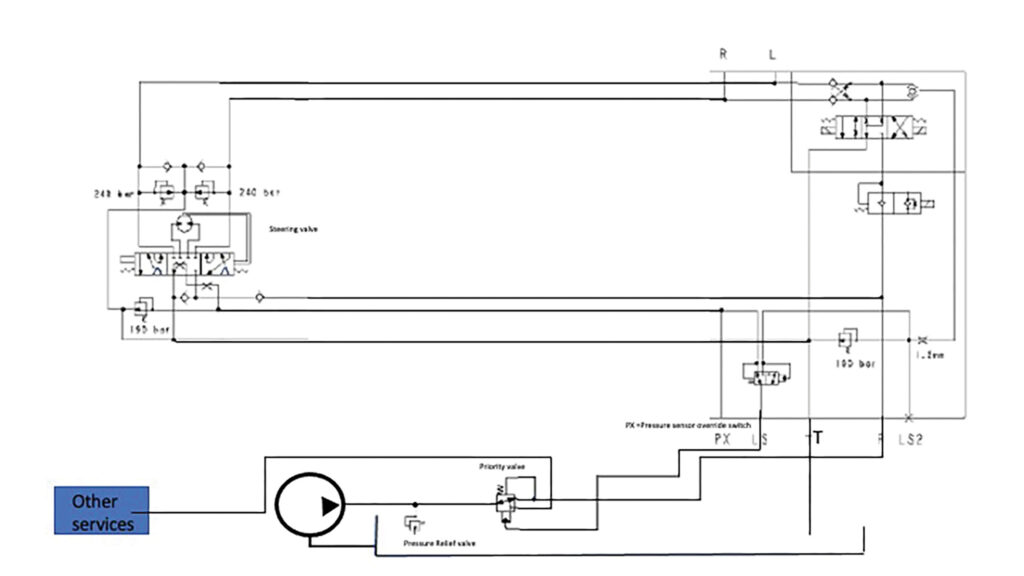

Before meddling with the pipework, Steve drew out a detailed diagram to both make sure it would function correctly and help troubleshoot any problems in the future.

© James Andrew

Custom wiring harness

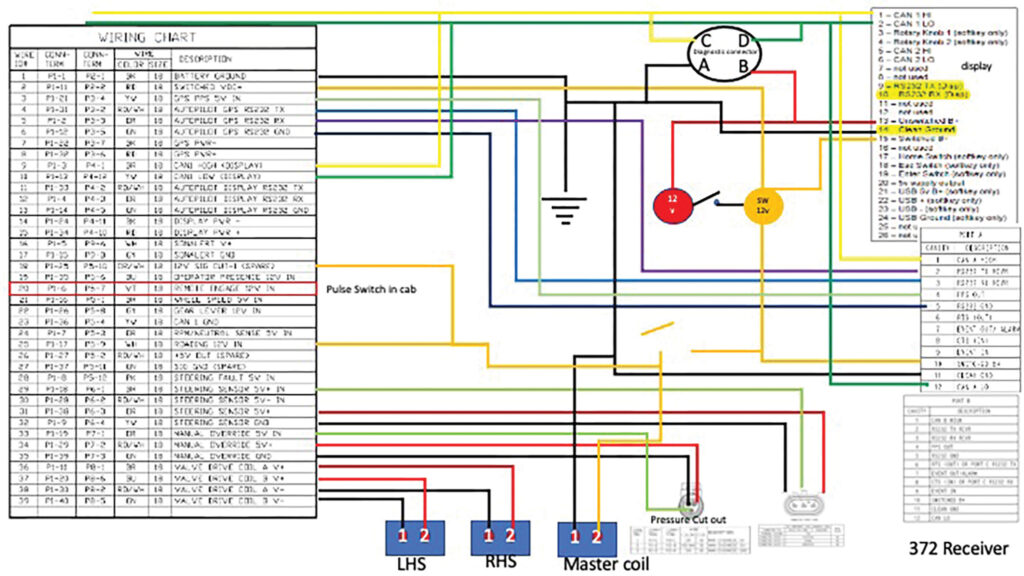

He took the same approach with the wiring loom, which he hashed out on paper before reaching for the soldering iron.

After adding each component, along with its relevant connections, he was able to clearly map out where each wire should go.

Not only did the home-made loom save money – even the twisted canbus wires were made using a drill to wind them together – but it allowed a fully functioning system to be created out of a smorgasbord of non-standard parts.

© James Andrews

Most notable of these was the use of a cheap, bog-standard potentiometer to gauge steering angle, rather than a pricey original from CNH/Trimble.

Although this was more than adequate for the job, Steve needed to tinker with software in the nav controller to convince the system to recognise it.

In addition, a few more minor adjustments had to be made so that the whole lot would resign itself to the fact it was working on a 1990s sprayer rather than a tractor from the 2010s.

Steering angle potentiometer © James Andrews

Auto section control

The final technological upgrade was adding a Dickey John IntelliAg auto section spray controller.

Thanks to this being isobus compatible, it could simply be plugged into the Pro700 screen, with its control readout displayed in one of the tabs.

That said, more custom wiring was required, along with some upgrades on the spray line.

Originally, the Atlas came with four manual sections controlled by simple rotary valves.

Though slow to engage, these were solid and reliable, so they stuck with them, rather than upgrade to snappier solenoid units.

© James Andrews

However, they did add two more to make the most of the Dickey John system and reduce the amount of overlap on headlands.

There was a problem, though. When the section controller was wired straight into the valves, they would rotate endlessly causing the spray line to pulse on and off.

This was solved by adding a separate solenoid to trigger each section. These, along with the brains of the control system, were housed in a custom box positioned on the back of the boom.

