Two city farms bridging the gap between city and countryside

Sheep at Mudchute with the towers of Canary Wharf © MAG/Judith Tooth

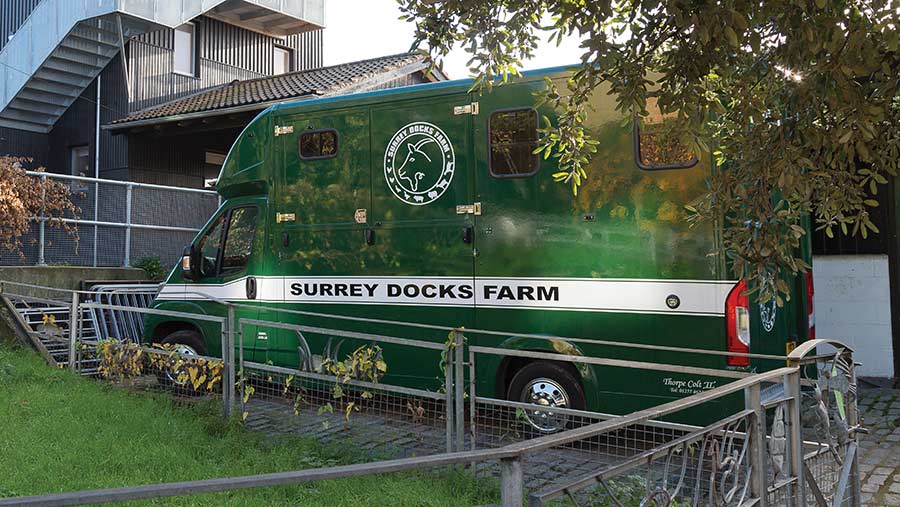

Sheep at Mudchute with the towers of Canary Wharf © MAG/Judith Tooth With less than 1ha (2.2 acres) to play with, space is at a premium at Surrey Docks Farm.

Not all London’s 12 city farms are as small (though some are even smaller) but they all go to great lengths to bring farming to their local communities, despite a host of challenges.

Surrey Docks Farm was set up in 1975 and has been at its present site, a former lorry park alongside the Thames, since 1985.

See also: Farmers showcase best of British food at Lord Mayor’s Show

Farm facts: Surrey Docks Farm, Rotherhithe

- 0.9ha

- Two Angus-cross bullocks

- 10 breeding ewes: Oxford Downs and commercial cross-breeds

- 10 nanny goats

- One Berkshire sow and one Middle White boar

- Chickens, ducks and geese

- Two donkeys and a miniature Shetland pony

- Beehives

- Apple orchard

- Vegetable plots

“As a city person, I have so much love for this farm as I know what it can give,” says livestock manager Claire Elson, who has worked there for more than 20 years.

She grew up in Peckham, visited the farm when she was in primary school and went on to study animal management at Sparsholt College in Hampshire.

“My parents took me out to the countryside, but lots [of children] don’t get that opportunity,” she adds.

Lack of space means feed must be bought in small quantities © MAG/Judith Tooth

The farm’s 10 staff cover farming, youth and education work, as well as projects for people with learning difficulties.

Two full-time apprenticeships (in livestock and gardening) are offered, as well as weekly work experience placements for young people – and there are more than 100 adult volunteers on the farm’s books.

“Some [volunteers] come because they love animals, some are referred by their doctor, some are between jobs, and some want a career in farming,” says Claire.

Claire Elson © MAG/Judith Tooth

Grazing management

With such a small site, grazing is limited, even in summer. Being on heavy clay, which quickly turns to sludge in wet weather, imposes further restrictions.

However, the cattle, sheep, donkeys and pony all have access to grass, albeit fields are watched carefully and closed off if conditions start to deteriorate.

Bought-in hard feed and hay, as well as straw for bedding, are relied on heavily.

Without the opportunity to shut fields for long periods, health challenges such as foot rot have to be tackled with regular foot dips, trimming, and treatment when necessary, says Claire.

“Because we know it’s a problem, we’re on high alert and carry out regular monitoring,” she says.

Access to services

As veterinary practices in central London deal only with small animals, a vet from outside the capital has to be brought in.

