Novel home-made trommel separator handles sand-laden slurry

© MAG/Oliver Mark

© MAG/Oliver Mark Farmhouse washing machines have a tough life, but Cornish contractor Kevin Heywood took the abuse to new heights when testing his concept for a unique slurry separator.

Rather than oily overalls and straw-pricked socks, he slung in a bucketful of pig slurry before setting the machine on its spin cycle.

The aim was to see whether the whirling motion would successfully split the solid and liquid fractions, the former remaining in the drum and the latter exiting through the mesh.

See also: Thompson Brothers’ bespoke umbilical slurry pumping trailer

And there was good reason for his experiment.

“We’ve found lagoon slurry has been getting much thicker over the past five years, as farmers have been encouraged to divert clean water away from stores,” Kevin says.

Kevin Heywood (left) and Alan Gilkes © MAG/Oliver Mark

“This poses us major problems when it comes to spreading it with an umbilical system, such that we’re often having to dilute it first to loosen it up.”

As well as being a challenge from a contracting perspective, the ultra-viscous slurry has also been costing customers money.

For starters, they’re having to cough up for the extra pumps and tractors required to push the gloopy slop out to fields and, with output often reduced, the service works out to be more expensive on an hourly rate.

Plus, the slurry is liable to dry into a hard crust on the surface, meaning it ends up being harvested with the following crop, to the obvious detriment of fodder quality.

Though separating the material adds a secondary slurry management cost, to the tune of £100/hour for Kevin’s MST400, it eliminates all the aforementioned problems.

Better still, it both frees up valuable space in the main lagoon and gives farmers two different yield-boosting products – a nitrogen-rich liquor to invigorate leys and a heap of solids to increase soil organic matter.

Starting the project

Almost all the manufacturers in this field offer screw press machines, something Kevin was keen to steer clear of.

“90% of our customers bed on sand,” he explains. “And, as good and efficient as a screw press is, it would wear out far too quickly and we’d never be able to price it affordably.”

Comparatively, his trommel-style rotary screener can cope with sandy stuff – and any other bedding material.

As this means of separation is relatively untried on slurry, Kevin first conducted some R&D using the old washing machine to ensure it would reliably separate solids from liquids.

The next step was to work out the most effective mesh size for the drum. Too big and fibre would remain in the liquid, too small and it would kill output.

To do so, he assembled a larger – but almost as cheap – test bed by welding together two mesh-clad 40gal oil drums mounted on roller bearings.

These were friction driven by an old wheelbarrow wheel attached to the output shaft of a dinky petrol engine.

This gave him the chance to experiment with different meshes on a relatively small scale and, as it was mounted on a skid unit, on slurry at different farms.

Rollers squeezing out any remaining juice © MAG/Oliver Mark

Going big

It was another 12 months before the full-scale project kicked into life, when Kevin spotted an old Swedish-built TIM TS-2000 topsoil trommel advertised in Plymouth for £4,500.

“It had been sat in the bushes for several years and was completely rotten.

“I’d only planned to raid it for donor parts – the hydraulic pump, engine and drum – as it was a bit bigger than I’d wanted, but after getting it back to the yard we decided we’d use it as the base of our machine.”

First on a monster list of modifications was to breathe new life into the chassis.

This started with realigning the axles, which had originally been offset by 100mm to account for the weight of the elevator slung to one side.

The straight chassis rails also needed attention, as they left the drawbar far too high to be carried on a tractor’s pick-up hitch.

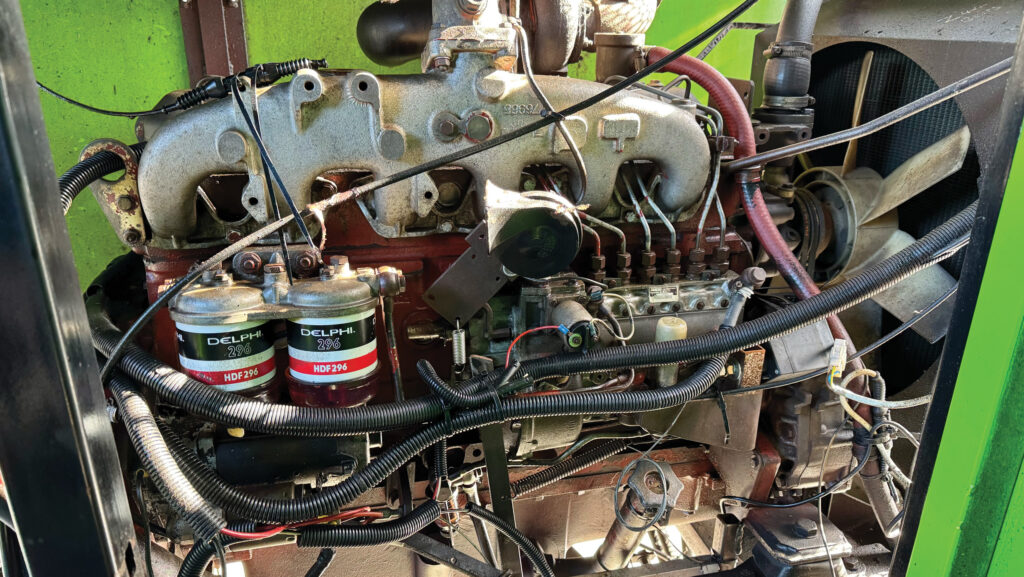

Chopping them one-third of the way back and stepping them down by about 600mm solved the problem, while simultaneously forming a neat platform for the 130hp straight-six Iveco power unit.