Using it

The system has been in use for five years and has barely skipped a beat. Not bad considering it cost less than £5,000 to put together.

The only challenge at the start was dialling in the timing of valve openings to make sure there were no misses or excessive overlaps.

This process was made more difficult due to the delay of the rotary valves switching on. But, since then, very little meddling has been required.

Engagement of the autosteer system is carried out by pressing a button on the screen, but plans are afoot to add an additional switch, possibly pedal operated, that will make it easier to activate.

The hope is to couple this with the four-wheel steering which, though handy for performing neat headland turns, reduces accuracy while spraying in straight lines.

Once perfected, one push of the button or pedal should activate autosteer and turn off four-wheel steer as the machine sets off on a run, with another push doing the opposite so it can loop around on the ends.

Most of the work David and Michael carry out with the Atlas is applying their own blend of liquid seaweed and Bio-N fertiliser to grassland (see Custom Keenan seaweed mixer).

For this, the system has been invaluable for improving efficiency.

It also works well on their own arable ground, which they drill without tramlines, leaving the sprayer to put in its own wheel marks.

For any customers that have established them with the drill, steering is still a manual affair.

As for the correction signal, this comes from free-to-access satellites such as Egnos, which have proved ample for their needs.

“It would be simple enough for us to upgrade to RTK, but we’re in fields for such a short period of time that satellite drift doesn’t make any difference,” says Michael.

In addition to seaweed work, the Atlas applies liquid nitrogen and regular agrochemicals on both their own farm and those of local customers.

A limited top speed of 30kph makes it tedious for jobs further afield which, instead, tend to be carried out by an 18m Case IH mounted sprayer fitted to their Massey Ferguson 6290.

Despite its age and the 9,000 hours on the clock, they’ve got no plans to move the Atlas on.

Packing a 170hp, six-cylinder Perkins engine, it’s got ample power for tackling steep slopes.

The hydraulic suspension means the ride is perfectly comfortable, and the spray pack – 2,500-litre tank and 24m boom – is well sized for the work they carry out.

Like any ageing machine of this type, the Poclain hydrostatic wheel motors can give up the ghost, but these are simple enough to replace at a cost of about £3,000 each.

Thanks to huge, balloon-like 700mm tyres and modest weight it floats well in wet conditions.

The only trouble is that the bar treads are short on traction, so some surer footed rubber with tractor cleats is on the shopping list.

Custom Keenan seaweed mixer

© James Andrews

The core of the Edwards family business, Edwards Agricultural Supplies, is blending natural seaweed-based fertilisers for a wide range of uses.

For grassland, arable and horticultural use, they mix concentrated liquid seaweed – farmed in the North Sea – with humic acid and water to create a product that can be applied with a conventional crop sprayer.

Once on the field this is claimed to stimulate plants into making more efficient use of available nutrients, as well as improving their defences against fungal infection and insect infestation.

Typically, seaweed applications are teamed with another product called Bio-N, which contains a high concentration of nitrogen fixing bacteria.

The role of this is to give a continual supply of nitrogen for up to nine months, without the risk of nutrients leaching away.

Other blends include natural animal supplements for improving gut health and reducing methane emission, as well as seaweed-impregnated wool mats for protecting and feeding trees or shrubs.

These products are supplied throughout the UK, meaning many thousands of gallons have to be produced each year.

Blending process

Originally, the blending process was manual and backbreaking using hand-held paddle mixers to produce batches in individual IBCs.

But a steep rise in demand forced them to think bigger. Inspiration came from an old Keenan mixer wagon, which they could see had the makings of an excellent batch blender.

“The problem with vertical mixers is that they keep throwing the solids to the outside, but with a horizontal beater gravity is always keeping them in the mix”, says David.

To test the theory, Michael knocked up a prototype out of an old oil drum and, satisfied with the result, got in touch with Keenan.

Its engineers then set to work adapting the design of their largest ProMix machine to suit the task.

As there would be no fibrous materials to chop or unload, they removed the knives from the body, as well as the auger and unloading system.

Waterproofing was the next task, with all openings in the tub welded shut and custom seals made for each end of the rotor.

They also added a hydraulic lid that can be opened for adding bags of granular humic acid and closed to prevent liquid slopping over the side during mixing.

A series of 150mm ports were added in the top of the wagon so that concentrated seaweed juice and water could be pumped in, as well as four outlets with hydraulic gate valves in the base.

Currently, just one of these is used to fill IBCs by hand, but the plan is to extend the shed housing the mixer so that it can discharge into four simultaneously.

Due to the weight of the mix, and the fact that it doesn’t need to be moved, the Keenan sits on legs rather than wheels.

Michael also built a platform with stairs, putting the operator at just the right height for loading.

Ideally, it would have been driven by an electric motor, but with no three-phase supply on the farm it was far too expensive.

Instead, one of their two International 955s or a 574 provides pto and hydraulic power, with an extraction pipe whisking exhaust fumes out of the shed.

Prior to the Keenan, manual production maxed out at about 2,000 litres per day with two members of staff putting in some serious graft.

With it, one person can easily mix a 10,000-litre batch – enough to cover 2,000ha – with two achievable if needed.

Loading of the constituents has also been made simple thanks to Keenan’s InTouch controller, which automatically weighs in each product.

Despite the efficiency of the mixing, it still takes about four hours for the humic acid to fully incorporate into the solution.

But the machine can be left to its own devices, freeing up time for them to carry out other tasks.

Packing is the final part of the process, where the seaweed is filtered before being piped into 10-litre containers or 1,000-litre IBCs ready for dispatch.