Identify, treat and control BVD in your herd

The health of UK herds may be at increased risk from the more severe type 2 bovine viral diarrhoea (BVD) due to cattle imports from countries where this strain is more prevalent.

Of the two types of BVD – a disease that causes significant economic losses to the cattle industry – UK farmers have been tackling type 1 for more than 50 years.

See also: Tackle bovine viral diarrhoea in your herd

But greater awareness is needed of the potential to import type 2 infected cattle from Belgium, Germany, The Netherlands, Italy and also North America, where cases are more common.

Mike Kerby, partner at Delaware Veterinary Group, Castle Cary, Somerset says: “The worry is that open trade with mainland Europe, where there have been cases, and North America, where there is closer to a 50:50 type 1 and type 2 split, means farmers need to be aware of the potential disease risk.”

And while type 2 is so far relatively rare and few cases have been reported in the UK, it tends to cause far more severe signs and has a higher mortality rate than type 1, he adds.

BVD strains

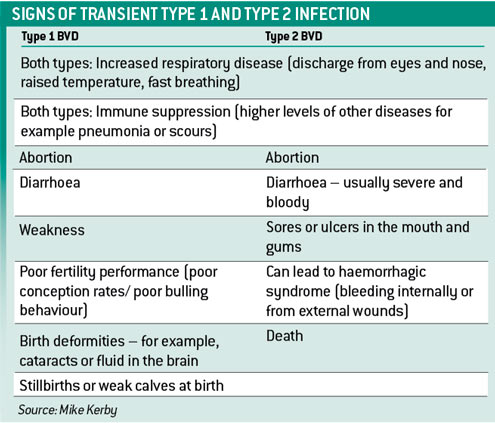

Mr Kerby explains how both types can show similar initial signs in transiently infected animals – which means any that have not been infected before and are challenged by the disease (see “Signs of transient type 1 and type 2 infection”, below).

“Similarities continue in as much as both cause immune suppression – where any other diseases can be far more severe and the body is less able to deal with them,” he adds.

Type 1 infections are generally mild and can often go undiagnosed as BVD, whereas type 2 can lead on to bleeding from wounds or internal organs and other more severe clinical signs such as bloody diarrhoea.

What are persistently infected animals?

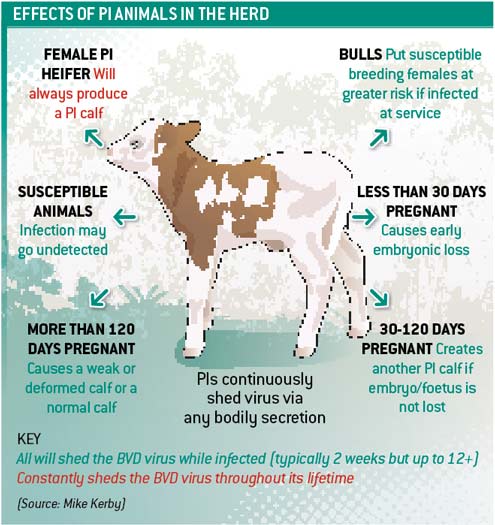

As transient BVD infections can pass unnoticed, farmers may be unaware of the potentially detrimental effects of BVD to unborn calves, should in-calf heifers or cows become infected with type 1 or 2 between days 18 and 120 of their pregnancy.

They will pass the disease into the foetus, as it is yet to develop its own immune system. If the calf survives, its body thinks the virus is part of itself so does not make antibodies against it, explains Mr Kerby.

If the animal is born with the virus it is known as persistently infected, or PI. These animals never make BVD antibodies, but shed high levels of the virus, spreading BVD throughout their lives. PIs can look normal, but may not thrive as well as others.

“Once infected inside the mother, the die is cast, there is nothing that can be done. PIs are the biggest source of infection to others,” he adds.

PIs with type 1 BVD can end up with mucosal disease if the virus mutates or the animal is infected with a cell-damaging strain.

“Mucosal disease is mostly seen between 15-24 months old. Signs include severe ulcers or erosions in the mouth and sometimes on the coronet [piece of skin above the hoofwall].

