Thermal imaging cuts antibiotics use on Northants beef farm

© Hayley Parrott

© Hayley Parrott Livestock manager George Coles thinks thermal imaging is set to become a must-have for all farmers and could help reduce antibiotics use by enabling rapid disease detection and treatment.

Mr Coles has reduced antibiotics use across all the stock he owns and manages to nearly zero and knocked out the use of critically important antibiotics altogether, tackling most lameness with anti-inflammatories.

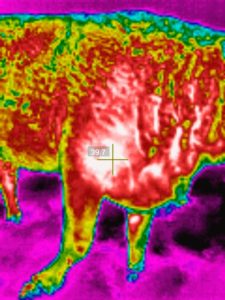

A thermal imaging camera, also sometimes called an infrared camera, detects the different temperatures of a subject and converts the data into an image.

Mr Coles began using the technology on his own beef cattle after picking up a camera from the equine section at an agricultural show.

“Straight away you could find that if you had a lame cow, you could see where the hotspots were,” says Mr Coles.

“The hotspots were often higher up in the leg rather than the foot, so you could treat it with anti-inflammatories, not antibiotics.”

See more: Sector-specific antibiotic reduction targets and what they mean for farmers

He says one of the beauties of the technology is the ease of monitoring after any treatment.

“Before thermal imaging, my treatment for anything limping was to give them antibiotics and anti-inflammatories and you’ve covered them.

George Coles

“Since I’ve been doing this, the only animals that have had antibiotics are those that have had a case of foul of the foot.”

Diagnosis from a distance

George Coles fact file

- Livestock manager at Owen Farms, Westbury

- Runs commercial suckler herd, calving 120 cows

- Managing a small red Aberdeen Angus herd

- Owns a small pedigree Simmental herd

The technology allows a non-invasive diagnosis, without requiring any contact, which can make it less stressful for animals and stockmen.

The closer you can get to the subject, the clearer the image gets, but it does mean you can make an assessment from a distance and only get the animal into a pen or handling area if the image suggests it is necessary.

Upon realising how valuable the technology could be to the farming industry, Mr Coles contacted suppliers and became the sole distributor to the agricultural industry for one of the manufacturers. This is when he set up his company, Miracle Tech, which officially launched in December and was runner-up for the Royal Dairy Innovation Award at the Dairy-Tech event.

Working with universities, vets, abattoirs, foot-trimmers and other technology companies, Mr Coles is exploring the possible future applications and uses of thermal imaging in agriculture.

Thermal imaging equipment

Use as a management tool

As well as diagnosing health issues, he believes thermal imaging can be useful for general stock management, as well as having potential in the mechanical and arable sectors in the future, looking at heat in machinery or assessing moisture levels in crops.

He has also used the technology to detect which cow will be calving next within the herd he manages.

The thermal imaging camera shows a rugby ball-shaped hot area from the tail down into the udder and when that heat zone is apparent, Mr Coles says the cow is likely to calve within three hours. This is useful for him as he lives off farm.

The technology can also be fitted to CCTV cameras in buildings, to help monitoring from a distance. Mr Coles is also looking at its use for picking up bulling heats.

“I want to try to get a real-time temperature, showing a real-time heat, so I can know the optimum time for AI,” says Mr Coles, who uses AI across the bulk of his sucklers and conducts AI for other farms too.

Having begun the research in the beef sector, he is now looking at its possible applications in the dairy industry, where mastitis and lameness may be two of the key health uses.

Thermal imaging benefits

- Alerts stockman to potential problem or need for action before it can be seen

- Reduces antibiotics use – saving costs and reducing resistance risk

- Avoids having to wait for withdrawal periods if drugs are avoided

- Non-contact – avoids getting animal in unless necessary

- Improved health and safety – it works from 1-2m distance

- Easy monitoring after diagnosis and/or treatment

Thermal imaging of the cow’s shoulder

Results on the farm

Mixed farmer Tom Herbert contacted George when he had a cow showing lameness, but couldn’t see an obvious cause.

“We suspected she had hurt her shoulder or foot. We hadn’t spoken to the vet prior and we are trying to reduce antibiotic use, so we thought we would give [thermal imaging] a shot,” said Mr Herbert.

“It showed a lot of heat in the shoulder so we came to the conclusion that anti-inflammatories were the best treatment.”

He said that he would rather take a different approach to treatment where possible, rather than “hitting and hoping” with antibiotics.

“Any antibiotics we can save is obviously doing to help everybody in the long run.”

Mr Herbert hasn’t bought his own camera because he doesn’t think he would have enough use for it with his 50 suckler cows, but believes it has great potential for the bigger beef herds and dairy units.

“I think it could be as good a management tool as EID,” he said.

Tom Herbert

Use in the abattoir

Meat processor Dawn Meats has also been trialling the technology in factories, to see if there is a correlation between any pre-slaughter stress and meat quality.

The science

The science of meat quality is a huge topic, but in its simplest form, muscles contain glycogen and if there is not enough glycogen in the muscles at the time of slaughter, insufficient lactic acid will be produced and the pH of meat will be high. High-pH meat can be darker and tougher.

Stress in an animal can cause low glycogen levels in muscles, meaning stressed animals are more likely to give poor-quality meat.

The trial

Anything with a high pH is unacceptable to many customers, according to Sarah Haire, agriculture strategy manager at Dawn Meats Group.

The company is using the technology to look for indicators of stress in animals in the lairage and then see if the meat on that carcass is poorer quality (darker cutting immediately after slaughter).

“The level of dark cutters is relatively low in our factories – our process is designed for minimal stress and we do as much as possible in terms of design, handling and training. But this is us trying to micromanage individual animals to see if we can detect stress, then manage that carcass better so we can maximise its potential,” Mrs Haire says.

“It’s too early for results – it’s still early days and there’s a lot to learn from it, but the opportunity is exciting.”