Controlling poultry house ventilation

Equipment specialists the Draper Group held a recent workshop for broiler growers on the fundamentals of poultry ventilation. Philip Clarke went along to find out more

Controlling the climate inside a broiler house is an art form that can reap rich rewards if the poultry keeper gets it right, or cost a small fortune if he gets it wrong.

One of the greatest difficulties, according to Ian Griffin, business development manager with the Draper Group, is the vagaries of the British climate.

Most of the heating and ventilation equipment coming into the UK had not been designed for UK conditions, he told company clients attending the seminar near Gloucester.

“Our weather is very different to the Continental conditions found in places like Sweden, Holland or Germany,” he said. “Our winters are warmer and wetter, while our summers are cooler and wetter.

“But many agents fail to take this into account. They just sell you the kit, give you the brochure and leave you to get on with it.”

Mr Griffin said the starting point was to consider the aims of a poultry house ventilation system, and build it up from there.

| AIMS OF POULTRY HOUSE VENTILATION • Evenly distribute a sufficient supply of fresh air to the entire flock • Eliminate draughts for young chicks • Remove excess heat and moisture • Maintain an even ambient house temperature • Limit the accumulation of harmful gasses • Minimise dust • Provide oxygen for respiration • Keep litter dry and friable • Create cooling air flows for older birds in warm external conditions |

|---|

• Ammonia below 20ppm

• Carbon dioxide below 0.5%

• Humidity below 84%

• Dust levels below 1mg/sq m

The MVR would vary depending on the age, weight and stocking rate of the birds, though flow rates should also be adjusted to account for things like litter condition, external temperature and fan performance.

According to company director Paul Draper, stockmen should also pay attention to the maximum ventilation requirement – the amount of air exchange required by a mature flock in hot conditions in order to maintain control of temperature and humidity.

“Over-ventilation can be a problem too,” he said. “Birds seem to like it a bit stuffy, with not too much fresh air. Unfeathered birds hate cold drafts. Sometimes stockmen can overdo the ventilation as they push for dry litter, which can be detrimental to the birds’ performance.”

But perhaps the greatest skill when it came to ventilation was in understanding the laws of relative humidity.

“When heated, air expands and can hold more moisture,” explained Mr Griffin. “The moisture holding capacity of air doubles every time the air temperature is raised by 11C. This is used to remove moisture from the air in houses during cold weather.”

Mr Griffin said the relative humidity in the house should be around 60-70% for the first few days of brooding, reducing to 55-60% thereafter. “If it is too low at placement, the mucus membranes in the respiratory tract and the developing pulmonary and circulatory systems may be adversely affected, leading to problems later in life.”

But he also warned that getting relative humidity too high could lead to problems. Condensation would lead to wet litter, high ammonia and would attract chicks to the walls in search of water, leading to stunting.

While heating the shed would help remove excess moisture, it could lead to additional problems. For example, direct combustion heaters would use up 15.5 litres of fresh air to burn just 1 litre of propane, and in the process would generate three litres of CO2 and 1.5 litres on water.

“This requires that the shed is ventilated, to remove the CO2 and water, to maintain a healthy environment,” said Mr Griffin. “In the UK winter, this introduces outside, cold, moist air, which demands extra heating and further ventilation; it can become a vicious circle.”

According to Mr Draper, in winter producers tend to increase the heat and reduce the ventilation. “But this can lead to poor bird performance in the winter, as the noxious gasses this produces sink to the floor.”

One solution being advocated by the Draper Group is to use indirect heating, with the fresh air passed over hot water radiators serviced by an external boiler. While the capital costs are higher, there are significant savings in running costs, and the ventilation rate can be set to service the birds’ needs rather than compensate for the heaters.

Other options include under-floor heating and the use of heat exchangers, which use the warm, stale air extracted from the shed to pre-heat the cool fresh air going into the shed.

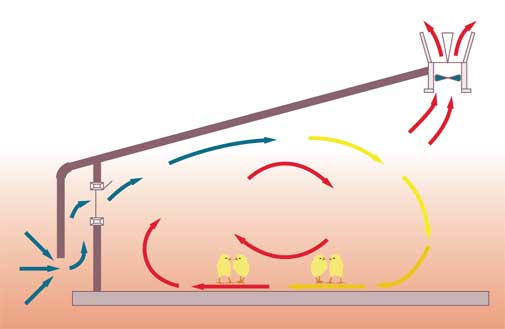

Recirculation of the warm air in the shed was crucial, added Mr Draper, to maximise bird comfort and evenness, to avoid heat loss through the roof and to ensure litter remains dry and friable. This was where having a smoke machine was critical, to visually reveal where the air flows were actually going. “In this context, there is no doubt that smoking is good news,” he said.

A question of balance

Getting the balance right by using extraction fans, circulation fans, air inlets, heaters and coolers was a real challenge, said Mr Draper.

The stockman should aim to keep the temperature steady and ensure adjustments are made gradually. There should be adequate ventilation to supply sufficient oxygen and remove excess moisture, dust and gasses. Any cold air entering the shed should not be allowed to drop directly on to the litter. “Attention to detail is everything.”

Mr Draper also stressed the importance of recording everything. This would help the stockman understand what was happening in each shed over time. “The worst thing that can happen is to get the job right, but not know why it is right so that you can replicate it in the next crop,” he said.

But whatever systems were available and whatever computer controls were linked together, there was no substitute for the skill and judgement of the individual stockman, said Mr Draper. “It’s so important to just sit down and watch the birds, to look for signs of over-ventilation or under-ventilation. I knew one guy who used to take a deckchair in so he could sit at bird level and observe what was going on.

“It also pays to kick the litter around, whenever you enter the shed. It can tell you a lot about the environment the birds are living in.”

SUMMER VENTILATION

Once the outside temperature warms up, the warm weather ventilation system takes over, extracting bad air and replacing it with fresh.

The rate of exchange is governed by the temperature and humidity inside the shed, moderated by the stockman’s judgement.

According to Mr Griffin, care needs to be taken not to introduce this system too soon. “Young birds, not yet fully feathered, may prefer the warm, damp conditions they have become used to rather than a sudden blast of cool, wet, outside air.”

The maximum ventilation rate would depend on the number of fans as well as the mass and age of the flock.

When choosing an extraction fan, Mr Griffin advised against buying one with a cheap Chinese motor that would underperform, and to beware of manufacturers’ performance curves which were measured in the US at 60Hz.

It was important to make sure louvres and flaps shut properly, and there should be proper safety guards that would not choke with feathers.

Inlet design was also crucial, especially the positioning. With the fans creating a negative pressure of 40Pa, air entering the building should have sufficient velocity to cover the full width of the shed.

As temperatures climbed above 25C in summer, it was important to deliver as much fresh air at bird height as possible. “Birds pant to keep themselves cool, so they must have fresh dry air, to allow them to sweat on the inside,” said Mr Draper.

The majority of birds died in hot weather as the sun went down, he explained, as the temperature dropped in the shed, humidity climbed from 60-80% and the birds struggled to evaporate excess water from their bodies.

Mr Draper said he was wary of some evaporative cooling systems which used spray to cool birds. They worked well on dry days, but on more humid days could lead to health problems.

“We would not recommend installing evaporative cooling in order to compensate for an inadequate ventilation system.”