The value of the dead pig: Benefit of post-mortems

© Tim Scrivener

© Tim Scrivener Should I ever lose my phone, the finder would probably be quite concerned if they looked through my photos.

Obviously, there are a few of my family and pets, but a considerable number show bits of dead pig – guts, lungs, liver, heart and so on.

The reason for this is that I see potential value in a dead pig.

See also: African swine fever threat: What farmers need to know

Although I hope that mortality on farm is as low as possible, if any death should occur, it is important to open the pig up to try and understand the cause.

If any flare-up of disease that occurs can be diagnosed and treated early, this will be good for pig welfare within the group and should, ultimately, reduce the amount of medication required for treatment.

Where possible, changes can be made that can reduce the risk of disease in the future, such as implementing a new vaccination protocol.

Glasser’s disease flare-up © Julia James and Larkmead Vets

So, what things might be seen? Recently on several farms, the practice has seen a spike in Glasser’s disease.

This is caused by the bacterium Glaesserella parasuis and can show classic post-mortem findings, including excessive fluid within the carcass.

In addition, everything in the abdomen, chest and joints can be stuck together with a yellow gelatinous, lacy fibrin.

This disease most commonly affects younger pigs (two to three months old) in acute, sporadic outbreaks, so a prompt diagnosis and treatment are essential.

Gut issues

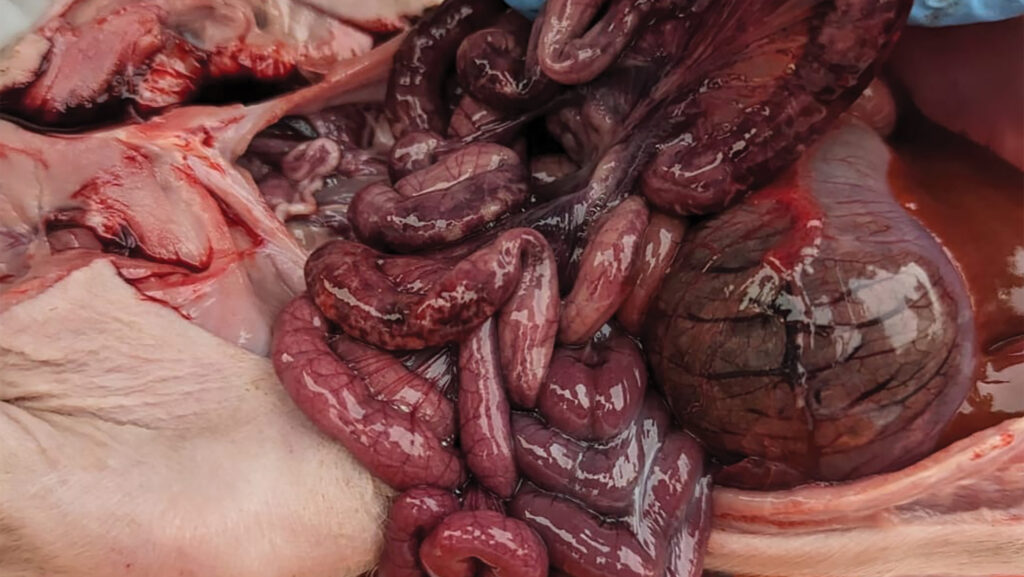

Gut issues can be seen in all ages of pigs, and post-mortem examination can often show inflamed loops of dark red intestines.

Laboratory testing should be used to confirm the cause of disease, so that appropriate treatment can be given when necessary.

Neonatal enteritis in a young piglet caused by clostridium pertfringens © Julia James and Larkmead Vets

Sudden death in a finisher pig can sometimes be caused by intestinal torsion.

Pigs are particularly susceptible to this, as their intestines are suspended within their abdomen by mesentery (a fold of membrane that attaches the intestine to the wall around the stomach area and holds it in place).

This is attached to only a short length on the underside of their spinal column, making it quite unstable especially if there is excessive gas in the guts.

Intestinal torsion in a finisher pig © Julia James and Larkmead Vets

Often it can be the best pig in the pen that is affected, possibly as a result of overeating.

Other factors, such as feed that is “off”, or an interruption in the feed supply, can also act as a trigger for torsion.

Over the past year or two, I have seen an increase in erysipelas on farm in growers and finishers.

The clinical signs often seen in the live pig are the classic diamond-shaped skin lesions and stiff pigs that are reluctant to get up.

In chronic cases, the bacteria can cause cauliflower lesions on the heart valves, and these are obvious to see on post-mortem.

It is especially important to remember that some diseases are zoonotic, so they can be transmitted between animals and humans.

Erysipelas is one of these.

Anyone carrying out a post-mortem should wear suitable protection, be trained in what they need to do and liaise with their vet about the findings.