Machinery Milestones: Safety and comfort revolutionised tractors

Driver safety and comfort are among the top essentials for today’s tractors, but they remained near the bottom of the priority list during the first 100 years or so of power farming history.

Steam engines were the first alternative to animal power, available in small numbers from the 1850s to drive threshing machines and operate cable ploughing systems. The engine manufacturers offered few concessions to driver comfort, and this approach continued after tractors began taking over in the 1890s.

See also: Machinery milestones that changed farming

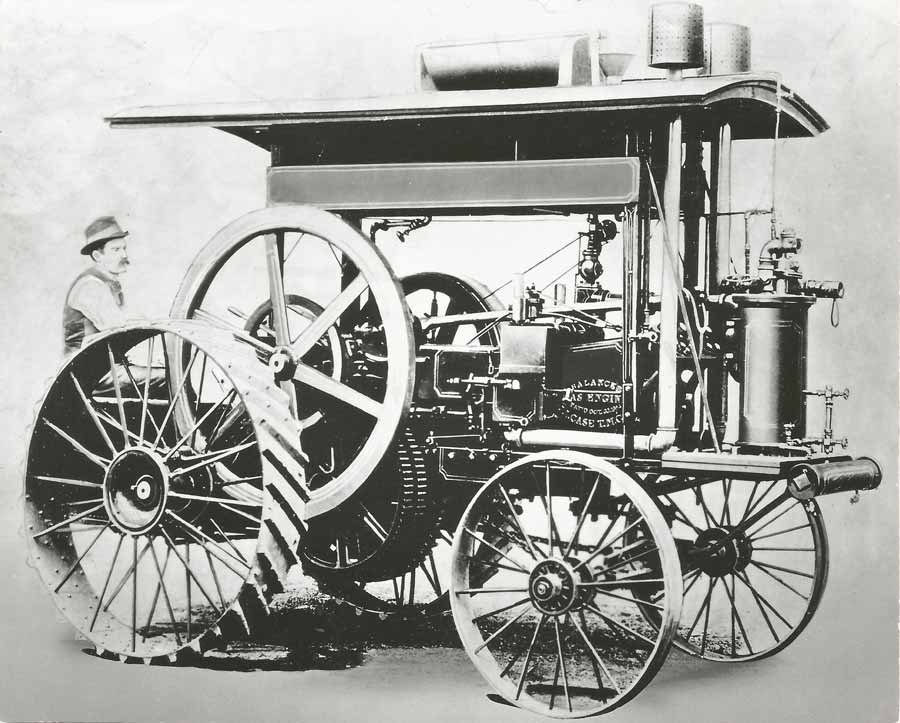

The canopy on this 1892 Case tractor kept the rain off the petrol engine but did not protect the driver

Some very early tractors lacked a seat for the driver, and on others the seat was just a wooden box that also carried tools. Cabs did not appear until the late 1920s, when they were available only on the largest tracklayers, but there were some steam engines and tractors with a canopy providing limited weather protection.

Surviving pictures of one of the earliest tractors, an experimental Case model from 1892 (pictured above), show the canopy extended over the engine, but did not protect the driver.

One explanation for the absence of driver comfort, while trucks and vans were equipped with cabs and padded seats, is that almost all steam engine and tractor drivers previously worked with horses and were used to being exposed to the weather.

Perhaps more surprising is the casual disregard for safety, with operators on the early steam engines and tractors often working within easy reach of hazards such as exposed gears and unguarded spoked flywheels.

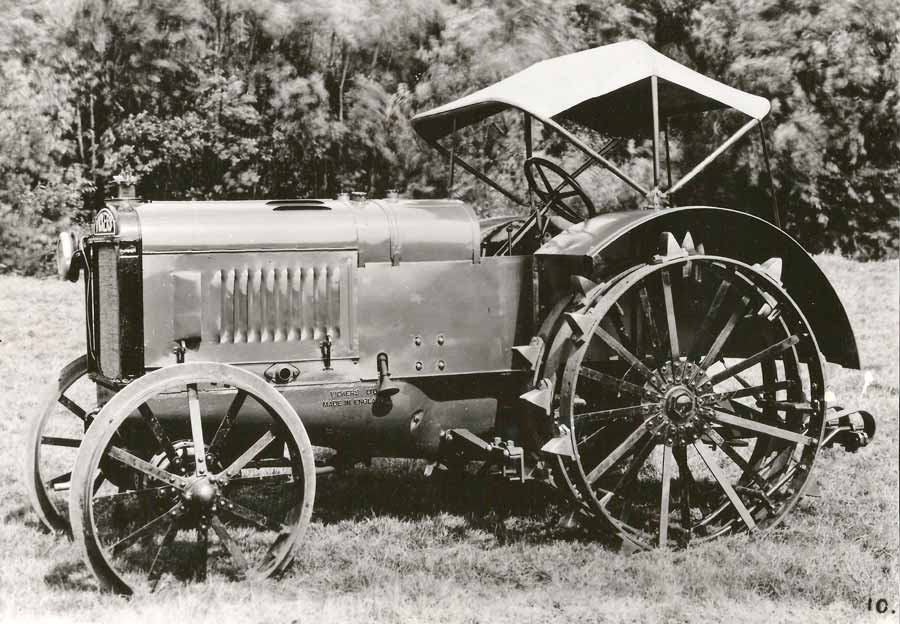

British-built Vickers tractors in the early 1920s were equipped with a sunshade for export to Australia

Safety standards

An example of the lack of concern for driver safety was the brief popularity of the Guide Wheel automatic steering system available in America from about 1912.

