Sheep farmer beats foot-rot with vaccination and early treatment

Taking a tough stance on tackling lameness has been the only way West Sussex farmer Ryan Haydon has been able to almost eradicate foot-rot in his flock.

Eight years ago, Mr Haydon, who runs 500 Beulah Speckled Face ewes on the South Downs, had a lameness incidence of 5-10%.

“It was a totally unacceptable level,” admits Mr Haydon. “We had a number of chronic cases in the ewes and scald was a problem in the lambs. We had a stab at footbathing and vaccination but that didn’t seem to work to any great effect.”

It was at that point Mr Haydon decided to try a strict regime of culling chronic cases and setting in place a rigorous vaccination and treatment policy.

Culling

“We had no other option than to embark on a strict regime of culling out chronic disease, marking those individuals and culling them out.”

Identifying and treating clinical cases of foot-rot early was critical in its control. If Mr Haydon saw a lame animal he would treat it appropriately, mark it and then ear-tag for before culling.

“If a ewe wasn’t 100% sound then we would cull,” he says. In reality, Mr Haydon thinks he probably eliminated 3-4% of his flock because of the disease.

“We were brutal in culling the chronic cases for the first two years, but after this time we really did see a dramatic improvement.”

Vaccination

Vaccination was something Mr Haydon then introduced as a preventative measure alongside the rigorous culling and treatment.

“We initially started on twice-yearly vaccination for the ewes, rams and any lambs kept on until the autumn. We vaccinated for foot-rot in December and post-shearing. The reason for this was purely management, as post-shearing the vaccine we use can create a localised reaction site.”

It wasn’t until year three that Mr Haydon was able to drop the number of vaccinations to once a year. All of the breeding flock including rams now receive a booster in December.

However, any replacements are given two doses of the vaccine before dropping to one a year with the remainder of the flock.

Although Mr Haydon has almost eradicated foot-rot on his farm, he still continues to vaccinate.

“Although we now have levels to less than 1% we can’t forget where we came from. We still operate a rigorous treatment regime and, if we get any cases, we still take out offenders.”

Rapid and appropriate treatment

Lameness expert Laura Green of Warwick University stresses the importance of rapid and appropriate treatment.

“The sooner you treat the quicker you will get under control and prevent spread of infection to other sheep. By doing rapid and appropriate treatment of foot-rot there is no reason why levels of 2% and under can’t easily be achieved.”

When foot-rot is detected, Prof Green says treatment should be in the form of a long-acting antibiotic used at the right dose, along with a topical spray used on all four feet.

“I also wouldn’t recommend trimming feet at this stage as this will delay healing. Animals infected should also be marked so repeat offenders are easy to identify,” she says.

“Rigorous and rapid treatment and culling out repeat offenders will drive down levels within months – if you don’t treat you will always have lame sheep. Getting on top of foot-rot will mean you will also get on top of scald, as scald tends to come from a foot-rot epidemic in ewes.”

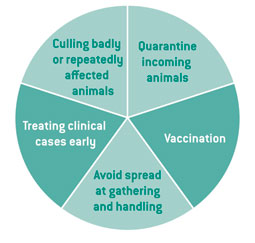

Expert comment on the five-point plan

Ruth Clements, FAI Farms

The development of the five-point plan came from frustration with our own sheep at FAI Farms. When we first started looking for a practical method of controlling lameness, we had an incidence of 18.5% in our flock of 800 ewes, which was totally unacceptable.

At the time we were starting our work on lameness, we met West Sussex farmer, Ryan Haydon who had been doing all the things in the five-point plan.

So together with Mr Haydon we worked the five different areas into a five-step protocol.

It seemed like a good, common-sense approach. The plan was developed over a three-year period and trialled on several commercial farms – all with success.

It’s not a perfect world, so the plan incorporates the evidence of science alongside what works practically.

The five-point plan is about looking at the whole picture.

The five-point plan is about looking at the whole picture.

And the most important step for any farmer looking at tackling lameness is to adopt a mindset change and accept that it is achievable and then throw everything at it.

If you go at it half-heartedly you will not achieve success.

We saw positive changes within the first year and if you can stick to it, you to can expect to see positive results by the end of year one. After 18 months we had achieved lameness levels of less than 1%.

Forced culling was something we were very strict on. In the first year we culled 4.2% on top of other sheep that were culled for the usual reasons, such as mastitis.

We also reduced spread at handling and gathering areas by moving over to a mobile handling system.

Vaccination was something we introduced to get on top of the problem. It helps give you a leg up to allow the other control measures a chance of working.

We vaccinate the whole breeding flock, including rams, biannually, and are flexible with timing and frequency of vaccination, fitting it in when it suits us.

Lameness really is an issue we, as an industry, need to get on top of. If you ever catch yourself saying a sheep is “only a bit lame” then there is a problem.

Lameness to any degree is causing pain and we definitely should not be waiting until an animal is holding its limb up before doing something about it.

FAI Farms in Oxfordshire was originally set up by farmers in 1998 in recognition of the existence of commercially robust alternative systems that significantly raise animal welfare standards, tackle environmental concerns and address issues of human health. FAI is committed to developing actionable solutions to animal health problems.