Advertiser content

Why things are changing for liver fluke

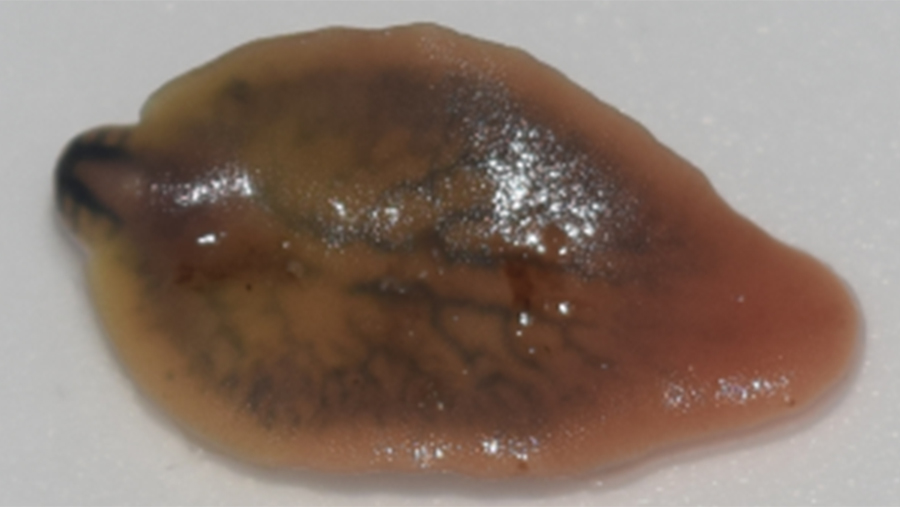

Liver fluke – a parasitic flatworm that lives in the liver systems of grazing livestock – has the combination of being both difficult to spot in animals and difficult to treat.

This fatally successful pathogen may have been around for a long time, but the message from one of the UK’s leading experts, Dr Philip Skuce*, is that farmers shouldn’t rely on following old methods to control it.

What are the best ways to spot liver fluke?

One of the classic signs of liver fluke in livestock is anaemia. Fluke is a blood-feeding parasite, so you’re looking for white in the eyes and gums.

Like with so many other diseases, weight loss and what we call “ill thrift” – animals hanging back, not acting right – are other signs, but you’ll need a more definitive test to establish that fluke is the cause.

Evidence of fluke can be picked up at the abattoir and a post-mortem, and while it will sadly be too late for the animal in question, it may still be possible to help the rest of the herd.

However, by far the most effective means of spotting fluke is through diagnostic testing.

Diagnostic fluke testing can not only tell you if your animals are infected, but also when and even where they were infected.

If you know where your animals are picking up fluke, you’ll be able to manage the grazing better and reduce the risk.

There’s also the importance of testing when it comes to treatment choices: different fluke treatments are designed to target the fluke at different stages of its life, and so it’s important to know what stage of fluke your animal has if you want the treatment to be effective.

What are the liver fluke testing options?

The earliest indication of fluke is found through a blood test. The best thing about this route is that the antibodies to the infection will show on a test within two weeks, so it’s a very early indication – particularly for young animals that haven’t seen fluke before.

There are also faecal tests. The faecal egg count is what we’re focused on here as the fluke are shedding eggs that get out in the faeces.

It’s a simple lab test, but the fluke only start laying eggs after they’re about 10 weeks old.

So, faecal egg counts only really detect the presence of adult parasites – you’ve got 10 weeks of potential infection that you can’t see with this route.

More recently, a test – called the coproantigen test – came out that can pick up a fluke secretion in faeces.

The coproantigen test is more sensitive than the egg count and it picks up infection a few weeks earlier, so it’s very useful.

However, it’s relatively expensive and only works well on individual animals, whereas the egg count can be done on groups.

Is there a problem with the treatment of liver fluke?

Improvements can often be made to the choice of product used and the timing of treatment given.

I think there’s an assumption that you use certain products at certain times of the year and every year is the same. But that’s not true.

The fluke’s lifecycle is dictated to a large extent by the weather – specifically the rainfall and temperature and how that affects the snails and the infectious stages.

But more recently we’ve seen fluke appear months later than we’d expect due to significant changes in UK weather patterns, with a series of dry springs and hot dry summers across most of the country.

Fluke treatment needs to be precise, and if we apply the approach that was used five years ago to next year, for example, it could be out by months.

At the moment, many farmers will blanket treat at certain times of year, which is not only less effective now but it is also causing treatment overuse, which itself leads to resistance problems to the few precious flukicides we have available.

Farmers will recall 2012-13 being a disaster for fluke – accounting for about a third of all livestock deaths in Scotland and many across most of England and Wales – at least some of the problems we saw were caused by resistant fluke populations.

Does there need to be a change in how we view liver fluke?

We’ve been guilty at times of using a one-size-fits-all approach with fluke and hoping that works out. But fluke is a very local parasite that evolves like any other pathogen.

We see big differences in the success of fluke in different regions of the UK, typically favouring the wetter west of the country, and believe it or not, big differences between neighbouring farms.

Yes, you and your neighbour may have the same weather, but you may also have very different ground conditions, soil pH etc, which are very important factors.

Ultimately, the treatment and management of fluke needs to become much more bespoke and farm specific.

I always say that you can ‘never say never with fluke’. You’re never going to eradicate it, it cycles through wildlife hosts like deer and rabbits as well, and it will exploit any opportunity it gets.

Our weather is becoming more unpredictable so another year as bad as 2012-13 remains a possibility.

What are your key takeaways for farmers dealing with liver fluke?

It’s all about doing the basics that bit better: carry out some diagnostic testing, timing your treatments, don’t treat if you don’t need to, manage your mud snail habitat more closely, and above all, understand fluke and what it thrives in.

And if you want to keep up-to-date with all things liver fluke, organisations such as SCOPS, COWS and Moredun are making lots of very important information easily accessible.

I’d also highly recommend looking at the very newly published AHDB Fluke Guide – it’s hot off the press!

*Dr Philip Skuce is not affiliated with Norbrook nor does he specifically endorse Norbrook’s pharmaceutical products.

Provided by

Norbrook is one of the largest, family owned, veterinary pharmaceutical companies in the world, dedicated to enhancing the health of farm animals.