“There is rapid weight loss and uncontrollable diarrhoea. Animals die within a few days,” he says.

The severe form of transient type 2 BVD also shows the same signs as mucosal disease, so farmers may mistake a type 1 PI with mucosal disease for a transient type 2 infection.

According to Mr Kerby, the single biggest difference between herds that are BVD-free and those with PIs are borders. He strongly advises farmers not to have cattle in adjacent fields to neighbouring farms.

While a PI may look normal, visible signs of PIs with types 1 and 2 BVD include:

- Stunted growth

- Wasting

- Diarrhoea

- Mucosal disease.

Spread and control

BVD is highly infectious and can be spread by direct and indirect contact. Risks are particularly high at UK markets, where animals of unknown BVD status may be in close proximity with one another.

Cattle on neighbouring farms may also make contact if field boundary fencing is inadequate. Contaminated equipment, visitors, slurry and biting insects all pose further risk of indirect spread.

Mr Kerby says as type 2 is not yet endemic in this country, most animals are potentially susceptible as they have no antibodies against the virus.

“If farmers are importing animals with transient type 2, they will produce lots of virus and if they come into contact with other herds you can see how it would spread quite quickly,” he adds.

Those unaware of the different strains of BVD may mistake a cow that’s puffing, off its food and producing less milk as having pneumonia, says Mr Kerby.

By the time bloody diarrhoea develops, it’s too late and type 2 could have spread.

There is no specific treatment for BVD and routine testing does not differentiate the types, so veterinary medicines are used to relieve symptoms or specific concurrent disease challenges.

“There are no immune stimulant drugs licensed in cattle, but evidence has shown a double dose of levimasole may help immune suppressed animals,” adds Mr Kerby.

Vaccinations are available for type 1. The antibodies produced as a result may last six to 14 months so regular boosters are vital.

Breeding females should be vaccinated before mating to avoid transient infection in early pregnancy as this is when they are most at risk of developing a PI, he explains.

Calf vaccinations should be planned with your vet as timing depends on the management system in place and herd health status. The main aim is to protect beef and dairy heifer

calves throughout their rearing period.

“Once an animal has been infected ‘from the field’ with type 1 virus, they do get several years of immunity with a reasonable level of antibodies,” he says.

Four steps to eradication

- Plan. Get an understanding of the disease from your vet and set herd targets – for example, improved fertility or BVD-free status.

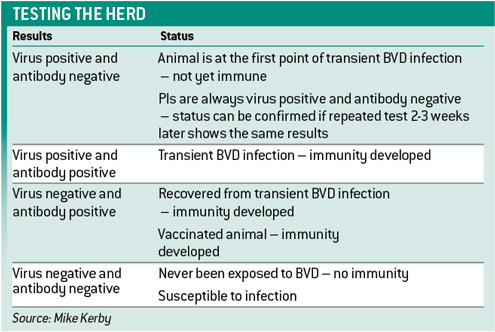

- Investigate. Find out your herd/individual animal status and decide on vaccination or control methods. For example:

-Blood sample for virus or antibodies

-Tag and test for virus by taking a small tissue sample from the ear (useful for calves)

-Bulk milk test for antibodies or PCR test milk for virus covering up to 300 animals, but not dry cows or heifers.

- Control. Act swiftly and decisively to control BVD:

-Identify the PIs and cull them out

-Vaccinate heifers and cows for immunity before service

-Run a closed herd or only buy from known-status sellers

-Quarantine and test, if it has not been done recently, before mixing

-Minimum of 3m, double-fenced borders; avoid grazing adjacent fields to neighbouring cattle – keep one field distance

-Use some form of biting insect control

-Improve biosecurity

-Vaccinate calves for immunity during rearing.

- Monitor. Whether you test for virus, antibodies or both and how often you test depends on which control methods are in use. For example, if you haven’t vaccinated and animals test positive for antibodies, you know BVD has got into your herd.

A Farmers Weekly campaign to help tackle BVD infection, in association with BVD-Free England and Beating BVD.