How Angus growers built cover crop broadcaster for just £4k

© MAG/Oliver Mark

© MAG/Oliver Mark Cover crop establishment doesn’t get any lower disturbance than the few tramline cleat marks left by Malcolm Pattullo’s New Holland T7.210.

Together with his father Ranald, they have developed a budget broadcaster to spread their home-brewed, seven-seed mix into a standing cereal crop across a 30m bout.

It’s a dirt-cheap and low-risk means of establishing not-for-profit greenery, with the outfit having cost £4,000 to assemble, the tractor supping just 1 litre/ha of diesel and daily outputs comfortably north of 60ha.

See also: Cover crop destruction machinery options compared

But it’s speed and timeliness that are the biggest benefits, with seed applied in early August – 12 days ahead of the combine and, ideally, just before a rain shower.

This gives the cover crop a two-week head start compared with post-harvest sowing.

And that’s all the more important in Angus where, as crop growth goes, two long and warm summer weeks are worth four in late September.

Farm facts

Farm 120ha owned, 100ha contract farmed

Cropping Wheat, barley, oats, potatoes, peas

Soil type Sandy loam

“For a couple of years we drilled the cover crops conventionally, but it just didn’t give them time to establish properly,” says Malcolm.

“Harvest doesn’t usually get started until mid-August and often rolls well into September, when soil temperatures are beginning to drop and the days are getting shorter.”

That tardiness forced a rethink, which started with a 24m Kuhn Aerojet – bought for £1,500 – to broadcast the mix into a standing crop.

This allowed one man to cover big acres at a quiet time of year, gave the cover more time to grow, and didn’t affect the autumn drilling campaign.

© MAG/Oliver Mark

“Those few weeks in August make a massive difference to establishment,” says Malcolm. “As we’ve no shortage of moisture here in Scotland, it can often be at cutterbar height by the time we combine the cereals.

“But we have to be careful. Spreading the seed too early causes the plants to grow leggy as they battle the crop for light, so we want them to germinate while the cereals are still in the field, then do most of their growing afterwards.”

Throwing the seed into a standing crop also means it ends up underneath the chopped straw, which can then be left undisturbed on the surface.

As a result, it doesn’t rob the soil of nitrogen as is decomposes, offers some protection from heavy rainfall over winter, and avoids the challenge of sowing in trashy conditions – and the inevitable hair-pinning around drill coulters that goes with it.

© MAG/Oliver Mark

Home build

However, after failing to successfully modify the Aerojet to match their tramlines, and with its broadcasting accuracy sub-par, they scrapped it and designed their own.

“Because of the mixture of seed sizes, spinning them on with a conventional fertiliser spreader was too inaccurate,” says Ranald.

“The small, light seeds wouldn’t throw as far as the heavy ones, particularly in a tall crop, and they sometimes shattered from the impact of the veins, so we needed a pneumatic machine.”

The starting point for their applicator was a 1,900-litre Kongskilde front hopper already on the farm for applying fertiliser when drilling and potato planting.

This was mounted on a rear box-section frame via a second three-point linkage, allowing it to be quickly removed when required for other jobs.

As well as whipping the press wheels off its undercarriage, the Pattullos also had to alter the ground-driven metering wheel.

When used for broadcasting, this is removed and replaced with chain and sprocket assembly linked to an old wheelbarrow wheel. A hydraulic ram pushes it against the tractor’s back wheel to give a true forward speed. Handily, it also reverses the drive to account for the hopper being rear mounted.

The rest of the tank is unchanged, with the same four metering units at its base running the standard fertiliser rollers – albeit with the rate shut right down.

“As we’re covering a big width at a reasonable speed, the original metering rollers worked fine. We just turn the hydraulic flow to the fan up slightly compared with fertiliser spreading,” says Malcolm.

Boom extension

The twin-fold steel boom was stripped from a donor 24m Scorgie sprayer, and it was here that the lion’s share of fabrication work took place.

For starters, it needed extending by 3m on each side to match the 30m tramlines and, as it’s welded to the main frame with no scope for lifting and lowering, variable geometry – which it didn’t have – was essential.

With that in mind, the Pattullos decided it would be easiest to add the extensions where each boom wing meets the central section.

“We were butchering the pivot points anyway, so it made sense to do all the work in those places.

“Plus, we didn’t want to extend the boom tips because the extra length would cause them to foul on the hopper when folded.”

The main metalwork involved removing the fixed pivots and replacing the top hinge with a hydraulic ram, thus giving pitch adjustment on both sides.

Doing so also added a couple of inches to each side of the rear section, allowing the wings to fold comfortably down the side of the tractor.

