Aussie contractor converts old bin lorries to bale chasers

An innovative Aussie contractor has designed and built a gang of self-propelled chasers, each one capable of stacking up to 1,600 bales in a day.

Resourceful inventor and keen up-cycler Roley Pearce makes his machines from redundant bin lorries and cement mixers.

He reckons they can collect and stack bales in the field at three times the speed of a regular telehandler and flatbed trailer combination.

Old bin lorry used to build bale chaser

They work by slinging bales over the truck roof and on to a collection ramp, and can piggyback up to 14 4x3ft squares at one time before completing a two-stage offload at the stack.

See also: Farmer saves cash by 3D printing parts for home-built drill

He built his first model 12 years ago, having received a request from a friend that had seen Stinger bale collectors running in the US.

A year later and the first machine was completed, and seven more have rumbled out of his workshop in Beverley, Western Australia, since.

Each one varies slightly depending on the donor vehicle – the biggest have four axles, while potentially UK-friendly versions run twin axles and four-wheel drive

All are built on a modest budget, predominantly from second-hand components, aside from the main steel frame and hydraulic rams.

Mobile Hay Stacker spec

- Engine 275hp-345hp Cummins six-cyl

- Transmission Six-speed Allison automatic

- Top speed 100kph

- Hydraulics Two 80-litres/min pumps

- Total weight 13t

- Typical daily output 1,000 4x3ft bales/day

The beauty of the system is that the wagons can do 100kph (62mph) on the road, which is a necessity given the business’ territory stretches 380 miles from the main base to Esperance on the south coast.

Building it – the driveline

Bale chaser’s driveline

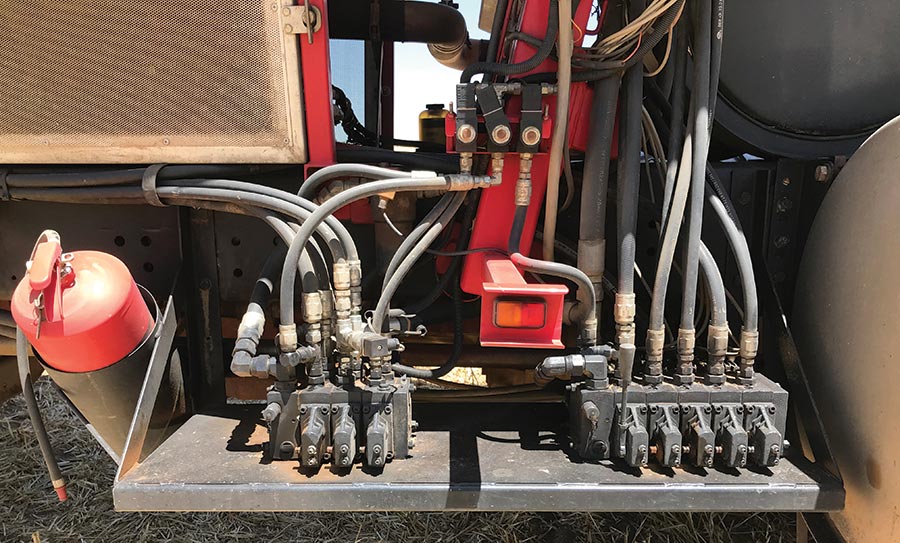

Butchered bin lorries form the ideal base for the chasers because they already have an automatic transmission, big engine and bank of eight double-acting hydraulic valves, keeping manufacturing costs to a minimum.

The Inter Acco tractor unit, or Iveco Accos on later versions, mostly run a six-cylinder, 300hp Cummins engine and many arrive with a surprisingly few miles under their belt.

