Opinion: Can the internal combustion engine ever be bettered?

© Dedmityay/Adobe Stock

© Dedmityay/Adobe Stock The year is 2050. Every barn in the country has a photovoltaic roof, every farm a turbine transforming the power of the wind, and fields are alive with the hum of ant-like robot armies.

This vision of an electrically powered agricultural utopia has been popularised over the past decade, yet it remains almost as fanciful as ever.

Rather than fixating on electricity as the primary means of net-zero propulsion, government ministers might find the quicker, easier and more effective answer is already right under our noses – and bonnets.

See also: Will battery-powered farm machinery help meet net-zero targets?

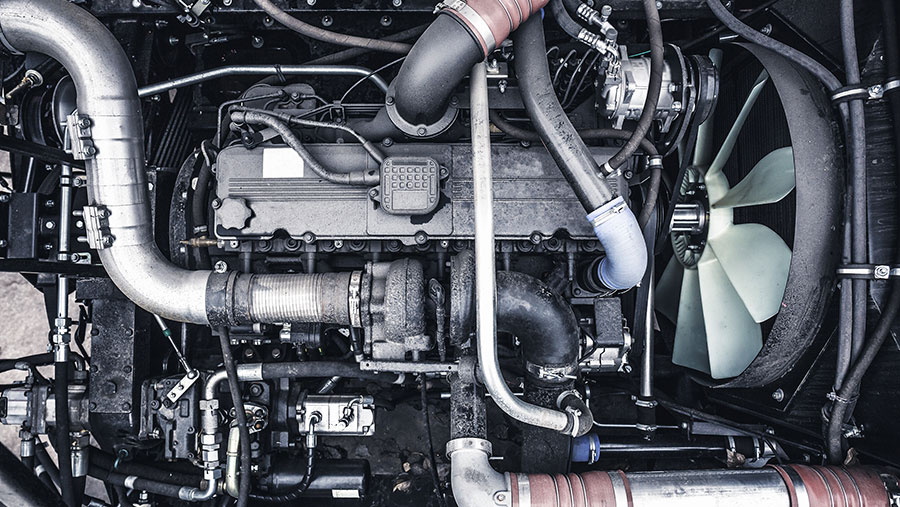

Despite bombastic headlines to the contrary, the ubiquitous internal combustion engine can be just as big a force in the future as it is today.

It seems gross folly to give up on something that has made such immeasurable difference to global food production.

It is efficient and reliable, and is able to serve up abundant power and torque in places devoid of infrastructure. For those with a mechanical brain and a decent set of tools, it’s also relatively simple to repair and maintain.

For proof of its suitability, look no further than the second-hand tractor market, where the most desirable 20-year-old models are commanding prices akin to their original values.

Ironic, really, that in the grip of suffocating emissions regulations there is overwhelming clamour for pre-AdBlue tractors that are free from the shackles of dealers’ laptops and the burden of expensive emissions systems.

Superior technology

Internal combustion is the superior technology and, on current evidence, no electric machinery fleet will compete on performance, price, or reliability.

Batteries are slow to charge, heavy and expensive, and can store relatively little energy.

That’s no problem for routine, stop-start jobs around the yard, but high-horsepower tractors, foragers and combines employed on long, energy-sapping tasks cannot be fuelled on a diet of cucumber sandwiches.

Electric vehicles aren’t as clean as they purport to be, either. Extracting the resources required for an EV powertrain is carbon intensive and production in some countries relies on coal, meaning many electric cars will have to clock up tens of thousands of miles to reach carbon parity with one running a conventional engine.

No surprise, then, that most of the credible agricultural alternatives make use of the time-proven internal combustion engine – albeit with a few modifications.

Synthetic fuel

The simplest answer, in theory, is to ramp up production of synthetic fuel. It is effectively carbon neutral and can be distributed and stored using existing infrastructure.

Hydrogen combustion is being pushed by Deutz and JCB, both of which have built prototype engines with gas injection and spark ignition that deliver performance on a par with diesel (minus the carbon dioxide emissions).

Britain remains slightly behind in the hydrogen power rollout, but the recent energy security strategy committed to doubling the low-carbon production target by 2030.

And only last week, JCB chairman Lord Bamford jockeyed with the Department for Transport to solicit more recognition of the hydrogen’s potential in off-highway machinery.

Capturing and converting methane

Methane propulsion is more advanced still – both in terms of available machines and infrastructure.

Take the work of Cornish firm Bennamann, for instance, which now has a means of capturing and converting methane bubbling off slurry lagoons – thus simultaneously reducing emissions and providing a source of power.

The gas, an undesirable by-product of agriculture, is estimated to have 86% more global warming potential than carbon dioxide, but it is energy dense and, in New Holland’s novel T6.180 Methane Power, there’s a production-ready tractor to exploit it.

Both examples provide compelling evidence that the internal combustion engine has a lot left to give. Agriculture’s battery-powered robot revolution may just have to wait.