Smooth-walled, 63mm-bore plastic pipes – similar to those on the original Kuhn Aerojet – were fitted to carry seed from the flexible pipes aft of the metering unit to the four distribution heads.

These, too, were designed in-house, albeit with plenty of inspiration from the farm’s Lemken Solitair.

Like the drill, they feature vertical steel pipes with chamfered rings welded inside to produce a corrugation effect that forces air through the middle.

This ensures the seeds collide with the cone at the top, causing them to ping outwards and into the eight 25mm-wide distribution pipes that lead to the spreader plates.

The spreaders are set at 93cm spacings, with each one comfortably throwing the seed 50cm left and right – from a height of about 2m – to give a decent overlap.

© MAG/Oliver Mark

Spool-hungry hydraulics

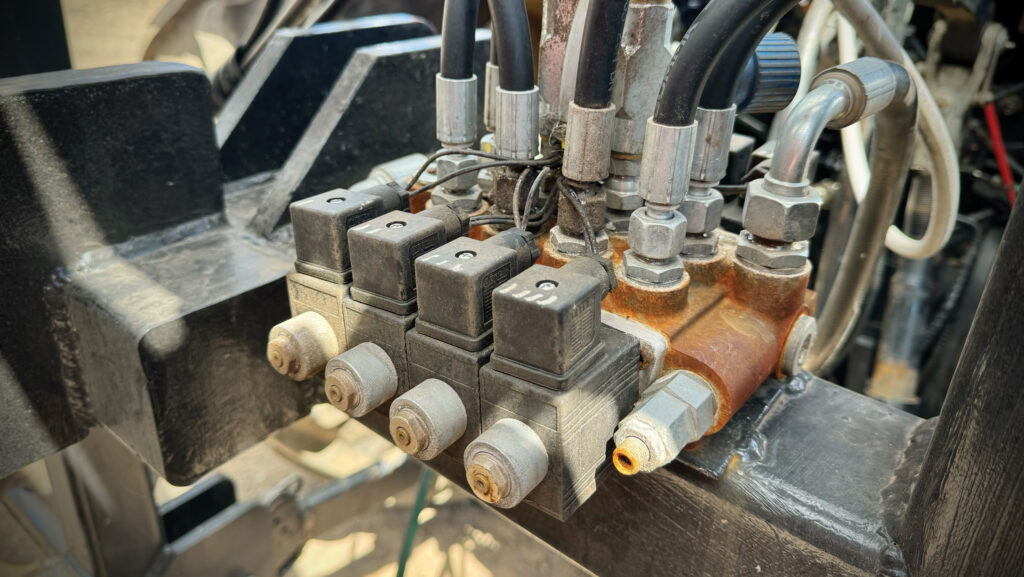

With a hydraulic ram added to the metering wheel and another two for the variable geometry boom functions, plus the existing pair for folding and another connection required to run the fan, it left the New Holland T7 chronically short of rear spools.

To solve the problem, the Pattullos invested almost £1,000 in a solenoid-activated hydraulic block and associated pipework.

This is plumbed into one double-acting valve set to constant pump, allowing Malcolm to work a simple electric switch box in the cab to fold/unfold the boom and tweak the pitch on either side.

That leaves enough spool capacity to run the fan and metering wheel ram as usual.

The finishing touch was to adapt a front linkage-mounted frame – already used for the farm’s Berthoud sprayer – to hold the booms in their transport position.

Here, they sit on old web rollers from a potato harvester, which allow them to move forwards and backwards slightly as they jiggle along the road.

© MAG/Oliver Mark

Improving the soil

After five years growing green cover ahead of spring-sown crops, which is grazed over winter by sheep from a neighbouring farm before being sprayed off and spring drilled, the Pattullos have noticed a marked improvement in soil condition and, in particular, organic matter.

This had diminished significantly in the years since the business ceased a straw for dung arrangement in 2010.

“We were still chopping all the cereal straw, but there was no manure going in and we were finding that, each year, we were just ploughing up the previous season’s trash,” says Ranald.

“And we could hardly see any worms. In a trial pit we might have found eight to 10, but now we’re finding 40 or more.”

That increase in organic matter has also improved water holding capacity on the sandy-loam soil, which in dry years helps reduce the amount of irrigation required on potato crops.

“We like to try and maintain the soil structure, and broadcasting is 100% zero tillage. The only downside is having to apply a higher seed rate than we would if we were drilling.

“We might put on four times more seed, but the establishment costs are minimal and we know it will grow well at the right time of year – there’s no point having 100% germination in November.”