Poultry production through the ages

A few years ago, Poultry World published The Triumph of Science. Written by the late Thomas E Whittle of the Scottish Agricultural College, it surveyed the history of 20th century poultry production. Philip Clarke revisits key events.

First half of the century – layers

The exact start date of “modern” poultry production is hard to pinpoint.

Before the First World War, keeping poultry was never much more than a cottage industry, providing meat and eggs for the kitchen table. But, post-1918, the sector became something of a “haven for ex- servicemen”.

“After the war, many ex-servicemen had no job to go to. Those who had an aptitude for it were encouraged to go into agriculture,” wrote Thomas Whittle. “They were offered special training courses and financial assistance, quite often in poultry production since the capital requirement was relatively small.”

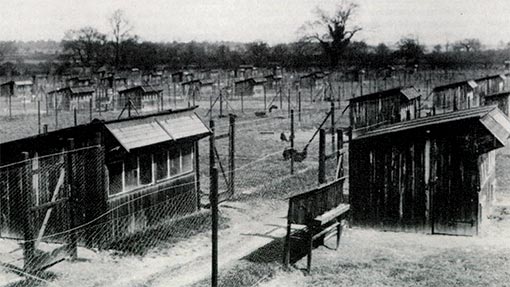

Many started out on County Council smallholdings, and 1,000 layer breeders were deemed sufficient to provide a living for a man, wife and child. Bird accommodation was invariably “self-build”, while feed was “home mix”. Daily “trap nesting” was the norm, with stock cockerels bought in annually from established breeders. Many would have had their own oil-heated incubators, including the Gloucester, the Glevum and the Hearson.

See also: Read all of Poultry World’s 140th anniversary articles

Later models, holding up to 6,000 eggs, used hot water heating systems. Chicks were brooded indoors for six weeks, then moved outside to a rearing range, with slatted night arks holding up to 40 pullets.

Cockerels were removed at 16 weeks and sold for table consumption – at least that was the common practice until the 1930s, when vent sexing was introduced from Japan, after which male chicks could be culled at day-old.

Laying trials

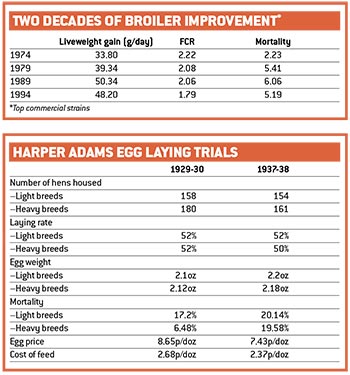

At about this time, a number of Utility Poultry Societies were set up, to help with egg marketing and technological improvement. This led to the introduction of numerous competitive laying trials, including ones at Harper Adams Agricultural College and the Lancashire International Laying trial.

Birds achieving more than 200 eggs over 48 weeks (336 days) were issued with a certified copper ring, and regular winners included the likes of Tom Barron, Joe Rainford and Jack Wrennal. “Given that these birds were essentially free range, without any artificial lighting or modern nutrition, these records are impressive,” wrote Mr Whittle.

But the emergence of a more commercial poultry sector, with over 60 million layers on UK farms in the 1930s, was not without its challenges. Disease was a growing threat, primarily in the form of coccidiosis and Fowl Paralysis – later known as Marek’s disease.

Marek’s disease was dealt with by culling infected breed stock and only breeding from second or third year birds.

With the onset of the Second World War the government prioritised using grain to feed people, rather than intensive livestock. As a result the poultry population plummeted.

Post-war period – layers

The development of the egg sector got back on track again in 1947, with the launch of the Accredited Breeding Scheme.

While feed rationing did not end until 1953, it was soon recognised that productivity needed to increase fast, and so two new grades of accredited stock were established by the Agriculture Ministry – “breeders grade” and “commercial grade”. Each had strict management and selection standards and, to make breeders grade, hens had to lay over 165 eggs of over 2oz in 48 weeks.

Progeny testing was also introduced, while all adult birds were blood tested for Salmonella pullorum, with any reactors slaughtered.

These measures led to the overall improvement of what were essentially pure breeds of layers (Leghorns, Rhode Island Reds and Sussex), until the emergence of hybrid strains in the 1960s.

Derationing

Feed derationing was key to growth for the layer sector. At this time, free range was still the norm, with birds kept in fold units, which could be moved daily to reduce disease.

But intensification was just around the corner, triggered in particular by work at Reading University’s Lane End Farm into the impact of lighting. Building on US research, the Reading team developed light-proof housing and lighting regimes designed to stimulate the onset of lay at 18 weeks.

The 1950s also saw the development of deep litter housing, with the birds kept in barns and the litter allowed to accumulate for three or four crops before clean out. Perches and droppings pits came later.