This operated while ploughing and it consisted of a frame attached to the tractor’s steering mechanism and carrying a wheel running in the previous furrow bottom.

The Guide Wheel automatically steered the tractor as it turned the next set of furrows, with the driver taking over for headland turns.

This, the makers explained, allowed the driver to dismount and walk beside the moving tractor to check the plough setting or simply for exercise, climbing aboard again to take control as the headland approached.

The popularity of the Guide Wheel faded after a few years, presumably because customers realised the perils of climbing on and off a moving tractor. Evidence that concerns about tractor safety were slowly increasing also comes from the fact that more manufacturers were equipping their tractors with brakes.

Previously brakes were usually regarded as an unnecessary extravagance, which was not quite as reckless as it sounds, because tractors were still on steel wheels until the early 1930s, restricting the top speed to about 5 or 6kph.

The widespread adoption of brakes during the 1930s coincided with the arrival of rubber tyres and faster speeds.

Brakes were still unusual in the early 1920s, but they were included on this 1922 Lanz tractor

Overturned tractors

The biggest dangers facing the pioneer tractor drivers included the risk of injury or death if the tractor overturned, and evidence of the dangers involved was available from a survey in about 1923.

The survey featured the Fordson Model F, the most successful tractor in history with more than 50% of the world tractor market in the mid-1920s. In spite of its popularity, early versions of the Model F had a poor safety record.

The implement hitch point was positioned too high and if a plough or a cultivator hit a solid object such as a rock or tree root, the front end of the tractor could tip over backwards.

The survey found 136 drivers died in Model F overturning accidents on American farms between 1918 and 1922.

Changing the hitch point position reduced the number of Model F accidents, but overturning can occur with any tractor make or model, and the cost in terms of driver deaths and injuries rose as the number of tractors on farms increased.

There was plenty of discussion about the problem, but decisive action did not arrive until the 1950s, with Sweden taking the lead.

Early versions of the Fordson Model F earned a reputation for overturning

Cab safety frames

The rising death toll persuaded the Swedish government to introduce a law requiring an approved cab or safety frame to be fitted on all new farm tractors.

The law came into force in 1959 and during that year, when almost all working tractors had no cab, 34 drivers lost their lives due to overturning accidents on Swedish farms.

The number of tractors in Sweden fitted with a cab or frame reached 47,000 by 1963, and during the four years after the law was introduced, only one driver lost his life in an overturning accident involving a tractor with a cab.

The solitary fatality occurred when the driver, aware that the tractor was rolling over, jumped out of the cab and was crushed, while a passenger who remained in the cab survived with minor injuries.

David Brown was the first UK tractor company to offer an approved safety cab in 1968

After an 11-year delay, Britain followed Sweden’s example, in spite of objections from some customers who complained about the additional cost of the cab and difficulties accessing low-roofed buildings.

A problem that arrived with the new cabs was that they increased the driver’s exposure to noise, and in 1976 additional legislation introduced the new quiet or “Q” cabs with a 90dB(A) noise limit, later reduced to 85dB(A).

Dealers in some areas reported increased sales ahead of both the safety cab and Q cab legislation, as some customers bought early to avoid the extra cost, but this was probably a false economy because the new cabs were popular and depreciation rates were much higher for the cabless tractors.

Renault’s pioneering Hydrostable cab suspension used coil springs and torsion bars to give a smoother ride

Weather protection

Even before the safety cabs arrived, the 1950s had already brought an increasing demand for simple weather protection cabs. They were usually made of canvas and sheet metal, and were sometimes draughty, restricted all-round visibility and gave little or no protection in a major accident, but drivers welcomed the protection they offered from the worst of the weather.

Weather cabs plus safety and Q cabs helped change attitudes to operator comfort and safety. The driver became a key factor when designing a new tractor, resulting in a flow of improvements such as controls and instrument layouts, better seats, ease of access to and from the cab and adding power steering, air conditioning or better sound equipment.

Suspension systems were another big advance including the Renault Hydrostable cab in 1987, followed by JCB’s Fastrac self-levelling front and rear suspension in 1990.

The extra bonus available from advances in comfort and safety can include improved efficiency and productivity. Working a few extra hours to finish a job is more acceptable in a comfortable cab, and the driver is also more likely to select a faster working speed.

There are benefits all round, and the only threat to continuing emphasis on driver wellbeing could be a new generation of driverless tractors.