Tips on ensuring poultry biosecurity measures are effective

© Tim Scrivener

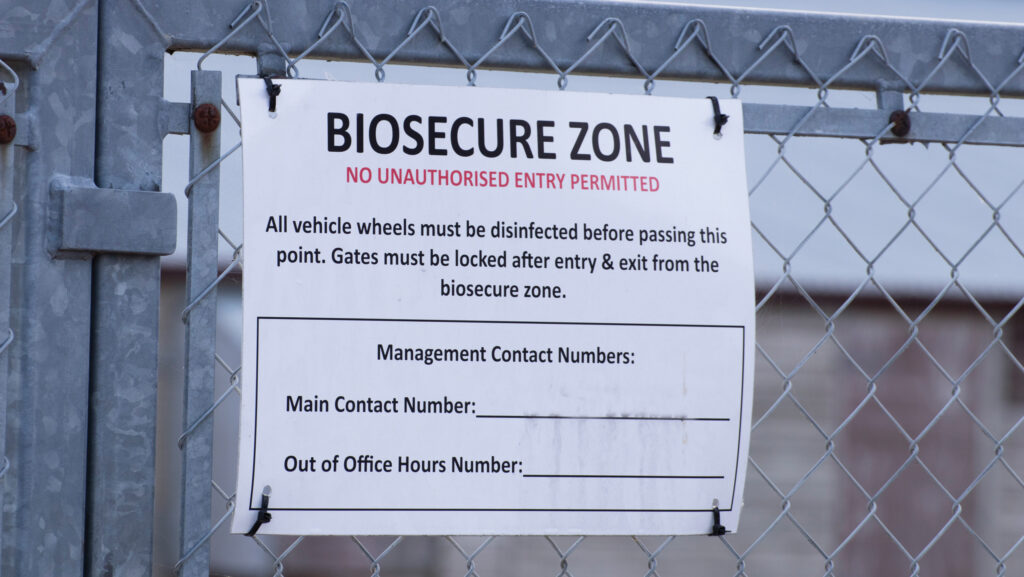

© Tim Scrivener The avian influenza virus always makes its way into a poultry house from the outside environment, so preventing that transmission will keep disease at bay.

While farms already have good biosecurity measures in place, a weakness on many is a failure to correctly implement these, making controls futile.

Former poultry farmer Paul Talling, a biosecurity adviser at Livetec Systems, says that a first step to making biosecurity controls effective is understanding why each measure is needed, and how it should work.

See also: Poultry housing order extended in the north of England

Paul Talling © Livetec Systems

He gives a step-over barrier as an example. “If you don’t know how to use and maintain it, you might as well not have it,” he suggests.

“By ticking the assurance scheme box for having a [step-over] barrier, there can be a tendency to think that alone will stop everything, but it won’t.”

After an outbreak of bird flu, an epidemiology report often gives indirect contact with a wild bird as the reason for the disease breakdown.

“It doesn’t really tell the flock owner anything apart from the likely source of infection, but the virus had to get onto the farm and into the shed,” Paul points out.

When he assesses a site, he can mostly work out how the virus got in.

“The disease doesn’t originate in the house, it always has to get in somehow [from the outside].

“Producers are getting good at netting all their vents so birds and vermin can’t get in, making sure they have proper perimeter fencing and barriers.”

But, he adds, if someone is walking into the shed from outside wearing the same boots, they are setting themselves up for a lot of problems.

1. Prevent any pooling of water

The avian influenza virus can live in water for months, therefore even a single puddle will risk transmission to poultry.

Paul says he frequently sees pools of dirty water on farms he visits following a bird flu outbreak.

He believes that, in many cases, these would have been the most likely source of the disease.

If a wild bird carrying the virus drinks from the puddle or paddles in it, there is every chance that the infection will transfer to the water.

“At some point, somebody will make a mistake and introduce that water into the house – they might, for instance, walk out through the back door of the shed to take a break outside, stand in a dirty puddle, and walk back in without going through the biosecurity barrier at the front,” he warns.

“In many ways, it is [human] behavioural change that is needed, but in that example, having something structural too – like a [staff] room where people can take a break – should be considered.”

Filling in all surfaces where water can collect is one of the most important ways transmission of the disease can be avoided.

“Ideally, concrete over any hollows, but at the very least fill them with stone to dry them out,” Paul advises.

Starling drinking from a puddle © Adobe Stock

2. Have robust vermin controls

Securing sheds against vermin must be a priority. If there are rats and mice around them, there is every chance that at some point one or more will gain entry.

A rat that has come into contact with infected water in a roof gutter will not disinfect its feet before it goes into the shed, Paul points out.

“It is a very, very hard task to completely prevent vermin from getting in, but it should be given the highest priority because if you have vermin activity, you have got potential for them to walk the virus into the shed,” he says.

“You have got to be really on top of vermin control – they must be kept away from poultry.”

3. Keep all bedding secure from birds, vermin and water

Many units that have experienced breakdowns during the current bird flu season are turkey and duck producers who are running systems that need to bed regularly.

This increases the frequency of people and machinery entering the shed.

“It is that increased frequency that makes the risk bigger,” says Paul.

“Bedding up is intrinsically dangerous. Very few broiler farms have gone down this time, and those have systems where the shed is entered just once or twice a day, and by only one person,” he points out.

As well as keeping vermin and birds out of sheds, there must be no opportunity for them to make contact with bedding in storage.

“You just can’t leave a bale of straw in a puddled wet area outside the shed before it is taken in – the risk is too great,” says Paul.

In addition, vehicles entering the building should be meticulously clean.

4. Use biosecurity barriers correctly

Even units with the best biosecurity barrier systems can fail to use them correctly. For example, quite often there will be a hut at the entrance where clothing can be changed.

“This is really good, but nine times out of 10 people will walk out of the same door that they walked in through.

“That means whatever they walked [onto the floor] on their footwear, they are taking straight back out again after changing. It makes the whole thing pointless,” says Paul.

In the case of step-over barriers, he favours bench barriers as it is easier to change footwear and clothing when sitting down.

Some farms have a double step-over barrier, but he says he quite often sees situations where the floor separating the two areas is dirty.

“If there is dirt on the floor between the step-overs, then that system is not working,” he explains.

The absence of a drain is often a principal reason for dirt being present, he adds.

“That comes down to shed design.

We have been into brand-new sheds where there is no drainage in those areas, so even with the best will in the world, the floor between the step-overs can’t be kept clean.”

© Tim Scrivener

5. Use digital platforms for biosecurity advice

With the risk from avian influenza ongoing, digital systems have been developed with biosecurity assessment tools that help producers manage that risk.

The Livestock Protect app from Livetec, for example, has transferred the assessment system from a physical visit by its biosecurity advisers to a digital format.

Paul says this opens up greater access to units they want to assess, if their own controls are suitably robust.

“Some of the recommendations within that part of the app are very specific to particular areas,” he says.

This allows farmers to question the effectiveness of their biosecurity and gives advice on what they can potentially do to improve if needed.

The app also has a free service that issues real-time alerts to smartphones on local disease risks.

These give farmers the opportunity to take swift action to safeguard their flocks if there is an outbreak locally.