Scots inventor goes contracting with home-made spot-sprayer

© James Andrews

© James Andrews In 2021, Lanarkshire-based engineer Colin Taylor revealed an ingenious spot-spraying system that can identify weeds in grassland and treat them with a targeted dose of chemical.

Just like high-end setups from the likes of Bilberry and Carbon Bee, his Rumex device uses artificial intelligence (AI) to determine the difference between desirable plants and troublemakers such as docks and thistles.

However, unlike the big-name marques, it is built using affordable components so it doesn’t cost the earth. The system is also modular, which means it can be adapted to fit any width of sprayer, simply by adding more cameras and computers.

See also: Simple 24m mounted sprayers for less than £30,000

Mr Taylor’s long-term plan is to partner with a manufacturer or investor to build and sell retrofit kits under his Taylor Technologies brand.

But for the time being, he is offering a contract spraying service to interested farmers.

To do this, he has converted his original 12m Hardi tractor-mounted sprayer into a trailed machine that he can pull behind his Polaris UTV – an outfit that is light enough to be carted around behind a pickup.

Colin Taylor © James Andrews

Most of his customers are situated in Lanarkshire and south-west Scotland, but the portable nature of the setup means he can travel further afield.

Prices are higher than that of conventional contract spraying, but Mr Taylor says this is far outweighed by the chemical savings, which currently average about 77%, or £47/ha.

Herbicide is applied at the full label rate, but the saving comes from the fact it’s only the target weeds being hit.

Healthier grass

Other benefits are that clover isn’t harmed and grass remains healthy. “As there are few clover-safe chemicals left, blanket spraying of fields kills it off,” says Mr Taylor.

“Because the Rumex system only sprays the weeds, the clover is untouched, as is most of the grass.”

As a bonus, he is also able to create a map of sprayed weeds, desirable species and poor-performing areas to help with future agronomy decisions.

Mr Taylor started working on the Rumex sprayer in 2017, after neighbouring farmer Jim Struthers expressed an interest in a more targeted way of tackling his grassland weeds.

Work began as part of his masters degree in agricultural technology at the Royal Agricultural University and continued alongside his full-time job.

He then founded Taylor Technologies so he could spend more time perfecting the design and providing freelance technology services to other firms, particularly computer vision.

Seven boom-mounted cameras identify target weeds © James Andrews

How it works

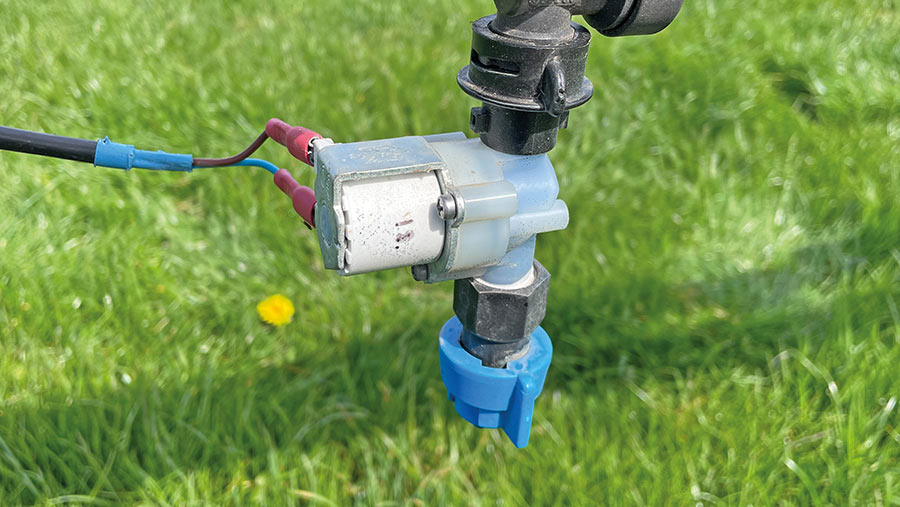

The Rumex spot-sprayer contains three main elements – a series of boom-mounted cameras to take images of the crop, an AI system that identifies the weeds, and a set of nozzles fitted with solenoid valves to apply the chemical.

Once the AI system has analysed the images and decided to spray a weed – a process that takes a fraction of a second – it sends a signal to the relevant valve so it opens long enough to hit the target.

The physical elements of the sprayer took a while to perfect, but the most technical part is the AI – also referred to as a neural network – working away in the background.