This adds to farm costs, particularly once the Congestion Charge and Ultra Low Emission Zone charge have been passed on.

Restrictions prohibiting larger vehicles using the nearby Rotherhithe Tunnel result in some longer journeys to the farm, adding further cost.

Not everyone is willing to deliver to central London, and lack of storage space demands regular deliveries of relatively small quantities from those who will.

“It’s like playing Tetris to get the hay and straw in,” says Claire.

© MAG/Judith Tooth

Similarly, there is no local abattoir – although this is a challenge not unique to London – so stock are taken to C Humphreys & Sons near Chelmsford, Essex, in the farm’s vehicle, towing a trailer borrowed from another city farm.

Carcasses are butchered by Brian Wilson at Hockley, near Southend.

Manure management

A small-scale biodigester is used to speed up manure and bedding decomposition.

This reduces pressure on space for storage and helps minimise waste exported by the farm.

The biodigester is stored in a large “inner tube” in a polytunnel and is maintained by students from University College London.

The resulting biofertiliser is pumped back to the muck heap to help it rot more quickly.

Once well-rotted, it is bagged into 1t sacks and supplied to local allotments and community gardens.

The gas produced by the biodigester is used to boil the kettle for the farm’s volunteers to make hot drinks.

© MAG/Judith Tooth

Sources of income

Feed, bedding and veterinary costs now total £28,000 a year. The farm receives funding from the local authority towards staff wages, but raising enough money to cover other costs is a constant challenge for Claire and her team.

Entry to the farm (open every day) is free, but £1 bags of feed are sold to visitors for the animals.

A charge is made for small animal petting at weekends and bottle-feeding lambs in season. Visiting school groups and a mobile farm used to deliver educational talks bring in further income.

Meat and other farm produce are sold in the on-site shop. “We get questioned every day about what we do, and we’re very open.

“We get a lot of vegan visitors and a lot of meat eaters. I’m very much about having a conversation,” says Claire.

With so many young people being able to learn the basics of livestock husbandry, Claire is keen to develop greater links with the farming community to create more opportunities for city people to forge careers in the industry.

Mudchute Park and Farm

Farm facts: Mudchute Park and Farm, Isle of Dogs

- 13ha of grassland, woodland and wetland

- Oxford Down, Norfolk Horn, White-faced Woodland and Soay sheep

- Dexter cattle

- Middle White and Tamworth pigs

- Golden Guernsey and Bagot goats

- Aviaries and small animal enclosures

- Five full-time and three part-time staff

Tom Davis, farm manager at Mudchute Park and Farm on the Isle of Dogs, was 10 years old when he spent his first day volunteering at a city farm.

He returned home to tell his parents he wanted to be a farmer, and has never looked back.

Tom Davis © MAG/Judith Tooth

“One of the best things about city farming is that we bridge the gap between farm and countryside,” he says.

“For some city people, it’s the only farming they see. I think we’re undervalued as a resource and underused in what we can do for the industry.”

Mudchute, a stone’s throw from Canary Wharf, is London’s only Rare Breeds Survival Trust approved conservation centre.

Since Covid and the cost-of-living crisis, the number of daily visitors has risen to more than 1,000.

In addition, school bookings bring 16,000 children to the farm each year.

And an after-school club runs five days a week, as well as a holiday club and a young farmers’ club, where children can help with farm tasks.

Challenges

Unlike Surrey Docks Farm, Mudchute (set up in 1977) is an open site. This means livestock can be accessed day and night, which brings potential issues, says Tom.

His focus in recent years, therefore, has been on encouraging the local community to have a sense of farm ownership, so they want to protect it.

Efforts are ongoing to educate people not to feed the livestock and to keep their dogs out of the enclosed grazing areas.

Having lost two cows to neospora, Tom has decided to buy in calves, rather than continue breeding Dexters.

© MAG/Judith Tooth

Although grazing is more plentiful at Mudchute, bought-in feed remains an important part of animal rations.

Options are limited, says Tom, because only a couple of merchants supply the city farms, and having to buy in bags always incurs a markup in price.

Non-bagged feed such as fodder beet would be impossible to access, he adds.