Methane-trapping GreenShed – the climate-friendly future of beef farming?

© Tim Scrivener

© Tim Scrivener As the government embarks on the road to net-zero, beef production has fallen under the closest media scrutiny within the livestock sector.

The carbon footprint of cattle is a bone of contention for many, with two-a-penny inflated figures and misinformation leading to wider questioning of sustainability.

To shed a little light, agriculture is responsible for around 10% of the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions, according to Scotland’s Rural College (SRUC). Roughly 41% of that comes from beef, the majority in the form of methane.

Cattle, as ruminants, are defined by their unique digestive system, which produces methane during the fermentation process in their gut, allowing them to digest foods that humans cannot eat.

Looking at carbon emissions through a wider lens, a growing number of organisations are making the shift towards greater environmental sustainability through efforts to offset their carbon, but few are actually changing their practices.

In a bid to directly tackle the carbon footprint of beef, researchers at SRUC have developed a shed that will operate in a circular farming system and capture direct methane emissions from housed cattle.

See also: Aberdeenshire farmer’s retrofit hydrolyser cuts diesel use by 20%

How does it work?

The so-called GreenShed will target the intensive side of the beef finishing sector, and as far as the cattle are concerned, will look, and operate, much like any other.

“We are not changing the production process,” says Dr Carol-Anne Duthie. “There’s a huge environmental benefit from grazing, so we don’t want to take cattle off grass and put them in a shed.”

“But we have an opportunity with finishing cattle as they are already housed. We’re trying to take that opportunity and help the industry where we can.”

With Galebreaker as a technology partner in the project, the shed will be fitted with a curtain-type design which will allow it to be sealed off – not completely, but just enough to create a slight negative pressure.

This ensures that the air inside won’t escape, so that methane directly captured from the livestock can be drawn out with a fan.

Energy needed for the GreenShed will be provided through a combination of solar panels on the roof and the burning of waste materials in an anaerobic digester unit.

This will form a part of a more circular method of farming, with heat produced by the anaerobic digester being used in a vertical polytunnel to produce butterhead lettuce for restaurants.

Though a demonstrator shed will be built from scratch, the system has been designed to be retrofitted to almost any existing farm building.

Who is funding it?

There are 24 projects competing for funding through the direct air capture and greenhouse gas removal programme, administrated through the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS).

If successful in winning funding, the GreenShed will progress to stage two, starting in April and involving the construction of a demonstrator prototype.

The three-year project will allow researchers to verify their models for financial performance, technical performance, supply chains, and greenhouse gas reduction efficacy.

The shed will be built on the SRUC beef and sheep research centre, which sits at the foot of the Pentland hills just outside Edinburgh.

It operates predominantly as a 1,000ha commercial farm, with facilities already in place for capturing and measuring methane produced by livestock.

The test subject is a 400-strong suckler beef herd running two breeding seasons, providing stock year-round to house within the shed.

They graze a mixture of upland, lowland and hill, and once housed, will be monitored for welfare, while seeing how the model integrates into the wider commercial business.

Costs

The anaerobic digester unit is the most expensive part of the build, but the overall price is still an unknown.

“Until we have built it, we can’t give an exact figure,” says John Farquhar, one of the lead researchers on the project.

“Conservative worst-case estimates are in the region of £300,000-£500,000, but this really depends on what the farmer already has on site. If they have an AD unit, you can knock off half the price.”

Operating expenses, maintenance and servicing of components will also add around £10,000-£20,000 to this figure, along with the small labour cost garnered by the vertical polytunnel.

These prices are of course relative, and a recent SRUC study on consumer behaviour found that buyers were willing to pay extra for low-carbon produce.

“There is a reasonable margin that we think consumers are willing to pay for,” says Dr Duthie, “and there’s a definite shift from provenance towards environmental attributes that are associated with products.”

Taking this into account, the economic modelling of GreenShed factors in a 20p/kg premium for the beef – something that equates to a seven-year payback period for farmers without an anaerobic digestion unit.

Those already with an AD unit on site can expect to break even in around three years.

The end result

While the project is still in its infancy and results are yet to be seen, GreenShed is an exciting prospect for producing environmentally sustainable beef, going a step further than simply offsetting carbon.

Considering a vast number of variables, the shed will aim to capture between 60% and 100% of methane emissions from the cattle while they are housed – something that will hopefully equate to a 30% reduction in their overall carbon footprint.

Cornish firm creates kit to convert slurry emissions into fuel

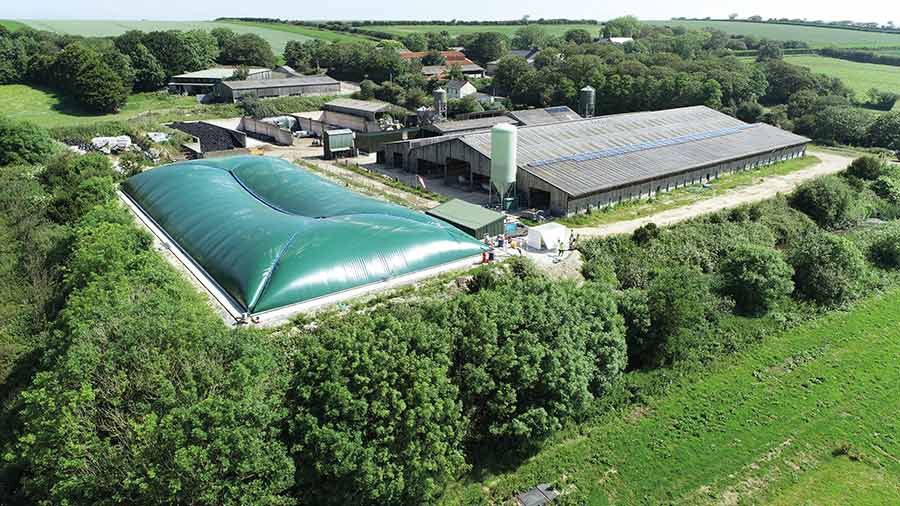

© Bennamann

GreenShed isn’t the first innovation designed to capture and convert livestock emissions into a potentially useful asset.

Bennamann has designed a new type of covered slurry store that collects methane as it bubbles off the top of the liquid.

Once there is a sufficient volume of gas held above the lagoon, a processing truck is brought in to convert it into clean, compressed gas or liquid methane fuel that can be used to power combustion engines.

Bennamann’s lagoon costs about twice that of a conventional earth-bank construction and 30% more than an above-ground store, but the company says the value of the fuel produced means the investment should pay back in four to six years, depending on the size of the farm.

For those who already have a good-quality store, there is a retrofit gas-capture canopy that can be placed over the top with minimal modifications.

The firm’s engineers have also been working on a technique for capturing methane from waste feed and solid manures.

This involves adding water to the material and letting it sit for a couple of days while it forms a slurry, which can then be drawn off into a covered lagoon, where the gas can be captured. The remaining fibrous material can be spread as a soil conditioner or pasteurised and used as bedding.