Machinery Milestones: History of the combine harvester

Threshing machines were an international success story for British manufacturers, and the companies involved became global leaders, but the combine harvester market proved a far harder nut to crack.

Britain’s threshing machine success lasted for much of the 100-year period from the 1840s, and at the peak of demand there was a long list of countries where British-built threshing machines were the popular choice.

In the 1820s, while crops were still being cut with scythes, the search for new harvesting methods had already started.

This was particularly the case in the US and Australia, where large farms often faced manpower shortages while using traditional harvesting techniques, and it was a problem in much of California where the earliest ancestors of today’s combines were built during the 1880s.

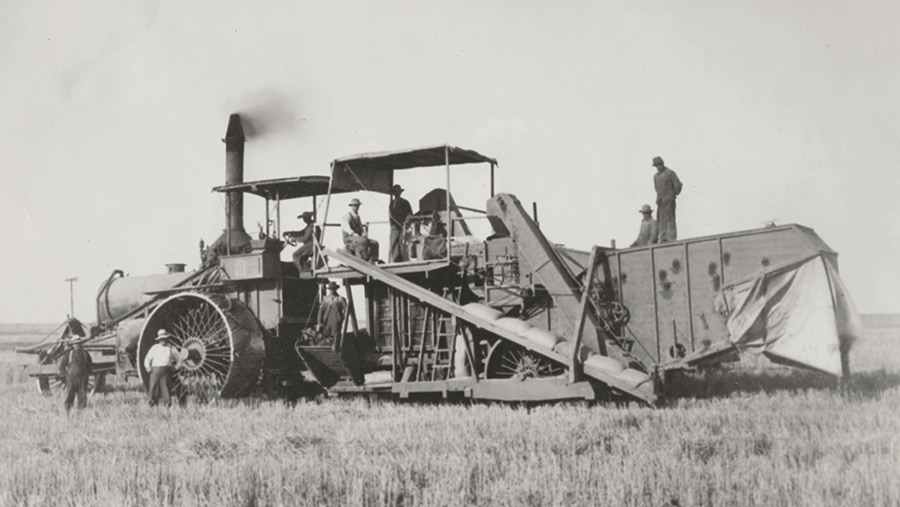

Best combine © Idaho Historical Society

Credit for producing the first Californian combines usually goes to Daniel Best’s company, which started production in about 1885 – narrowly ahead of the Holt brothers, who are said to have built their first harvesters in 1886.

Manufacturing was small scale initially, with most of the combines sold in California at first, and they remained important products for both companies until the early 1900s when they started tracklaying tractor development projects.

In 1926 Best and Holt merged to form the Caterpillar tractor company.

The first harvesters from both companies shared some design features, including horses or mules to provide pulling power, with up to 40 animals on some of the biggest machines.

The combines were developed basically as a threshing machine on wheels, with a bagging-off platform for the grain plus a header that was side-mounted, and the draft animals also powered the threshing system through a ground wheel drive mechanism.

Providing the large team of animals needed to operate the biggest combines probably caused problems for some grain growers, but, fortunately, steam traction engines were introduced in about 1890 as an alternative by both Holt and Best, and by other companies that were starting combine production.

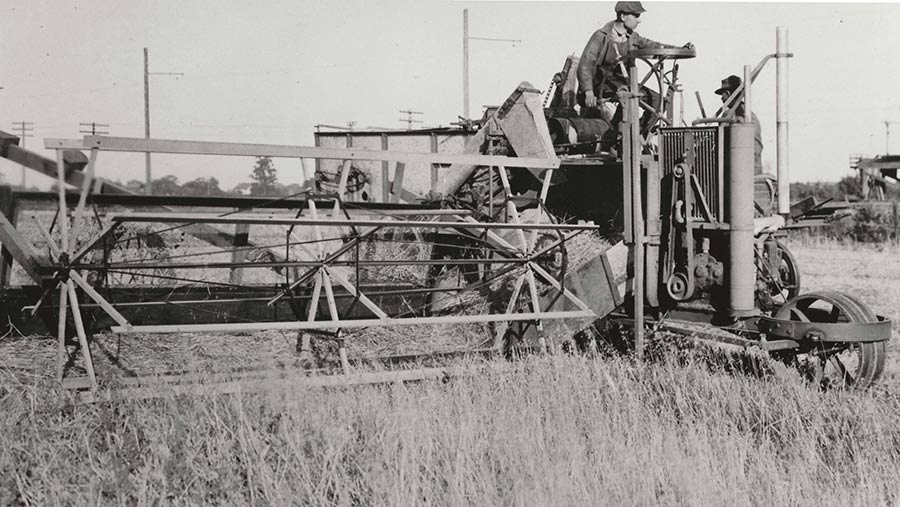

© Mike Williams

Using steam power in a very dry harvest field carries obvious fire risks but, in spite of this, steam became increasingly popular until about 1910 when petrol fuelled tractors arrived to provide more pulling power.

