New thinking needed on sire options

The choice of terminal sire is a hotly debated topic among suckled calf producers. Most have their preferences and can justify allegiance to a chosen breed, but all beef breeds have made significant growth rate improvements over the past 20 years.

Signet and Breedplan data show some breeds have increased their 400-day weights by well over 70kg, according to Simon Marsh, senior lecturer and beef cattle specialist at Harper Adams University College.

But because high growth rates are correlated to increased calf birth weights, there are, unfortunately, issues created with increased calving difficulties, says Mr Marsh. “Have we reached a point where our beef cattle have attained an optimum in terms of growth and do some breed societies now need to focus on other traits?” asks Mr Marsh, who cites the rise in cereal prices as a need to focus on the ability of some breeds to easily finish off forage.

A recent EBLEX survey of English suckler herds showed the Limousin to be the predominant terminal sire, accounting for 33% of bulls used, followed by the Charolais with 17%. Angus, Blonde and British Blue bulls were all at 11%, with Simmentals at 7%.

“The Charolais was once the predominant terminal sire breed used in suckler herds, but due to the breed’s calving difficulties over the past 20-30 years there’s been a switch to the easier-calving Limousin by some suckled calf producers,” says Mr Marsh.

“But there are now anecdotal comments that calving ease is becoming a problem with some Limousin bulls – a logical development in line with the breed’s significant increase in its 400-day weights over the last two decades.”

Charolais bulls are used exclusively at Simon Frost’s Hopping Farm on cows and bulling heifers – a choice based on the breed’s record of being the highest growth rate sire of any beef breed – and are considered ideal to complement the herd’s “fine-boned” Limousin x Holstein suckler cows.

Ease of calving

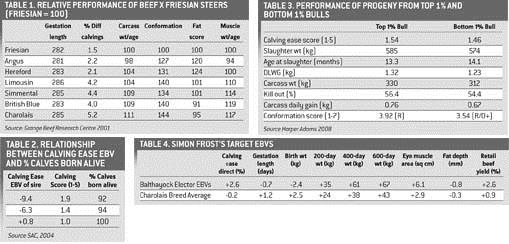

Table 1 showing the most recent figures from all the breeds reveals that, on average, Charolais’ have the highest incidence of calving difficulties. However, Mr Marsh states categorically that there is more variation within a breed than between all the major beef breeds.

“There are easy calving Charolais bulls as well as those that produce a high level of difficult calvings. It’s no understatement to say Mr Frost spends a considerable amount of time studying bull sale catalogues in search for ‘curve benders’ which are the easy calving bulls identified by EBVs but bulls that have very high growth rates and muscle area,” he says.

Ease of calving is a priority in suckler herd management so easy-care systems can be efficiently run using less labour. In a recent study by the Scottish Agricultural College, three Charolais bulls with varying degrees of calving ease EBVs were compared. Calving score was based on a scale from 1 (unassisted) to 5 (caesarian).

The most relevant statistic is produced by the bull with the positive calving ease score, which resulted in 100% of his calves born alive. Based on a 200-day weight of 280kg achieved by the calves sired by this bull, calves from the study’s difficult calving sire would need to be an average 24.3kg heavier to produce the same total calf weaning weight. This simple calculation ignores the potential issues of reduced fertility associated with cows that have endured calving difficulties.

Using the science of EBVs

“The beef industry must move forward and use the science of EBVs to enable breed improvement to progress,” says Mr Marsh. “Breed improvement is a long-term issue, but with high feed prices it’s even more imperative for suckler herds to produce well bred cattle sired by bulls with high indexes.”

In a recent trial at Harper Adams, dairy-bred calves by Limousin bulls – that were either in the top 1% or bottom 1% on Beef Value – were intensively finished.

The results found calves sired by the bull with the top 1% index smashed the EBLEX target for slaughter weight of continental-cross dairy-bred bulls with a weight of 585kg at 13.3 months, compared to the target of 570kg at 14 months old.

“The faster finishing and increased slaughter weight, as well as the improved carcass grade of the calves from the top 1% bull, is worth a phenomenal £116.24 a head at today’s beef and cereal prices. So, if each bull sires 200 calves it equates to a suckled calf producer being able to pay £23,248 more for the top 1% Index bull.”

For suckler producers to reap these financial rewards, the beef industry must move forward and adopt the science of EBVs, says Mr Marsh.

“Numerous studies have proved their value and the financial rewards are significant. The industry must change and move away from selecting bulls with fancy, masculine heads. A head has no value to the meat trade.”

He is equally adamant that the fascination with big back ends must stop. Although a bull’s EBVs might alter slightly over time, these are changes that occur as more performance data becomes available and hence improve the accuracy of his predicted performance.

“Pedigree breeders must be honest about recording calving ease. As more calving data becomes available on individual bulls, there will be an increase in the accuracy of Calving Ease EBVs and breeders who falsify data will be caught out. The minimum requirement is 50% accuracy for the Calving Ease EBV when selecting a bull unless he is a young bull from a breeder you can trust.”

How does Simon Frost use EBVs?

Mr Frost has faith in EBVs and achieves top 1% performance. His bull calves last year recorded an impressive daily carcass gain from birth to slaughter of 0.94kg.

Although he acknowledges making the first decision to buy a bull on its EBVs demands a “leap of faith”, he’s in no doubt the odds will always be stacked in favour of the bull producing superior progeny compared with a bull with no performance recording.

“It’s like throwing two dice. The dice are always consistently weighted for you and never against you when you’re using a bull bought on his EBV,” says Mr Frost.

“It’s easy to follow the crowd and buy bulls based on looks and pedigrees alone, but so many of these bulls prove to be a disappointment and don’t live up to their potential as sires. I know a lot of people still lack confidence about basing a purchase on EBVs, but in my experience it has had a massive impact on the profitability of the business.

“Talk to as many people as you can for advice – Ian Pritchard of SAC has been a tremendous help to us – and use the Breedplan information to get a real grasp of using EBV for bull selection,” says Mr Frost.

His recent bull purchases include Balthayock Clifford (Terminal Index +45) and Balthayock Elector (TI +44). Both are top 1% bulls and Elector was bought this February at Stirling.

Mr Frost’s parameters for the various EBVs that he looks for when buying a bull are as follows: Calving ease direct, gestation length, birth weight, 200, 400 and 600-day weights, eye muscle area, fat depth and retail beef yield.

Selecting bulls with above EBVs results in progeny with the potential for very high growth rates with U-grade carcasses. Last year 56 bull calves recorded a carcass weight of 438kg at 447 days (14.6 months) old, which is exceptional performance.

HABFF