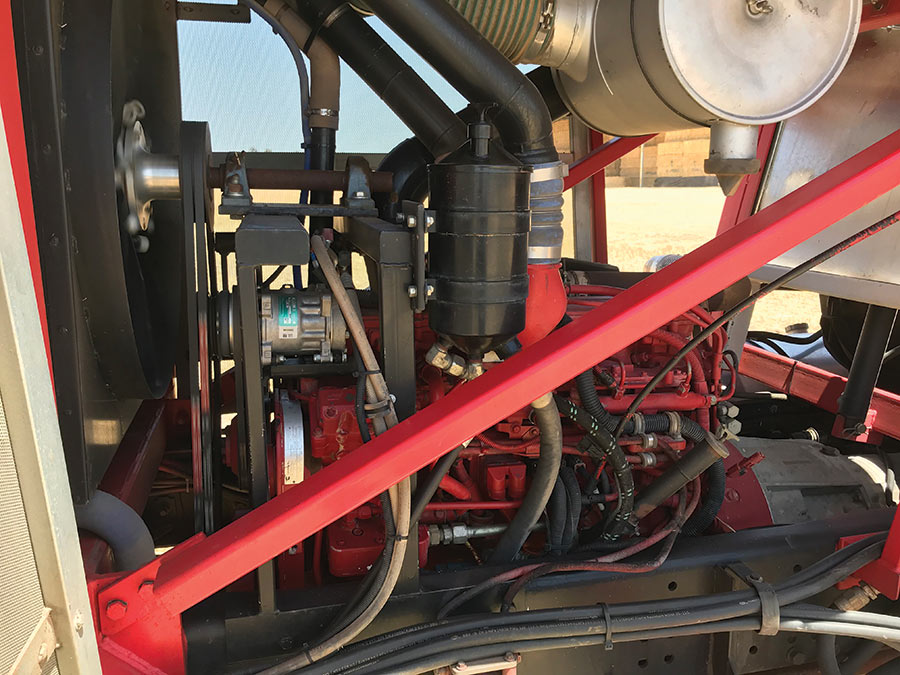

Bale chaser’s engine

The first job in the manufacturing process is to strip off the old body, which can then be used to store all the other redundant parts before it is carted off for scrap.

This strip-down allows good access to the chassis rails, which are usually extended by about 1.5m.

Part of this process involves shifting the differentials – most machines have locakable diffs on both axles – to the back of the chassis.

The last part of skeletal surgery comes in relocating the engine halfway back.

This is predominantly to shift weight to a more stable position as, with some Krone bales weighing close to a tonne, the front axle(s) would otherwise have to burden a total load of up to 9t when fully laden.

This rejig also softens the noise of the engine in the cab.

The block is bolted to the chassis longitudinally and a trio of over-capacity radiators from retired New Holland combines help cool the hydraulics, intercooler and engine in air temperatures that can regularly exceed 40C.

The fan also has an automatic reversing function to keep the bank of radiators clean of irrepressible stubble chaff and dust.

The other notable engine-related fitment is a 650-litre diesel tank.

As the engine rarely breaks 1,200rpm, it’s usually enough for a few days’ work. Hydraulic power is provided by a pto from the engine.

This runs a pair of load-sensing 80-litres/min pumps salvaged from the donor machine that maintains an oil flow to the 1,500psi valve block.

The rest of the driveline remains unchanged, including the sought-after Allison six-speed automatic transmission and air suspension.

The latter’s air supply also powers the bale-catching mechanism (more on that later).

Building it – the cab

Another major piece of DIY manufacturing involves the cab.

Early-generation models simply used the existing assembly, which typically has dual controls (two sets of pedals, steering wheels, etc).

In use, the driver sits “curb side” for easy access to the joystick, but for licencing reasons must switch to the right-hand drive seat on the road.

However, later versions carry a bespoke, square-framed cab with a central driver’s seat and stacks of space in the back for a bed and cool box.

This modified arrangement improves visibility and the joystick is mounted to an armrest with an emergency stop nearby to kill the hydraulics.

All electrics and wiring are replaced, and the air conditioning is upgraded – it’s an essential during Aussie summers and a breakdown is deemed “as important as a flat tyre”.

Building it – the computer

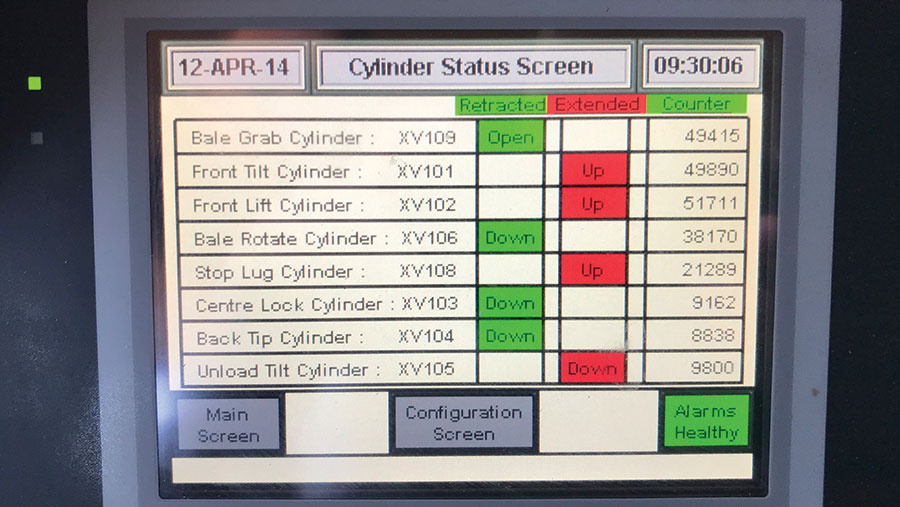

The Hay Stacker’s stand-out feature is its on-board computer and customised Automation Direct screen, which is impressively sophisticated for a workshop build.