How it works

Slurry is pumped into the front of the trommel, which can be set to turn at between 60 and 100rpm depending on the viscosity. A knife gate controls the feed-in rate.

How quickly the material works its way through the drum is determined by its pitch, raised or lowered by a ram on the front and pivots at the rear.

Up to 50% of the liquid is extracted through this churning motion, with the rest squeezed out by two pairs of pressure- and speed-adjustable chain-driven rollers – the top ones rubber, the lower ones mesh.

A lobe pump hidden under the chassis then whisks away the liquor from a small holding bay under the rollers, ideally to a dirty water store on the farm.

Meanwhile, the fibrous element, typically 15-20% dry matter, is sent up an elevator and dumped in a heap.

“We could make it drier,” says Kevin. “But it would significantly reduce throughout and it’s pointless if the material is going to be stored outside.”

Solids are sent up the rear conveyor © MAG/Oliver Mark

Fine-tuning the system

The MST has been extensively fettled as Kevin and operator Alan Gilkes get to grips with the way it works.

One of the first alterations was to replace the Doda pump they originally fitted.

This was bringing in far more slurry than the drum could cope with, such that they were having to recirculate most of it back to the lagoon, so they swapped it for a hydraulically driven Storth Cobra.

This gives greater control, as the output can be dialled down simply by tweaking the tractor’s oil flow.

The new pump is mounted on a tri-stage arm, with three sections of 6in reinforced rubber pipe giving 6m of reach for snaking under slats, dropping into lagoons or stretching over tower walls.

Also incorporated on this front-mounted frame is a reel armed with 200m of lay-flat hose, and a back-up lobe pump to help shift thick slurry beyond the 60m limit of the Cobra.

The trommel has been altered too, with the original hexagonal formation of mesh screens switched to a circular layout that reduces peak loads on the hydraulic motor that powers it.

And, to increase throughput, the four-roller press was recently doubled in width from 600mm to 1,200mm.

“This had been a bottleneck – material was coming out of the drum quicker than the rollers could process it,” says Kevin.

“It was limiting us to about 40cu m/hour, and we want to be close to 100cu m/hour.”

But the hydraulics have been the cause of the biggest Heywood headaches.

After several failed attempts to tweak the original setup, which saw a series of pumps lined on a single shaft, it has now been replaced entirely.

The new arrangement sees the four belt-driven pumps – for the drum, presses, dirty water pump and rear elevator – set in a quadrilateral formation around the engine driveshaft.

These are now sized to suit their respective jobs, so no component should be short of power.

Success?

“The first 300 hours have been a serious learning curve,” admits Kevin.

“The biggest challenge is the wild variations in slurry consistency, which has a massive impact on how quickly and effectively we can separate it.”

“Everyone’s slurry is different, whether it’s the animals’ diet or bedding, or the farm’s storage system, and that can vary at the same site from month to month.”

Most testing is thick, “green” slurry freshly scraped from the shed floor, as it’s warm and slimy, with the consistency of wallpaper paste.

As a result, outputs are a fraction of the 120cu m/hour possible in a relatively wet mix that has settled for a month or two.

To maximise performance, Kevin and Alan are hoping customers will adapt their slurry management to suit the needs of the separator.

Most importantly, this means avoiding overfilling lagoons, which gives plenty of scope for mixing in extra water to loosen it up, and having dirty water storage to pump the extracted liquid into.

Though some customers will inevitably look at separation as a means of “firefighting” brimmed lagoons by freeing up storage space, says Kevin the biggest benefits come later in the season.

“Customers are left with two separate products they can use in a targeted way, rather than sacrificing fields purely to get rid of slurry in an emergency.

“The nitrogen-rich liquid is absorbed quickly and nothing is left on the leaf.

“Plus, the solids can go on springs crops to help build organic matter.”

A front-mounted Storth Cobra pump sucks up the slurry © MAG/Oliver Mark

Next steps

The final trommel mod is to fit an air compressor to help clean the mesh as it turns.

But Kevin is now toying with the idea of adding an auger separator to extract sand from the slurry – a project that could potentially save customers a fortune on bedding materials.

“Based on calculations I’ve seen, a 500-cow herd might be using 6t of sand a day at £20/t. If we could recover 75% of that then customers could save £33,000 a year – assuming it’s fully reusable.

“So, although, separating slurry adds an expense, it should more than pay for itself over the course of a year.”