Advice on managing welfare issues in multi-tier layer systems

© Tim Scrivener

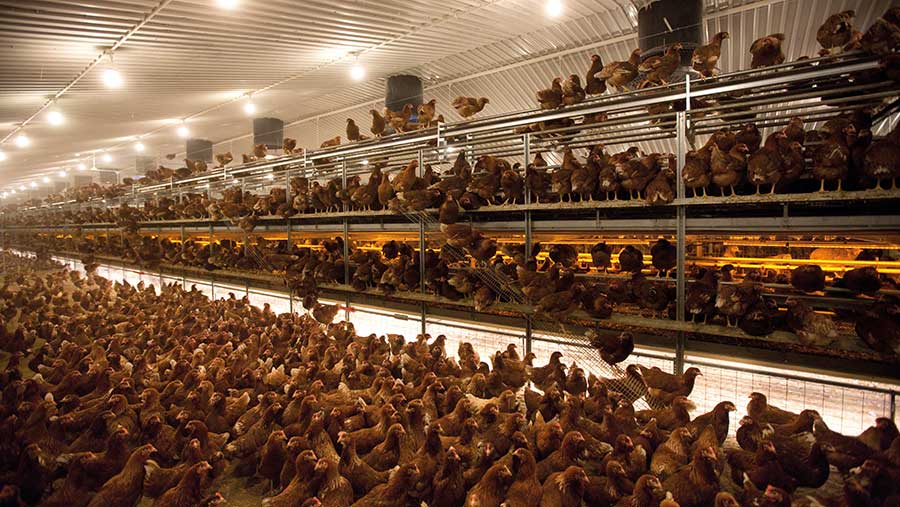

© Tim Scrivener Multi-tier laying hen systems are growing in popularity, allowing more birds to be kept in a given shed footprint. However, it is important to understand the additional welfare considerations of using these setups.

Vicky Sandilands, senior behaviour and welfare scientist at Scotland’s Rural College, carried out a research project comparing multi-tier and flat-deck systems and that also looked at the value enrichments could offer.

These are her main findings, which will be unveiled in full at the British Pig & Poultry Fair on 10-11 May.

See also: Expert tips to reduce poultry vet and medicine costs

What are the main differences?

Multi-tier systems are expensive to install. However, one of the benefits to producers is that they can put more birds in a multi-tier system compared to a flat-deck, but with the same shed footprint.

“Some farmers were adamant they were not going to use multi-tier as it was bad for the birds, but others were saying it’s good for them as they move through the space as they would do naturally if they were going up trees to roost,” says Dr Sandilands.

Dr Sandilands’ research didn’t show a significant difference between the two systems in terms of mortality, although it was slightly higher in the flat-deck system (7.5% in flat deck, compared with 4.8% in multi-tier at 70 weeks of age) across 42 flocks, visited between 69 and 90 weeks of age.

“A higher mortality rate and lower average egg production, due to less birds in the flat-deck system, makes a significant difference financially in favour of the multi-tier system.”

She found a £10.32 margin a bird over feed to 70 weeks in a flat-deck system versus £10.92 in a multi-tier one.

However, keelbone damage was much higher in the multi-tier system; keelbone deviation was found to be 48% compared to 28%.

“We know it’s more likely to occur where birds have the ability to move around a lot – like in multi-tier systems, where birds have to descend to a crowded floor,” says Dr Sandilands.

Average percentage of flocks with keelbone fractures and deviations |

||

|

Keelbone fractures |

Number of birds in sample group |

|

|

Flat deck |

28% |

690 |

|

Multi-tier |

48% |

460 |

|

Keelbone deviations |

Number of birds in sample group |

|

|

Flat-deck |

3.2% |

690 |

|

Multi-tier |

7.4% |

460 |

When descending, they are trying to land on a busy floor with other birds and furniture – which can be a source of injury as the keelbone dips or twists.

The percentage of flocks with keelbone fracture is almost double in a multi-tier system (7.4%) compared with a flat-deck (3.2%).

This is a real welfare concern, says Dr Sandilands. “The problem is, you can’t see it.”

So how do you reduce it? “One of the recommendations is to provide ramps, so birds can walk down between tiers – they can also help to break birds’ fall if they are knocked off.”