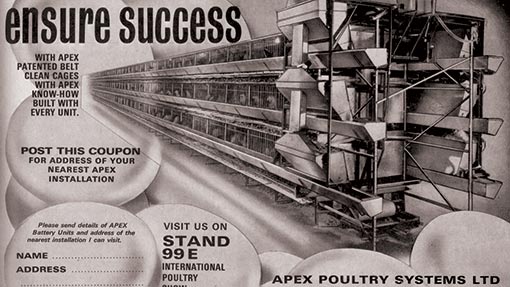

“But perhaps the greatest revolution in the 1950s and 1960s was the very rapid development of battery cages for layers,” wrote Mr Writtle.

The original cages were invented by a Major Frew of Somerset in the 1930s, using wood, wire, mash hoppers and jam jars for water. This was superseded by a more commercial design at Lancashire College of Agriculture, Preston, which attracted “many thousands of visitors”.

Cages evolved rapidly, to house four or five layers each, with up to six tiers. Systems were developed to clear away manure, ranging from tyre scrapers on ropes, to droppings boards and continuous rolls of paper.

Feeding was typically a dry mash, though a Daniel Marshall of Newbridge, Edinburgh, invented a “cafeteria” type system that travelled on rails and gave each bird about 10 minutes’ feeding time.

For many years water was supplied in troughs along the front of the cages, with a ball valve to keep levels constant. But these were replaced in the early 1960s with Ascot nipple drinkers, sometimes sited above the feed belts and allowed to drip on to the mash.

Hybrids

The other big development in the egg sector was the advent of hybrid strains of layer. Again, the pioneering work was done in the USA, but import restrictions due to Newcastle disease meant the UK was barred from accessing this stock.

Help was at hand, however, and Yorkshireman, Cyril Thornber, with his geneticist John Archibald, set about developing a British hybrid. The first White Leghorn cross was the 101, followed by a Black Leghorn cross 202. The most successful, however, was the Rhode Island Red/Light Sussex cross – the 404.

From the late 1950s to the mid-1970s it is reported that 250 million of these chicks were sold. They were followed by White Leghorn 505 and 606 strains – better suited to a cage environment.

Post war period – broilers

Up until the Second World War, meat birds were pretty much a by-product of the egg sector. Rhode Island Red/Light Sussex cross cockerels were tasty, but scraggy.

The greater demand was therefore for capons, castrated male birds that took on female characteristics – notably more breast meat. But the process of removing the testes, involving making two slits between the last two ribs and cutting them out, was tricky and eventually banned.

In the early 1950s, chemical caponisation was developed, involving inserting a female hormone pellet in the neck. This, too, was later banned.

But the end of feed rationing in 1953, and the arrival of more specialist broiler, or “grilling”, chicken from the USA in 1956, gave the poultrymeat sector the boost it needed.

These specialised meat birds actually grew out of a number of “Chicken of Tomorrow” contests, organised by a US supermarket between 1948-1951. This culminated in the development of the Vantress White Cornish – a cross between a White Indian Game male and a White Plymouth Rock female – which delivered excellent breast conformation and eating quality.

The import ban due to Newcastle disease kept such desirable birds out of the UK market, until such time as Scottish breeder Rupert Chalmers-Watson secured a special licence for grandparent stock in 1956.

With New Hampshire breeder Fred Nichols, he set up Chunky Chicks Ltd at Newbridge, near Edinburgh, overseeing further crosses that delivered better meat yield as well as hatchability.

A hatchery and a meat processing plant were then built in partnership with Daniel Marshall at Newbridge and the Chunky Chick meat bird was established in the UK market. (The breeding side later became Ross Breeders, the meat factory grew into the Marshall Food Group.)

Weight gain

In the early days, a 5,000-bird broiler house was pretty typical, turning out four crops a year. Records show that, in the 1960s, Chunky Chicks were reaching 2kg at 63 days, and were consuming 5kg of food to get there, (equivalent to an FCR of 2.5). That compares with a modern broiler today that can achieve that weight in half that time, with an FCR of 1.6-1.7.

In The Triumph of Science, Mr Whittle praises the work of the scientific community that transformed the broiler sector during the 1970s and 1980s, and turned a luxury food item into a household staple.

“Mortality in layers, broiler chickens and turkeys is a relatively minor production constraint, thanks to improved genetics, modern nutrition, environmental management and prophylactic drugs,” he wrote.

“It is characteristic of efficient, modern husbandry and management to control all aspects of the environment within fine limits – temperature, insulation, ventilation, light, humidity and sound – using the very latest electronic technology.

“All the sciences have played a part, not least poultry nutrition and the development of vaccines by our veterinary researchers.”