How to tackle red mite infestation in hens

Getting to grips with red mite has never been more important with the welfare challenge and associated economic costs on the increase, and the number of effective treatments on the wane.

Addressing the BEMB Trust’s workshop, free-range egg producer and chairman of the British Egg Association, Jeff Vergerson, outlined the existing problems associated with red mite infestations.

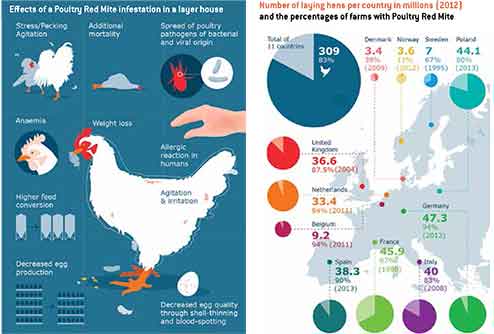

In terms of welfare, hens suffered considerably from night-time attacks. The burden could be as high as 500,000 mites per hen, and these mites could consume up to 5% of the hen’s blood in a single night.

“We always struggle to keep the birds performing well,” said Mr Vergerson. “They lose performance and can become anaemic.”

Most recent survey work showed that 60-65% of all flocks in the EU were affected with red mite, and egg losses of up to 25% had been recorded, as well as reduced feed intake and increased mortality.

Egg quality could also suffer, with pale yolks and delicate shells. Increased numbers of floor eggs were a common sign of red mite infestation, and in extreme cases, eggs on the way to the packing station could be stained with mites and blood.

The stress caused to the birds could also leave them more susceptible to disease, while the red mites themselves were recognised as vectors for numerous pathogens, such as Salmonella enteriditis, fowl typhoid, E coli and avian leucosis.

There was obviously a significant economic cost associated with the problem. While there had been no recent work on this subject, one ADAS study had put the estimated annual cost at £3-4m, while another study put the cost throughout Europe at €130m.

All production systems were vulnerable, though wooden buildings provided mites with more harbouring opportunities. But even newer sheds, with metal and plastic constructions, have plenty of angles and corners for populations of red mites to develop.

Yet the opportunities for controlling red mites were becoming increasingly limited, said Mr Vergerson.

Options included physical removal, such as brushing, vacuuming and blow torching the buildings, and chemical treatments of both houses and live birds.

Abrasive and desiccant products were available, which sought to damage the mite’s exoskeleton, while plant derived products could be used to kill or repel mites. Vaccines were another option, but not in the short term.

With mites capable of surviving up to nine months without a feed, and mite eggs especially resistant to chemical attack, achieving 100% clearance was almost impossible, and population growth rates were rapid. “The mites are so small, they can avoid just about everything we throw at them,” said Mr Vergerson.

Discussion

Getting rid of red mites is an impossible dream, so the emphasis must be on getting infestation rates down to an acceptable level.

Increasing biosecurity in the egg laying sector was seen as an important measure to try and stop red mites entering a shed in the first place, including such things as proper boot dipping, overall changes and cleanliness of the transport modules.

Standards of biosecurity in some countries were believed to be generally lower in the egg sector than the broiler sector, though Spanish representative Maria del Mar Fernández said that was not the case in her country, where most producers ran cage units of over 100,000 birds.

Gareth Griffiths of Oaklands Farm Eggs believed that younger birds were less susceptible to red mite attack, and reported very few problems with chicks and pullets brought on to the farm.

But once they went into the laying sheds, the problems mounted, and this was exacerbated by the fact that red mite resistance to most of the limited control products available was increasing all the time.

This problem of resistance was noted by many of the experts present. They also agreed that the move to enriched colony cages in 2012 had made the problem worse, as these were harder to clean and the mites had additional harbouring points.

Monique Mul from Wageningen University in Holland said five years’ worth of data had shown that the more complex the housing system, the greater was the incidence of red mite and the more difficult it was to reduce them.

Some delegates believed free-range systems were worse for red mite, as the hens lived in dirtier conditions and had more contact with wild birds. But Swedish Egg and Poultry Association representative Magnus Goransson said red mites had not been found in birds’ nests around sheds, while Italian delegate Prof Antonio Camardo from Bari University said it was more an issue with urban pigeons.

A VIEW FROM ABROAD

Denmark

Use lots of water when applying chemical treatments for red mites and do the spraying at night. That was just some of the advice given by Charlotte Frantzen Bjerg, describing the situation with red mites in Denmark.

Ms Frantzen Bjerg explained that egg production was relatively small in her country, with just three million hens, of which 1.7 million were kept in enriched cages. But infestation rates were high, with 85% of flocks affected by red mite.

These levels had increased over the past five years, she added, as traditional barns, which accounted for 20% of Danish production, were converted into more modern aviaries, which made it easier for mites to survive and reproduce.

When it came to control, Ms Frantzen Bjerg said Danish farmers used Elector, Bye-Mite and Silica. “We had very good effect in the beginning with these, but then the mite became more and more resistant. So we need to have a mixture of treatments.”

She said it was important to give everything a good soaking – “use lots and lots of water” – and to spray systematically. Night-time spraying should also be considered, to catch the mites when they were out and about feeding.

Evidence also suggested that spraying at lower temperatures could be more effective. “We trialled Elector in two stables with cages and set a different temperature in each,” she said. “We had the very best results with the lowest temperatures.”

Italy

There is considerable confusion at producer level in Italy about the rate of infestation with red mites, and about the consequences.

Vito Mastrangelo from the Italian poultry association told the workshop that a recent survey of 58 laying farms in south-east Italy had found red mite populations in 74% of them. But only half the farmers were aware they had a problem, while 20% denied any knowledge of red mite at all.

“There was also a lot of confusion about what the consequences of red mites were,” he said. “Some 40% said there was no anaemia in birds, and that there was no influence on laying percentage, or on the quality of the shell.”

The incidence of red mite was highest in the summer, which was when producers treated for it. The most common method was with acaricides (74%), while about 20% of the producers also used diesel oil.

“Only two of the farmers did any treatment when the farm was empty,” said Mr Mastrangelo.

Red mite research – recent and ongoing

Royal Veterinary College – Prof Fiona Tomley

Various projects looking to develop a vaccine that could be administered to a hen as part of a coccidiosis treatment, containing an antigen that is harmful to red mite. Also developing mice strains for testing red mite antigens.

Northumbria University – Prof Olivier Sparagano

Ongoing research into antigens and novel products, including essential oils and their chemical components. Also investigating the use of red mite predators, such as beetles and predatory mites, and metabolism pathways to better understand resistance.

Moredun Research Institute – Dr Alasdair Nisbet

Two vaccine development programmes. First, looking at autogenous vaccines using Soluble Mite Extract producing antibodies to kill mites. 75% effective in trials and now taken on by a commercial partner. Second, developing a Recombinant Subunit Vaccine using gene sequencing to identify candidate molecules.

Newcastle University – Dr Jonathan Guy

Investigating plant-based acaricides, taking 50 essential oils and testing for toxicity against red mites. Thyme essential oil showed most promise, but problems with low residual toxicity. Project stalled in 2007, but fresh funding being sought.

Bristol University – Dr Gerald Coles

Research into effect of different lighting regimes. Giving hens four periods of 3.5 hours of light a day most effective against red mites. But contravenes regulations and DEFRA funding stopped.

Future work packages

The BEMB Trust workshop concluded by agreeing a number of work packages, designed to prioritise areas for further research, encourage information exchange throughout Europe and develop “best practice” advice for controlling red mite. It is also aiming to boost public awareness of the significance of the red mite threat, in order to open up more research funding.