How a Wiltshire-based mechanic built his own hedgecutter

© James Andrews

© James Andrews Luke Compton likes a workshop challenge, so when he needed a new hedgecutter he decided it would be far more satisfying to build rather than buy one.

Complex geometry and powerful hydraulics make these machines a daunting prospect for farm-level fabrication, but the Wiltshire-based mechanic eased himself into the task.

The model we’re featuring here is Luke’s second home-spun trimmer, having made a makeshift one a few years ago out of a Palfinger HGV crane.

See also: Staffs contractor rates Shelbourne’s ‘head memory’ hedgecutter

Though this was assembled on a shoestring budget using parts scavenged from the family farm near Bradford-on-Avon, it went together like a charm and gave years of loyal service.

On the back of this success, he decided to push the boat out for the second, custom building it from scratch using mostly new metal.

He didn’t scrimp on the functions either, with twin rams for adjusting height and angle, head tilt, power slew and a 5m telescopic arm.

To get a good quality finish, Luke also went to the trouble of upgrading his workshop, investing in a second-hand Colchester Triumph lathe and an Avonmouth milling machine.

Luke Compton © James Andrews

Timber patterns and jigs

Before any metal was cut, he built a series of MDF patterns to test the geometry and refine the shapes of the profiles.

These were then transferred to the stock steel and he traced around them using his plasma cutter.

On his original machine, the geometry worked out perfectly first time, but for this one he had to make a few adjustments after it was first tacked together.

“It’s annoying that it happened when I was trying to do a tidy job, but you don’t really notice the alterations now it’s been painted,” he says.

All the main pivot points came out nicely though, with the bushes machined on the new lathe and holes in the outer plates drilled accurately using the milling machine.

The telescopic arm also went together as planned, fabricated from 4in and 5in box section steel, with the inner section running on replaceable nylon guides.

Even the 1.2m flail head is all Luke’s work. This was made to accommodate Bomford L-shaped flails and he started by making up a jig to get all the lugs correctly positioned.

Once these were tacked in place, he ran the rotor up on the lathe and balanced it well enough that it runs at full chat without any significant vibration.

There’s also a hinged hood flap, allowing him to alter the size of the opening according to the amount of growth he needs to take off.

The only parts of the skeleton he bought in were some of the pins, which came from Kramp, plus bearings and some of the smaller bushes that he sourced from Simply Bearings.

© James Andrews

Hydraulics

Although he splashed out on the metal, Luke prevented costs from spiralling by pilfering many of the hydraulic components from old machinery.

The pump for driving the flail came courtesy of an old Sanderson 724 telehandler that he was breaking for spares, and he managed to repurpose a JCB Loadall steering pump to power the rams.

This came out of a scrap bin and after some new seals it was good to go.

Getting both pumps to run off a pto did require some work. He managed to find a second-hand Bima gearbox that would do the job, which was a bargain at £100 – new ones are about 10 times that price.

However, he had to both mill down the pump shafts and bore out the gearbox flanges to successfully marry them together.

Piping up the machine was made simpler by the fact he could use the crimping machine at work – he’s a mechanic at Chandlers’ Cirencester depot – and he kept the plumbing as straightforward as possible.

This meant forgoing an oil cooler, which he didn’t deem necessary for the amount of work he would be putting its way.

That said, he built the oil tank with plenty of capacity – 80 to 100 litres – so there’s more than enough volume.

Overheating hasn’t been a problem, but the fact that both pumps run off the same tank feed means there has been some cavitation.

It doesn’t seem to affect performance, but he might cut an extra hole in the tank to give them dedicated oil flows.

Other scrap-bin freebies included a Bomford flail head motor, which he managed to resurrect with some new seals. He gave this a belt rather than direct drive, meaning it sits neatly at the back of the head.

Hydraulic rams were scavenged from various old machines, including a muck grab and a Krone rake.

© James Andrews

Cable controls

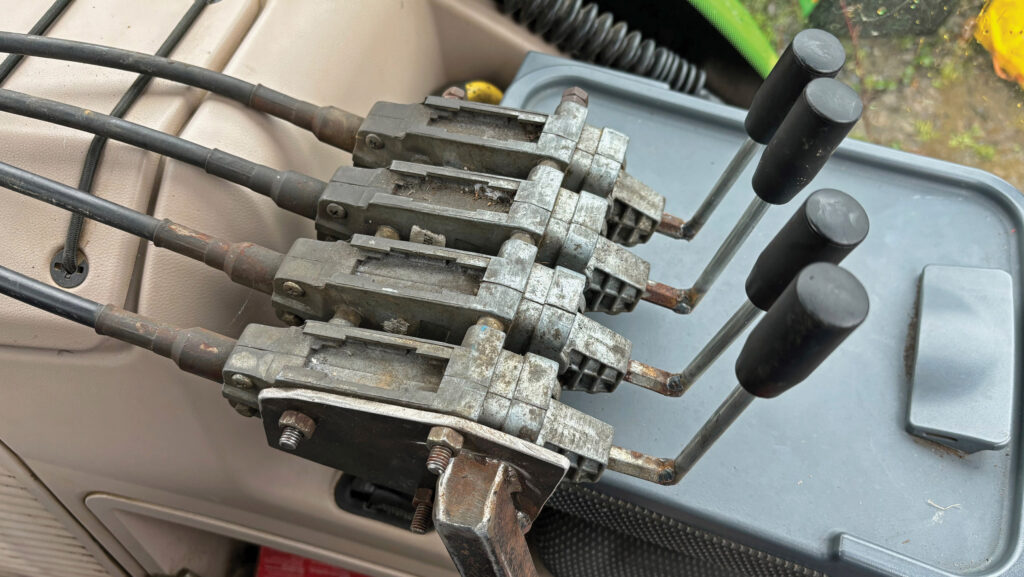

To operate these rams, Luke bought a four-way cable-operated valve block from Flow Fit for about £100.

This is controlled via a bank of levers from a Palfinger crane, which is mounted on an arm in the cab.

As the trimmer has five hydraulic functions – one too many for the valve block – he added an electric diverter valve.

This is operated via a floor-mounted pedal and toggles between the telescopic and slew rams, which are two of the lesser used functions.

Another considerable expense was £500 worth of flails and fittings. However, even with these pricey parts he managed to complete the entire build for about £3,500.

The project was finished earlier this year, having been put together during evenings and weekends over the past 24 months. It’s worked as intended and he says it’s got plenty of output for the modest number of hedges he needs to cut.

Next on his project list is a slurry dribble bar…