How enrichments can help

Dr Sandilands has also looked at whether various means of enriching the birds’ environment are effective. “Enrichment is an important consideration when it comes to bird welfare, with benefits such as reducing feather pecking.

“Some accreditation schemes also require one enrichment for every 1,000 birds. We were curious about the enrichments that free-range and organic producers were having to put in, were they really any good?”

She looked at four different enrichments, provided at a rate of one enrichment to 1,000 hens. In every 4,000-hen colony there were at least four enrichments of two different types, to comply with regulations.

The enrichments were: lucerne hay bales, pecking blocks, scattered feed and rope.

“Rope is a commonly used enrichment because it’s cheap. We wanted to mainly use enrichments that were already being used on farm because we felt it was more important to evaluate those than try something new.”

Key welfare findings

- Scratch mat design doesn’t make a difference to hen behaviour

- Ropes don’t generate much interest but they are the cheapest so may be worth offering alongside another enrichment

- Multi-tier systems have the greatest risk of keelbone fracture and deviation compared with flat-deck systems

The birds were observed within a 1m radius of the enrichment – this was classed as showing interest, whereas those further away were not.

The study showed that scattering feed did create a lot of interest.

“The feed was scattered twice a day at a rate of 1g a bird. We saw a peak of interest in the area where the feed was scattered as well as continuous interest in the area after the feed was depleted.

“Some regulations don’t class scattering feed as an enrichment because it isn’t continuously available – so we did have to get permission for the farms to use it in the study,” she adds.

While there was consistent interest in peck blocks and bales, there was least interest in ropes.

They are commonly used because they are cheap but they might as well not be there; there was no difference when comparing the 1m circle around the ropes with the area outside of the circle.

“That could be because the birds don’t find the ropes interesting or because they are just 30cm lengths looped over a rail – they aren’t very big compared to a bale or pecking block,” she says.

© Matt Cartney

Dr Sandilands also calculated the cost of providing enrichments for a flock of 16,000 hens housed for 80 weeks.

Including replacement of the enrichments when necessary, the bales cost £2,000, peck blocks £6,500 and pelleted feed £3,000, but ropes were £6.54.

So, financially, ropes are an attractive option.

“If you have to provide two different types of enrichment for every 1,000 hens, the ropes are cheap, so could be paired with another enrichment. You may not want to spend close to £9,000 when you can spend £2,000.

“That’s one of the realities – you have to balance it with what’s practical. If your accreditation stipulates two enrichments, perhaps consider offering ropes as one and peck blocks or bales as a second.”

Are scratch mats worthwhile?

Welfare legislation requires producers to provide litter, allowing pecking and scratching in enriched layer cages.

As a result, cage manufacturers offer a variety of different scratch mats of various sizes, shapes and materials.

The idea behind the scratch mats is to encourage pecking and scratching behaviour, as in the wild chickens would spend a lot of time foraging for food.

“I wanted to find out if it actually made a difference to the hens in terms of the time they spent there and proportion of time they spent showing foraging-type behaviours,” says Dr Sandilands.

In a commercial setting, producers dispense a small amount of feed onto the mats to encourage foraging, but as the mats aren’t very big, only two or three hens will fit on them at one time.

“The feed is quickly depleted, initial interest is lost and they may look to peck at something else – like each other, leading to feather pecking.”

Despite the different sizes and designs of scratch mats, there didn’t appear to be an optimal one and overall use was low.

However, Dr Sandilands acknowledged that commercial hens aren’t used to people standing and observing them, which may have affected their behaviour and trial results.

“For scratch mats to be effective I think feed needs to be dispensed onto them frequently.”

Predicted physical performance and financial margins over feed |

||

|

|

Flat-deck |

Multi-tier |

|

Egg yield per bird to 70 weeks (hen housed) |

283 |

286 |

|

Cumulative mortality to 70 weeks (%) |

5.6 |

4.8 |

|

Average second-quality eggs to 70 weeks (%) |

3.8 |

3.4 |

|

Average feed intake (g/bird/day) |

123.7 |

120 |

|

Margin per bird over feed to 70 weeks (£) |

10.32 |

10.92 |