Mr Pearce enlisted the help of a computer whizz from Perth to write the software, which is stored on a regular SD card and has remained largely unchanged for more than a decade.

It talks to an array of proximity sensors on the frame and pressure sensors in the hydraulic circuit to automate the loading process, so just a single button completes the entire lifting cycle.

It also has a total bale tally and it’s apparently so easy to use that seasonal workers with no farming experience need just an hour of training.

How is it loaded?

The driver comes to a split-second stop and presses a joystick button to engage the front grab to grasp the bale’s ends.

Once the sensors detect enough pressure on the squeeze (roughly 1,500psi), a pressure sensor in the hydraulic block engages the automatic lift cycle.

This involves hoisting the bale up and over the cab, where it is released on to a 15deg ramp.

At this point, the bale leans against air-activated catching arms, which are powered by the machine’s air suspension compressor.

The weight of the bale slowly forces the arms to retract, allowing it to slide in a relatively controlled fashion down the chute.

Pairs of nylon strips protrude from the chute by 40mm to form a slippery surface, allowing it to slide unopposed.

The first bale settles at the base of the chute, held from falling to the ground by a row of four tines.

To avoid saggy bales catching as they slide, the central section of the tin chute is formed in a V-shape.

And an extra pair of restraining tines can be fitted to hold soft 4×4 bales that would otherwise push through the forks.

The loading process takes roughly 15sec per bale and, once the lift cycle has repeated seven times, a wide centre lock automatically pops up in the middle of the chute.

This holds the weight of the next batch of seven – once these are on-board, the front grab stays in the lifted position to prevent overloading.

What about unloading?

Unloading is engaged by pulling the joystick back while pressing the unloading button, which causes the front grab to drop down to balance the rear weight.

The first part of the unloading process engages a set of kicker rams. These push the top three of the seven-bale set upwards by about 40cm to form a staggered stack that should be safer and more weatherproof.

Once this is done and with the machine backed touch-tight with the stack, the bottom half of the chute moves to its upright position to offload.

The machine then pulls forward, lowers the chute and retracts the centre lock, allowing the second batch of seven to slide to the bottom ready to complete the process again.

When forming the first part of the stack, the operator can trick the computer into thinking it has more bales on-board.

This helps create a safer, pyramidal shape to avoid the whole lot toppling over.

Is it possible to collect different sized bales?

Cleverly, the machine can be adapted to suit different square bale sizes – either 8x4x3ft or 8x4x4ft.

Once the size has been selected on the touchscreen, the position of the grab is automatically adjusted from 60cm to 80cm above the ground.

Most models have capacity for 10 4x4ft bales, which turn in the lifting arc so that the top side in the field becomes the bottom on the chute. This means they end up stacked on their sides.

For 4x3ft bales the process is slightly different.

Capacity is 14 bales, but a flipping mechanism above the cab roof turns them on their side on the chute, so they are stacked string side down when unloaded.

The abundance of moving parts means there are roughly 60 daily grease points, covering the pivots on the front, tipper, kicker, bale rotating system and suspension.

Pre- and post-season repairs and improvements take another three months of the season.

Mobile Hay Stackers

Having cut his teeth building sheep feeders and header trailers, Roley Pearce’s niche bale collecting operation, which he runs with his daughter Jules and son-in-law Angus, has rapidly expanded to cover farms across the southern half of Western Australia.

Stretching from Esperance to Perenjori, it shifted a whopping 250,000 bales last year alone.

The season starts with hay in September and, with yields topping 10t/ha in productive areas, the team of eight is kept busy through until the arable harvest.

The sugar content of crops is particularly high, which makes them a desirable export commodity to dairy, beef and racehorse industries in Asia.

However, this also provides challenges, with collecting and stacking only really possible in low-moisture daylight hours, when the bales are less sticky and slide down the chute smoothly.

The straw season runs through to the end of harvest in February and average straw yields are 4t/ha, though likely to be down by as much as 50% this season due to drought.

Sadly, though, you can’t currently buy one of the company’s Hay Stackers – it has only sold the original version and is reluctant to sell any others given the challenge of warranty and service on machines built predominantly from recycled parts.

However, with increasing interest from farmers across Australia, there are plans afoot to begin manufacturing from all new parts.

Mr Pearce also has a prototype design up and running that stacks pairs of bales on the chute.

It uses chain-driven forklift tines to control them as they fall and the perk is that the full 14-bale load can be unloaded in one go.