This is because it needs to be taught how to identify a particular weed from its colour, texture and shape, just like a human would.

Several computers and displays are used to control the prototype system © James Andrews

The training process shows the neural network thousands of images, all of which are tagged in a specific way.

Unlike a human, it has an almost limitless capacity to absorb these images, so the more that are loaded into the system, the more accurate it will be.

By the time Mr Taylor got Rumex to the prototype stage it had been trained on a dataset including about 20,000 images – a year later this has risen to more than 1m.

This is a huge amount of information to store in its memory but, cleverly, it doesn’t need to. Instead, just the system’s ability to detect images is held on the sprayer’s computer, rather than a huge library of pictures.

This means only a small amount of memory is required and it can make decisions incredibly quickly.

© James Andrews

The images for the database are gathered using a separate camera mounted on the front of the UTV that records video as it drives along.

This is then separated into individual frames, which are manually labelled. Some will be grass, some will be clover and some will be the target weeds.

There is also a sizeable library of cow pats, says Mr Taylor.

“You’ve got to show it what they are so it doesn’t spray them – I reckon we’ve got one of the biggest collections of cow pat pictures around.”

To get the neural network working effectively, Mr Taylor enlisted the help of Tom Reader at Alver Valley Software, who specialises in machine learning and computer vision

A bank of LEDs indicates when each sprayer section is active © James Andrews

Target weeds

Originally, the system was designed to target docks and it has a huge library dedicated to this weed.

As a result, accuracy of identification is near 100% for plants that are large enough to be affected by the chemical.

It is also effective at identifying thistles, nettles and ragwort, with some efficacy on dandelions and chickweed.

In theory, it can identify any weed if it has enough images, but those that are close in appearance to desirable species are the most challenging.

“For these you need an even bigger database of images, so it takes considerably more time and expense to make it accurate,” he says.

In future, he hopes to offer a system that can operate in more crops and environments than just grassland.

Solenoid valves offer individual nozzle control © James Andrews

Mapping

Mr Taylor’s custom mapping software integrates into the Rumex system to form a detailed map of sprayed weeds and other field variables such as clumps of clover, thin patches of grass and poached areas.

This creates an overall picture of the weed burden and provides a basis for variable-rate reseeding of clover or grass.

“Planting clover is expensive, so it makes sense to protect what you’ve already got and reseed only in areas where it is needed,” he says.

He’s also working on what is thought to be the first dedicated clover recognition software, which will be trialled in late 2022.

The final part of the system is a GPS autosteer setup for the UTV. This was created using AgOpenGPS software, an off-the-shelf antenna and a motor that attaches to the steering wheel.

Next steps

Now that the design has been perfected, Mr Taylor hopes to find a suitable partner that can help take the system to market. This could be a manufacturer, or an investor that will enable him to scale up production.

The ultimate plan is to offer affordable retrofit kits that can be installed on existing sprayers by agents or tech-savvy farmers and contractors.

His current arrangement uses multiple computers and screens, but this will be simplified by the time it gets to market, possibly so there is just one display.

In the shorter term, he’s considering building a small number of sprayers for people who are interested in offering a contracting service like his

(see “Contracting rig”).

Colin Taylor uses his trailed spot sprayer to offer a mobile contracting service for farmers © James Andrews

Contracting rig

Colin Taylor’s original prototype Rumex system was fitted to a mounted Hardi 600-litre sprayer with a 12m boom.

It worked well, but he needed a more portable setup that he could tow behind his pickup. The answer was to convert it into a trailed unit that could be pulled by his Polaris UTV.

To help it follow the ground smoothly, he designed a walking beam chassis with four ATV tyres that ride over undulations and keep it well balanced.

© James Andrews

Other modifications included adding a Briggs and Stratton petrol engine at the front of the drawbar to run the pump, a suction hose so that he can fill from tanks, and a series of LEDs to show what the sprayer is detecting.

Red lights indicate that a weed has been spotted and green signifies clover. “It’s a handy guide to glance at and make sure it’s behaving as it should,” says Mr Taylor.

Boom height adjustment and folding was already manual, so he didn’t need to factor in hydraulics.

Due to the small amount of chemical required for spot-spraying – about 200 litres at a time – the tank doesn’t need to be filled, making it easy for his UTV to pull.

Working speeds are currently 5kph while he does the final testing, but the system has the capacity to go up to 10kph or more.