Tractors with petrol engines had been available in America since 1889, but low power output and a reputation for poor reliability during the pre-1910 period may have delayed their arrival in combine harvesters.

Petrol engine © Mike Williams

Wartime development

Tractor reliability had improved when the 1914-18 war brought a major boost for power farming.

Tractors and other equipment were needed to increase farm productivity across the US, Canada and the UK, and this was mainly to make up for the loss of manpower as farm workers were conscripted for the battlefields of Europe.

Britain, in particular, needed to increase home-grown food output to compensate for reduced imports as German U-boats destroyed ships bringing supplies from abroad.

Combine harvesters helped inprove food production efficiency in several countries but this did not happen in the UK, where tractor imports were the priority.

While tractor power was becoming popular on UK farms by the early 1920s, combine harvesters failed to attract farmers or contractors during the war, and the lack of interest continued into the 1920s.

Farm machinery census figures paint a bleak picture for combine ownership, with just four machines working on UK farms in 1930, rising to 10 in 1931 and reaching about 50 by 1937.

It was a time when profit margins were generally low in UK farming, which obviously discouraged investment in high-cost machinery.

The lack of combines also meant increased labour costs at harvest time, though combine ownership could also generate income more quickly by having crops to sell a few days after harvest – an alternative to waiting months for the threshing contractor to arrive.

UK pioneers

Clayton combine © Mike Williams

In spite of almost non-existent UK demand, Lincoln-based Clayton and Shuttleworth decided to become a combine manufacturer after a long history as a leading British threshing machine company, and its combine project started in 1928.

The first of its new tractor-pulled harvesters was built in 1930, but the company was facing serious financial problems and it called in the receiver in the same year.

Its assets were bought by the Marshall company – also a leading threshing machine maker – but the new owners decided combine production had no future and the project ended in 1932 when only five had been built.

The sole survivor is in the excellent harvest machinery collection at the National Museum of Scotland.

While Britain’s only 1920s/1930s combine manufacturing venture failed, the Claas family in Germany showed that European harvester production could be a success.

Its first combine was a wrap-around design available from 1930 to work with a Lanz Bulldog tractor.

First Claas combine © Mike Williams

Claas was at the forefront of introducing wrap-around combines built to attach on and around a specific tractor model.

Small numbers of these harvesters featured in the surge in machinery development following the Second World War, but demand was modest.

Smaller acreage farms that might have been attracted by a wrap-around combine often favoured a trailed machine instead, and many 1950s farmers still chose to use a binder or call in a harvesting contractor.

Claas progressed to trailed combines in 1936 when it began making the first model in its trailed harvester series that became the basis for the company’s post-war recovery.

The trailed combines were joined in 1953 by the first Claas self-propelled harvesters, which led to the Dominator series that achieved long term success following its launch in 1971.

Massey-Harris harvesters

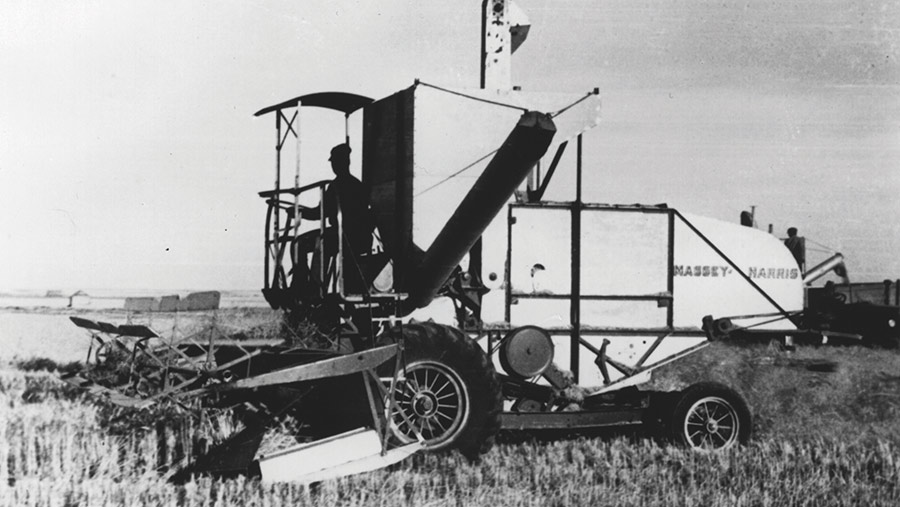

MH21 Massey Harris © Mike Williams

One of the biggest developments in combine history was the introduction of the first self-propelled harvesters from Massey-Harris, which later became Massey Ferguson.

Production of its MH-21 combine began in 1939 and the company held ambitious plans for the future, but the Second World War also started in 1939, bringing with it the emergency rationing for steel and other raw materials needed for making military equipment, thus forcing Massey-Harris to reduce its combine harvester production.

