How a farmer is benefiting from installing slurry separator

© MAG/Rhian Price

© MAG/Rhian Price Investing in a slurry separator has reduced labour requirements on a Shropshire dairy unit.

Tim Dale installed the separator last autumn to alleviate the need to pump slurry into a second pit.

Slurry produced by the 360 milking cows plus followers at Little Shrawardine Farm, near Shrewsbury, is scraped into an open lagoon with a concrete bottom.

See also: 8 new rules for water and what they mean for farmers

A second, earth-lined pit was added 10-15 years ago to increase capacity and meet nitrate vulnerable zone equirements. This second pit acts as an overflow facility, but thick slurry was clogging up the pipe.

Farm facts

Little Shrawardine Farm, near Shrewsbury, Shropshire

- Milking 360 Holsteins

- Calving year-round, with heifer replacements calved in a two-month block in July and August

- Using British Blue and Angus semen to produce beef animals

- Supplying Arla

- Producing 11,000 litres on twice-a-day milking

- Farming 202ha (500 acres) with 40ha (100 acres) rented

- Growing 40ha (110 acres) of maize, 36ha (90 acres) of wheat, 36ha (90 acres) of temporary grass and the remainder permanent pasture.

“The slurry wouldn’t go down the pipe to the second pit, so we spent lots of time pumping,” explains Mr Dale, who farms with his parents, Sheila and Derwas, and wife, Laura.

The headache for most dairy farmers bedding cows on sand is finding a mechanical solution that can withstand the abrasive wear.

Mr Dale heard about a Sperrin Optiflow slurry separator from Stamford Agricultural Services being used by a 2,000-cow dairy farm that also bedded cows on sand, and visited the farm to see it in action.

“I thought, if it works for them it would work for [a smaller unit] like ours,” he says.

How it works

The separator was a significant investment at about £50,000, including groundworks.

It works by separating the liquid from the solid fraction, pumping slurry out of the pit and up to the machine where a roller-press is used to squeeze out the liquid like an old-fashioned clothes mangle.

This leaves a solid, friable fraction which is about 25-30% dry matter and has helped increase storage by about 8%. This is stacked on the floor at the foot of the machine and the liquid fraction then gets released back into the lagoon.

Because the slurry in the first lagoon is thinner, it now flows freely into the overflow pit with no intervention required.

Technically, when you install a separator, you would have a moderate size reception pit that would be emptied through the separator.

But a lot of effort would have been required to convert the existing setup, explains Mr Dale.

“So, we let the sand settle out in the first pit by gravity and then we use the separator to encourage overflow into the second pit.”

As the first reception pit is concrete-lined, this also makes it easier to clean out, he adds.

The separator is in operation for about five months of the year, from November to March.

“We will empty the pit before the closed period starts on 15 October. It will start to fill up within four-to-six weeks and we will use the separator from the middle of November all the way through to when we are allowed to spread the following March, conditions permitting,” explains Mr Dale.

Low-yielding cows at the farm are grazed during the summer months, which further alleviates pressure on storage capacity and means the second pit is surplus to requirement until the winter.

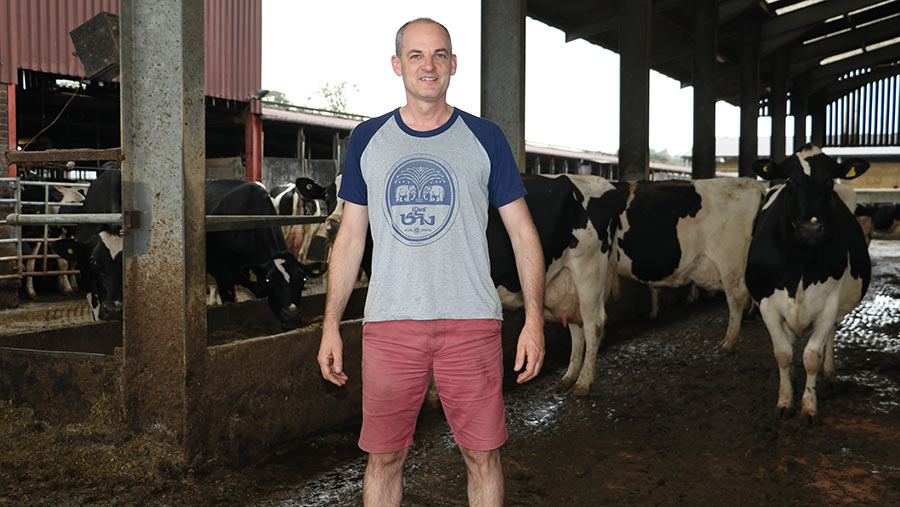

Tim Dale © MAG/Rhian Price

Spreading

One of the benefits is that Mr Dale now has two products – a solid, friable fraction and a liquid portion – both of which can be targeted more effectively according to crop need.

The solid fraction is spread on the maize before planting in the spring, using a hired, rear-discharge spreader.

“Because it’s very fine material it spreads easily and you can get it onto grassland without it contaminating silage, so this time we used it on our first cut silage,” explains Mr Dale.

Meanwhile, the liquid fraction is spread on grassland between cuts and after grazing, using an umbilical tanker.

Previously, Mr Dale used a splash plate, but he invested in a trailing shoe tanker in 2016.

The tanker has been modified with linkage to support a tined cultivator so that the ground can be cultivated at the same time, and slurry is injected directly into the cultivated ground behind.

“If we are growing maize after maize or drilling a crop into wheat stubble, we don’t have to worry about cultivating after the slurry has been spread. It doesn’t smell so much and avoids upsetting the locals.”

This makes up a good-quality, mostly homegrown diet for the cows, with high-yielding milkers fed 60% maize and 40% grass-silage, alongside caustic wheat, nutritionally improved straw (NIS), rapemeal and Trafford syrup.

Low-yielding cows are fed grass-silage and concentrate in the parlour.

“The NIS is a good match for the caustic wheat. It’s the best balance I have found. I could feed more beet pulp for fibre but then we would have to sell the wheat. This makes the best use of what we grow on farm.”

Benefits

The improvement in storage will help Mr Dale comply with the new Farming Rules for Water, which permit spreading only if there is a crop need.

He says it will also help the farm meet new phosphate rules, which will prevent farmers from spreading slurry if soils are over index three for phosphate.

“By separating the fraction, the solid is P and K and the liquid is nitrogen, so it makes it easier to target which fields need it.”

But Mr Dale says to meet these new rules, coming into force next spring, farmers will need to make considerable investment on-farm, and he says the government must come up with funding to support this.

Savings and benefits

Many farmers invest in slurry separators thinking it will increase storage capacity by much more than it does, explains Dave Turner from Stamford Agricultural Services.

“Slurry to start with is 10-12% dry matter, so if it takes it to 25-30% dry matter you’re only going to get another 8% capacity. Buying extra storage [is therefore] not a reason to get a separator.”

Instead, Mr Turner says the biggest benefit is the fact you get two products – a liquid fraction high in nitrogen and ideal for spreading on grazing and silage ground to prevent leaf taint and a solid fraction high in p and k that is better suited for maize crops.

He says many farmers that are better able to utilise slurry in this way have been able to stop buying fertiliser, saving thousands.

“I think people are realising slurry is something to be used and isn’t just a waste product.”