This was a time of increasing demand for combines because of the US wartime food production programme.

To boost production, Massey-Harris guaranteed that if materials were released to build an additional 500 of the new combines, it would ensure that they harvested 2,000 acres each in 1944, providing an efficiency injection at a critical time in the food programme.

The deal was accepted and US farmers and contractors agreed to play their part in the programme, which was known as the Harvest Brigade, with some combines cutting their way northwards from the southern states and ending in the late crops in Canada.

The one million-acre target was achieved and Massey-Harris, the MH-21 and self-propelled combines in general earned a big, patriotic publicity boost.

British boom and US expansion

Britain’s brief surge in combine popularity came after the Second World War ended, and for a few years the results were impressive.

Combines from Ransomes, another former threshing machine maker, achieved success mainly in the trailed sector, the Bamfords brand name appeared on combines imported from Italy and Sweden.

High-output Lely Victory combines were assembled in Britain during the 1960s with a folding header that attracted interest but modest sales.

There was a short-lived trailed combine venture from David Brown, and also from several well-established North American makers including Allis-Chalmers and Minneapolis Moline, which transferred some of their production to the UK.

International Harvester and Massey-Harris produced both trailed and self-propelled combines in UK factories too. Britain was suddenly a favourite location to build combine harvesters, but the enthusiasm soon disappeared, apart from Massey-Harris, which maintained large-scale production in Scotland.

Combine manufacturers in the US enjoyed a big post-war expansion in both sales and technology, and John Deere’s self-propelled No 55 model was part of the success story.

It was designed during the war, ready for production to start in 1946, and had a specification aimed at what was then the medium- to high-capacity sector.

As such, it came with a 12ft cutting width, a 60hp engine powering a four-speed gearbox, was available in both tanker and bagging formats, and had Hillside and Rice variants for special uses.

An indication of the No 55’s popularity, which helped to establish John Deere as the biggest combine manufacturer, is that the standard model remained in production for 13 years.

Some versions were still available in 1969 – an extraordinary 23-year production run.

Performance improvements

Significant technical developments since the war include a rapid switch from spark ignition to diesel engines.

Tracks became available to replace the driving wheels on combines bought by customers, providing reduced ground pressure and a narrower width for road travel, as well as a smoother ride, while rotary separation was an International Harvester development arriving in the late 1970s.

Axial Flow © Mike Williams

Rotary separation replaces the conventional threshing cylinder with one or two rotors located longitudinally instead of transversely to achieve increased separation capacity.

Axial Flow became a major success for International and was followed by other manufacturers introducing their own versions.

An early ancestor of the stripper header harvester arrived in Australia in the 1840s, when the idea of simplified harvesting by removing only grains or grain heads made its first appearance.

The idea is now completely updated to work as a header on a modern combine, with the first production version introduced in the early 1990s by UK-based Shelbourne Reynolds.

Stripper header attachment © Mike Williams

Its stripper header uses fingers mounted on a powered rotor to remove the grains or seeds, leaving the rest of the plant rooted in the ground to be cut and baled or incorporated.

The benefits include a substantially reduced volume of crop material passing through the combine, and increased work rates, with only chaff and occasional straw to be separated.

Improved output

An indication of the faster work rate is the expansion in working width, starting with a 20ft maximum in 1990 and increasing to 42ft now.

Much of the UK stripper header production is exported to harvest crops such as wheat, barley, rice, linseed and grass seed.

Another increasingly popular header development available from some leading manufacturers is a draper version with belts to move cut material to the centre.

This is useful for a wide range of crops, sending them through the combine head first to provide optimum performance with a constant feed.

Cab comfort

For combine owners and drivers, some of the most important developments are the factors affecting performance and operator comfort, and much of the progress has been linked to the arrival of cabs in the 1970s and 1980s.

Enclosing the operator in a sealed workspace allowed equipment manufacturers to offer important developments to manage the cab interior environment with reduced noise levels, dust suppression and air-conditioning.

With the major controls accessible in the cab, the driver can complete the starting procedure and carry out virtually all the operating adjustment without leaving the seat.

A recent development is to allow the combine’s management system to monitor the performance and automatically adjust the settings.

There is often a choice of options to suit field conditions and driver preferences, and for steering the combine the list can include a traditional steering wheel, auto-steer using GPS or a sensor to follow the edge of the uncut crop.

An additional possibility that is currently attracting interest is using a form of joystick steering that can reduce the physical effort required from the operator to complete a headland turn, while the absence of a steering wheel allows a better forwards view.

Another important growth area during the past 20 years or so has been information technology, collecting, storing and using data, and on some of the latest combines this can include yield monitoring linked by GPS to provide information that can help identify problem areas in the field to assist future management.

This automation has taken some of the workload away from the driver during long hours in the field.

Harvesting can be long, tiresome work for operators, but the achievements during more than 130 years of combine development have made the job more pleasant and have vastly improved harvesting output and efficiency.